PORTLAND, MULTNOMAH COUNTY; 1880s, 1890s, 1900s:

In 1880s Portland, at least one mayor paid to play

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

CHAPMAN’S ADMISSION WAS pretty much the high point of blatant corruption in Portland City Hall in the 19th Century. But he certainly wasn’t the last colorful character in the office. Sylvester Pennoyer (1896-1898) and George Williams (1902-1904) both were established politicians with national reputations who more or less retired to the job in their golden years. Pennoyer was most famous for feuding with sitting U.S. Presidents (“Washington: I will attend to my business. Let the president attend to his.”). In an ironic twist, it fell to him to emcee the dedication of Portland’s then-new Bull Run water-supply system, the construction of which he had opposed as governor. Virtually the entire city was looking forward to the change, as the city’s water had always been taken directly out of the Willamette River; it was already cloudy and nasty, and was getting more so as more and more people lived (and — ahem — flushed) upstream at Oregon City, Salem, and beyond. If forced to be frank, Pennoyer would no doubt have admitted he’d been wrong to oppose and try to block the Bull Run project. But admitting he was wrong was not a thing Sylvester Pennoyer did — ever. So as he raised the glass and took a drink from it, he went for humor instead: “No flavor. No body,” he grumbled irascibly. “Give me the old Willamette.”

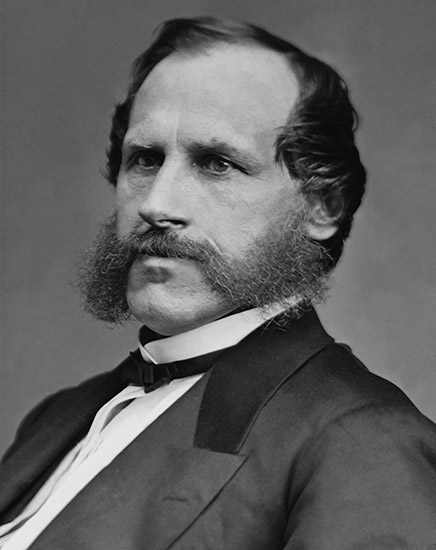

GEORGE H. WILLIAMS WAS commonly called “Wide Open Williams” for his permissive attitude on vice. But he had probably the most impressive political resume of any Oregonian in the 1800s. In fact, Williams was probably the most interesting public figure in 1800s Oregon. Just before the Civil War, when still a Democrat, he had been instrumental in the creation of Oregon's state constitution, with its notorious race-exclusion clause; but, as the chief justice of the Oregon Territory's top court, he'd also been instrumental in establishing free blacks' property rights when he ruled in favor of black plaintiff Letitia Carson, restoring her property after it was stolen under color of law by a wealthy white neighbor (here's that story). After the war, he served as U.S. attorney general under President U.S. Grant. Williams was in charge of the Justice Department during Reconstruction, and prosecuted the Ku Klux Klan with commendable vigor throughout the 1872 election season – just long enough to ensure that African American votes were not suppressed (the black voters, of course, went for Grant almost to a man). Once his president was safely re-elected, though, he lost interest in keeping the Klan down. The next year, Williams had been nominated chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court — but his wife, Kate Ann, had made so many enemies among the wives of the U.S. senators in Washington, D.C., that they undertook a highly effective and coordinated “pillow-talk lobbying effort” that resulted in her husband being forced to decline the nomination and, in 1875, to slink back home to Portland with his tail between his legs. (More on that story here.) Kate Ann had then further added to the dark lustre of her reputation by becoming the founder-prophetess of a starvation cult called “Truth,” which met in her living room. She and at least one of her followers died of starvation, in 1894, by following its strictures. (More on that here.) As mayor, Williams was only slightly controversial. He was indicted, along with police chief Charles H. Hunt, for failure to enforce gambling laws in 1904; acquitted, he served out the remainder of his term and, at the ripe old age of 84, retired from public service for real. In next week’s column, we’ll talk about the 20th century, and especially about the two mayors who probably did the most to shape postwar Portland: Dorothy McCullough Lee and Terry Schrunk.

|

Background image is an aerial postcard view of Haystack Rock and Cannon Beach, from a postcard printed circa 1950.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2021 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.