PORTLAND, MULTNOMAH COUNTY; 1874:

‘Crusade’ collapsed when leaders got too preachy

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

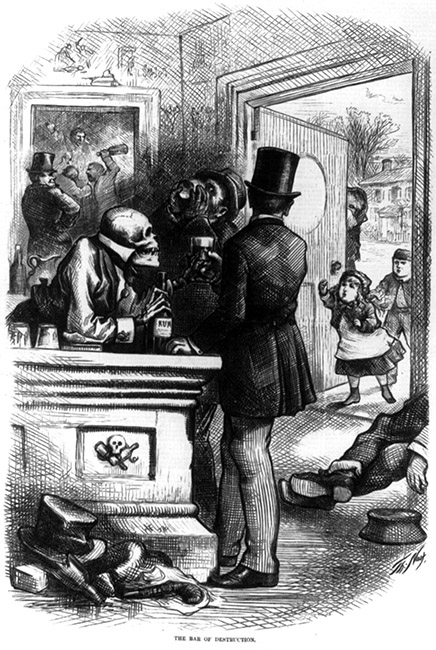

A full slate of Temperance candidates was drafted and put forward for the upcoming election. Most Portlanders looked upon them with some favor, thanks to the copious goodwill generated by the crusading ladies. Then, on the day of the election in early July, a little publication was distributed all over Portland, titled “The Voters’ Book of Remembrance” — although it was not actually a book, but rather a half-sheet flyer. This innocuously titled circular was unsigned, but everyone assumed the League had published it, as of course it had; a traveling troublemaker-preacher named A.C. Edmunds was responsible for it, and had sent it out on their behalf. (More about A.C. Edmunds — lots more — here.) But if the saloonkeepers had put it out as a dirty campaign trick, they would have been very pleased with the result. The “Voters’ Book of Remembrance” put the entire city into a cold fury. Its language doesn’t sound too bad to the modern ear, but in 1874 it was outrageously unsubtle — and, what was worse, insulting. “Voters of Portland, the Book of Remembrance is this day opened, and you are called upon to choose ‘whom ye will serve,’” it starts out. “On one hand are found prostitutes, gamblers, rumsellers, whiskey topers, beer guzzlers, wine bibbers, rum suckers, hoodlums, loafers and ungodly men. On the other hand are found Christian wives, mothers, sisters and daughters of the good people of Portland. You cannot serve two masters. You must be numbered with one or the other. Whom will ye choose?” In other words, as historian Clark puts it, “any citizen low enough to vote against the Temperance candidates was a supporter of Sin, an un-American scoundrel, and an arch-foe of Home and Mother.” Remember, this was a pre-Suffrage election, so it was to be decided by men. Most men, in 1874, had at one time or another participated in saloon culture — some of them on a daily basis, others very occasionally. And although it was a particularly hard-drinking age, not every Portland man was a souse. Responsible drinkers have always been with us, and in 1874, as in most times, they represented a great majority of the male population. Now here came these Temperance scolds to tell Joe Sixpack-A-Week that he must either dry out completely and join the “crusade” or be numbered with hookers, swindlers, loafers, thugs, day-drinkers, and “ungodly men.” No sale, Reverend. The temperance candidates, who 24 hours before the election had looked like shoo-ins, were trounced. The Women’s Temperance Prayer League vanished, its constituents slinking away from the public-relations fiasco that someone had signed their name to. It was replaced by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which lasted for years but never had the same kind of influence. Ironically, probably the biggest loser in the whole fiasco was the woman whose newspaper had catalyzed the whole movement. Abigail Scott Duniway now got to watch her worst fears become reality: The women’s suffrage movement became irrevocably tied to the temperance movement in most Portlanders’ minds, and the temperance movement was now painted in the popular imagination as preachy, self-righteous, meddlesome and generally insufferable. It would take decades for this association to dissipate. Speaking of dissipation, let’s turn back to Walter Moffett for a moment. He started wasting away just a few months after the election. Then he sold his saloons and sailed off to the South Seas — a relatively unremarkable thing to do today, but a fairly odd action for a middle-aged married man of property to take in 1875; in that era of small, vulnerable sailing ships, sketchy navigation and nonexistent weather forecasting, people didn’t go to sea unless they had to. In any case, Moffett died en route. His cause of death was officially something else, but it’s at least possible that he was suffering through the final stages of syphilis, which in that era caused many a middle-aged man to become mentally unhinged and then die early. Certainly that would explain why a man who had clearly once had enough good judgment to build several successful businesses suddenly thought it would be OK to throw firecrackers at praying ladies on the street and call them “damned whores.” But, of course, we can’t ever really know.

|

Background image is a hand-tinted linen postcard view of Three Sisters from Scott Lake, circa 1920.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2021 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.