PORTLAND, MULTNOMAH COUNTY; 1874:

Portland’s “Temperance War of ’74”: The backstory

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

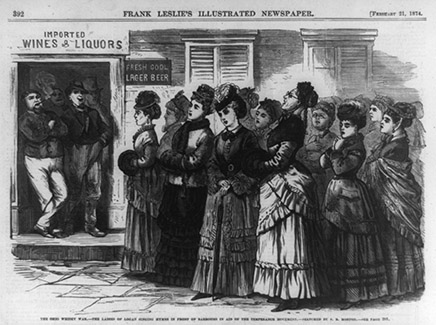

There they decided, as the Portland Bulletin’s reporter put it, to “go forth and beard the lion in his den” — by going out two by two, as Jesus sent forth his disciples, to hold their temperance-church services in the saloons themselves. A few of the more conservative ladies thought that was too much, and when the decision was made to do this, they dropped out. But there remained a total of 13 game sisters who were ready to go out there and change the world. And so it was that on March 23, 1874, a team of fired-up ladies streamed out of the church and, in groups of two and three, fanned out across Portland.

For a Victorian-era lady, this was nowhere near as easy as it sounds to the modern ear. Laura Francis Kelly, one of the temperance crusaders, wrote a hand-written account of how it went: “Can you imagine what it would be to go into a saloon to pray? Then you can imagine how we felt. I cannot tell you. “The saloon keeper received us cordially, ushering us into the card-room. As the song rose from trembling hearts: ‘Holy Spirit, faithful guide, Ever near the Christian’s side,’ etc., the bar-room quickly filled with young men to whom the barkeeper freely dispensed his liquors. As we knelt in prayer, the clink of glasses well nigh drowned the petitions that rose from trembling lips. When the short service was over, the bar keeper invited us very pleasantly to ‘come again.’ Oh! how we hastened back to church and kindred spirits! But the pastor, George W. Izer, met us with, ‘Back so soon? Did you visit only one saloon?’ Then we saw what was before us.” At the end of the day, they were exhausted and demoralized. True, the ladies were treated courteously everywhere (with, the Bulletin sniffed, the notable exception of “the proprietress of a low doggery on Second Street” — and one other place, which we’ll talk about next week). But as crusader Kelly mentioned, saloons were noisy places. A pair of frightened ladies standing close together in a corner singing hymns was easily ignored. In the pubs where they were not ignored, they were treated as objects of curiosity, as if a circus act was visiting the saloon. Few if any of the men in the saloon even bothered to listen to their message, and more than one liquored-up wag made fun of them, pretending showily to be convinced and signing a fake name to the temperance pledge. Back in the church, the ladies prayed for strength and then went home for the night.

The ladies fortified themselves with a lengthy prayer service, then poured forth once again from the church into the mean streets of Stumptown’s saloon district. Today they descended upon the Mount Hood Saloon, owned by a chap named Thomas Shartle; he graciously let them in and gave them the run of the place. Shartle did not, however, turn off the taps, and was probably glad he did not. If two Victorian ladies in a saloon was a little like a circus act, thirteen of them was more like the whole circus. People poured into the Mount Hood. On the surface, it looked like a repeat of the previous day’s disaster, only on a bigger scale. Mr. Shartle did a brisk trade. The ladies got the same faux-hearty “best of luck to you, God bless you, here’s to ya” response from the same saloon bums, and fielded the same fake signatures on the temperance pledge. But this time, the “clink of glasses” was powerless to drown out their voices as they sang. There were, after all, a baker’s dozen of them. They were too large a presence to ignore. The ladies moved on, going downmarket a bit and visiting a rum house called the Evening Call. Again, they brought the proprietor plenty of business and left with very few legitimate pledges. Back at the church, the ladies learned that word had gotten around the saloons that their presence represented a large business boom. One saloon owner actually sent them an invitation to come to his place, which — to his delight — they did the next day. But the sense of demoralization was now utterly gone. The ladies knew they were onto something. If some people were laughing at them, at least they were now being heard; their seed might be falling on stony ground, but at least it was reaching the ground and not being drowned out by the clink of glassware the instant it was thrown. They started going out every day, each day to a different saloon. And slowly, things started to change. We’ll talk about that change — and about the one saloon owner whose bellicose resistance to the ladies’ missionary efforts caused riots on the city streets — in Part Two of this four-part series.

|

Background image is a hand-tinted linen postcard view of Three Sisters from Scott Lake, circa 1920.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2021 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.