PORTLAND, MULTNOMAH COUNTY; 1874:

Stubborn saloonkeeper refused to play nice

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

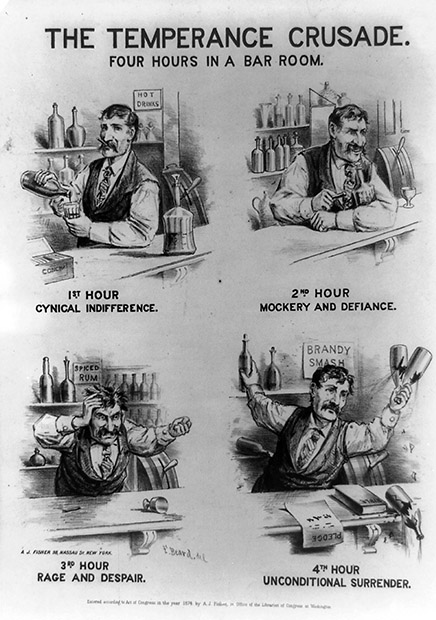

“‘Walter Moffett!’ she exclaimed. ‘Can this be Walter Moffett? Why, Walter Moffett, I used to know you; and I prayed with your wife for your safety when you were at sea years ago!’ “‘I don’t want any of your damn prayers; I want you to get out of this and stay out; that’s all I want of you. I don’t keep a whorehouse!’” Well then. These are words that even today would earn a man a lusty punch on the mazzard from pretty much anyone in a position to deliver one, male or female. The fact that Moffett didn’t get one on the spot can probably be chalked up to the utter improbability of his behavior, which was so far out of line with Victorian-era norms of how respectable women were supposed to be treated that the ladies were too flabbergasted to do anything but make their way back to the Taylor Street church and tell their comrades-in-arms what had happened. Their story galvanized the congregation there. Outraged and furious, they immediately moved Moffett's name to the top of their target list. For the next week and a half they tried to wear down his defenses by putting in daily appearances at his saloon — requesting entry, being denied and moving on. Finally, on the last day of March, they changed tactics. After being denied entry as usual, they lined up on the sidewalk and launched their prayer service right there, outside the door. Moffett’s response was almost as tone-deaf as his previous one had been: He emerged from his saloon wearing spectacles and holding himself with prim dignity, a copy of the Holy Bible in one hand. From this he proceeded to read a selection of passages which, taken out of context, sounded wildly offensive. (The only one of these specifically mentioned by the crusaders — the only one I could find in the Oregon Historical Society's records on the event, at any rate — is Deuteronomy 23:1, which reads, “He that is wounded in the stones, or hath his privy member cut off, shall not enter into the congregation of the Lord.”) The ladies sang louder to drown him out. Moffett increased his own volume until he was actually shouting. This went on for some time, attracting — as you can imagine — a healthy crowd of spectators. Finally, the ladies moved on. But before they left, one of them tearfully asked Moffett why he was behaving like this. His bellicose response was that he minded his own business and expected others to mind theirs, and he called the crusaders hypocrites.

THAT EVENING, THE ladies discussed Moffett at great length. Was he simply incorrigible, a waste of their time? Should they simply leave him on his road to hell and focus their attention on more salvageable souls? Or — or was his bizarre, erratic and offensive behavior a subtle call for help? Strange as it sounds, the “call for help” theory was the one that prevailed. Some of the ladies argued that his strange behavior must stem from an uneasy conscience, and that meant he was not beyond the reach of salvation. What Brother Moffett needed right now was not to be abandoned to his depravities and to the blandishments of Satan, but rather to feel the tough, brave love of his true friends, who would be there to support his struggle for righteousness no matter how viciously he tried in his self-destructive, demonic madness to drive them away. Looked at that way, leaving Walter Moffett alone would be a seriously sinful and selfish act, and one the ladies figured they’d be called to account for on Judgment Day. No, poor Brother Moffett would continue to receive his special treatment, along with earnest and loving prayers for his salvation, whether he wanted them or not. In other words, Moffett’s behavior had not only failed to persuade the ladies to leave him alone, it had put the full force of divine authority behind a mandate to continue pestering him. And the poor dolt clearly had no idea what he had done. We’ll talk about what this continuing attention would lead to in next week’s column.

|

Background image is a hand-tinted linen postcard view of Three Sisters from Scott Lake, circa 1920.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2021 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.