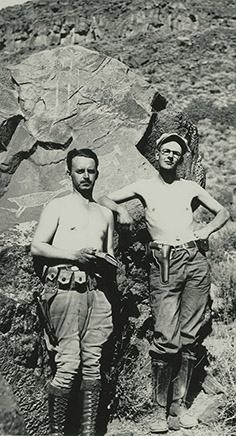

FORT ROCK, LAKE COUNTY; 1930s:

Cressman was Oregon’s real-life Indiana Jones

By Finn J.D. John

|

In the course of doing this, Cressman gleaned an understanding of the cultures of “ancient Oregonians” — an understanding that formed into a theory that put him at odds with the conventional wisdom of nearly every other scientist at the time. Essentially, every archaeologist but Cressman was convinced that the Clovis People, an ancient culture named after a New Mexico town where their artifacts were first discovered, had been the first humans to ever live in North America. This “Clovis First” theory held that until a hundred centuries ago or so, there had been a “land bridge” connecting Siberia with Alaska, and that the Clovis people had crossed over it into Alaska some 13,000 years ago, arriving in an empty virgin continent. According to the theory, their slow spread through North America had only reached what is now Oregon just two or three thousand years ago. Cressman didn’t buy it. No way, Cressman said, were the artifacts he was finding out there young enough to be Clovis stuff. And he was not shy about sharing that theory, which made him something of a pariah in archaeology circles. The interesting thing about Cressman was that, in an age in which scientists tended to stay in their lanes — paleontologists sticking to looking for bones, geologists sticking to rocks, anthropologists studying native cultures, biologists studying pollen and tree ring evidence, all mostly in isolation from one another — Cressman made a point of reaching out across intellectual silos and making connections with people studying other things. In this way, he was able to put together pieces of evidence that less eclectic archaeologists would never see. Nowhere did this approach serve him better than with the legends and artistic traditions he learned about from his Indian friends, and the insights from geologists like Stafford that helped him estimate rough dates for his finds. And, this is kind of the point at which the comparison with Indiana Jones breaks down. Grabbing a golden idol off of its pedestal where it has sat for thousands of years and hustling it off to a display case in a sterile room in the Mother Country without so much as a photograph taken — Cressman would have considered that an act of cultural vandalism. Stripped of its context, an idol — or a flint arrowhead, or a pair of sage-bark sandals — loses its ability to tell its story: how it was used, who made it and when, what the environment was like when it was made, what its artistic style reveals about the movement of ancient peoples across the land. Basically, Luther Cressman was doing 21st-century archaeology in the late 1930s. And the academic (and sometimes pseudoacademic) artifact hunters of the day didn’t all appreciate the insights he was gleaning from that “meta-data” that he was being so careful to preserve.

Luther Cressman inspects an Indian basket from a collection at the UO Museum of Natural History in 1937, when the museum was still located on the second floor of Condon Hall. The museum, which Cressman founded, has moved to its own building and has been renamed Museum of Natural and Cultural History. (Image: UO Libraries)In one of those caves, he made the first of several discoveries of the sagebrush sandals that would make his reputation. He found, in excavations, that he could roughly date his finds by recording whether they were buried above or below the layer of ash from the eruption of Mt. Mazama, the ancient supervolcano that exploded and created Crater Lake. At the time nobody knew exactly how old Crater Lake was; but, there would come a time when researchers would learn it was more than 7,500 years ago — proving Cressman had been right to be skeptical of the Clovis-first theory. Below that layer of ash, in an overhang known as Cow Cave — now called Fort Rock Cave — he found sandals as well as the butchered bones of Pleistocene animals that were known to have died out more than 10,000 years ago. Ever the conscienscious fieldworker, Cressman treated every square millimeter of the sandals he found with a preservative solution. A few years later, after the technology of radiocarbon dating was developed, he was doubtless vigorously kicking himself for doing this. None of the sandals he had pickled in preservative could be dated. Luckily, an amateur artifact collector had dug some sandals out while Cressman wasn’t looking. Cressman was able to get hold of them, and sent them to be radiocarbon dated. They proved him right. They dated back over 10,000 years. The scientific community did not give up its “Clovis first” theory easily, but over the years they have by and large been forced to concede that Cressman was right and they were wrong. That was especially true after the early 2000s, when UO researcher Dennis Jenkins recovered some coprolites — dried or fossilized human feces — that dated to 14,500 years ago. There were some voices in the scientific community that clung to the Clovis theory for a few years after that, claiming the results of Jenkins’ coprolites must have been an error introduced by careless researchers. But such protestations had the distinct whiff of desperation to them. After all, where were these allegedly careless researchers going to be able to find 14,500-year-old DNA samples to contaminate the dig with? The result is that a new scientific consensus has developed, and anyone who still thinks Cressman was wrong has been left behind, yelling at clouds. You can actually see some of the sandals on display at the Klamath County Museum in Klamath Falls, by the way. Most of them are on display at the Museum of Natural and Cultural History at the University of Oregon, though.

There is just one kind of unsatisfying aspect of Cressman’s story, though. Although Margaret Mead was one of the most important anthropologists in the history of anthropology, if not the most important, it does seem a little unfair that the most common takeaway from the story of her ex-husband’s life and career is still the relatively insignificant fact that he was once married to her. But then, that’s a familiar story, isn’t it? From Ada Lovelace to Zelda Fitzgerald, from Alma Mahler to Marcia Lucas (and let’s not forget Dorothy “Mrs. Luther Cressman” Loch!), history is full of great women who are remembered more for who they were married to than what they accomplished. And, of course, what’s sauce for the goose is always sauce for the gander, right?

|