LAKE OSWEGO, CLACKAMAS COUNTY; 1900s:

Decade-long dam dispute resolved with dynamite

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

From the neighbors’ perspective, the company had offered them a deal which it had ignored utterly, reneging on every clause at the first opportunity. As a result, they had, they felt, literally had land taken away from them without compensation. The Oregon Iron and Steel Co. felt similarly hard-pressed, because the canal it had built between Sucker Lake and the river was only navigable at higher water levels. Although they no longer needed to navigate on it, if they allowed the canal to become unnavigable, the law would force them to abandon their water rights there. So the company didn’t budge, and off everyone went to court.

AT FIRST THE farmers met with little success in court. This probably wasn’t a huge surprise; Portland plutocrats William M. Ladd, Simeon G. Reed, and Henry Villard were among the owners and executives of the Oregon Iron and Steel Co., so taking the company on was like declaring war on all the political and business elites of the whole Portland Metro area. Three farmers filed lawsuits demanding a total of $22,500 in damages. All three suits were dismissed.

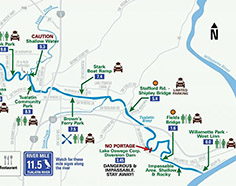

The Tualatin Riverkeepers’ recreational map of the Tualatin River Trail shows the once-controversial dam in the lower right (labeled “NO PORTAGE). The Lake Oswego Canal can be seen a few miles upriver from it, around River Mile 6.5. (Image: City of Tualatin) (Click image to enlarge, or click here for a PDF copy of the full brochure)Finally, in 1897, farmer August Krause filed another lawsuit. In it, rather than asking for compensatory damages, he sued for specific performance — asking the court to order the dam removed. It did, and ordered the Clackamas County Sheriff to tear out half of the dam. The company appealed immediately, and over the next several years the suit worked its way up to the Oregon Supreme Court, which ratified the decision. But only then was it discovered that the trial court had goofed up its order. The court had ordered the sheriff to proceed with “removing all but the upper 24 inches of the dam.” Well, this obviously put the laws of Oregon into direct conflict with the laws of physics. It also was very unclear what the court had intended to order: Remove the top 24 inches, leaving six feet of impoundment? Leave the bottom 24 inches, leaving two feet? Quite sensibly, the sheriff refused to proceed until he had better orders. So the whole thing started working its way back up through the legal chain of courts all over again, with the wording corrected this time. But late in the summer of 1906, ten years after the court had ordered the dam removed, some of the neighbors apparently decided to take matters directly in hand. Boom!

TODAY, ALL THAT’S left of the dam is the foundation part, which the river pours over in a great sheet of water to form one of those low-head dams colloquially known as “drowning machines” because of the way they pin unwary swimmers underwater in a great washing-machine-like swirl just below the downstream side. There’s no access to portage around it and it’s extremely unsafe to try to cross it, so it effectively functions as a block on the river. The Oswego Canal is still there, although it’s been many years since it was actually used for commerce. Today its main purpose is to bring fresh water in from the Tualatin River to augment the relative trickle from Sucker Creek, to keep the lake full and fresh. In February of 1941 Oregon Iron and Steel Co. gifted the lake, along with the canal and dam, to the 450 property owners in the city of Lake Oswego. Today everything is owned and maintained by the Lake Oswego Corporation, the private corporation created and owned by those property owners to hold and maintain it. Every few years a legal fight flares up over whether or not out-of-towners are allowed to swim and play in the lake; but the controversy over the dam has been mostly forgotten.

|