SALEM, MARION COUNTY; 1900s:

The bloody manhunt for ‘king of western outlaws’

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

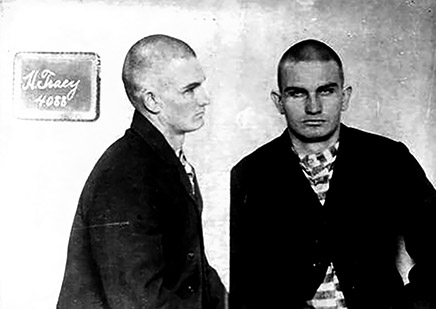

Posses were on their track almost immediately, of course, and bloodhounds were brought in from Walla Walla; but Tracy circled around and mixed his scent with that of the posse, and the dogs lost his trail. The governor offered a reward, then doubled it. As the weeks went by the reward was raised until it was $8,000, alive or dead. That’s nearly $300,000 in modern currency — an enormous bounty. This inspired dozens of ad-hoc packs of citizens grab a shotgun and a flask of whiskey, posse up, and join the hunt. The result was a chaotic landscape of heavily-armed drunks looking hopefully over every backyard fence for signs of Tracy and Merrill. “The whole damned country was full of militia, and many of the boys were potted,” Detective Joe Day of the Portland Police Department told writer Stewart Holbrook many years later. “They shot at everything, and Clark and Cowlitz counties sounded like the Spanish American War all over again. It was the most dangerous place I was ever in.” These boozy posses may have made the countryside dangerous for everyone, but they would have been no match for a professional killer like Tracy. Even stone-sober law-enforcement professionals had trouble on the few occasions when they caught up with him that summer. Tracy wasn’t long in Oregon. On June 16 he and Merrill held up three men on the south bank of the Columbia River in Portland and made them row them across to Washington. Newspaper readers then got to follow their progress by the reports of farmers and homeowners whom the two desperados “visited.” The outlaws would approach them with guns out, “request” dinner, make some small talk, requisition some supplies, and be on their way. One such home-owner reported, on July 3, that Tracy had appeared alone, and told him that he had killed David Merrill. “I was tired of him anyhow,” Tracy said, according to this citizen. Tracy had said he was headed for Hole-in-the-Wall Pass; but for some reason, he didn’t seem in too big a hurry to get there. After reaching Washington, his trail really meandered. He spent months lurking around the Seattle area, hijacked another boat to get to Bainbridge Island, came back, forced a farmer to buy him some fresh ammunition and a new revolver, and even kidnapped a Swedish farmhand as a personal servant for a few days. But by the end of the month, Tracy seems to have decided it was time to go to ground, and he left Seattle headed east. He resupplied from a homeowner in Palmer on July 23, and then was not heard from till Aug. 5, when a farmer near Odessa came home and found a note pinned to his door: “To Whom it May Concern,” it read. “Tell (Sheriff) Cudihee to take a tumble and let me alone or I will fix him plenty. I will be on my way to Wyoming. If your horses are good would swap with you. Thanks for a cool drink. —Tracy.” But, time was running out. The following day, Tracy found himself pinned down by rifle fire in a wheat field near Creston, and this time he couldn’t shoot his way out. After taking a bullet that cut a leg artery and another that broke his other leg, the dying bandit gave himself the coup de grace with his Colt .45, bringing the curtain down on the Wild West Outlaw era in proper Wild West Outlaw style.

The melting of the face might lead some to wonder if the body brought back was really that of Harry Tracy; after all, the reward on his head was huge. If we can believe then-inmate Joseph “Bunco” Kelley, though (not always a smart thing to do, although in this case it’s probably safe), the body that was brought back to the state penitentiary and displayed to all the inmates was definitely that of Tracy. (If you're unfamiliar with the story of Bunco Kelley, here's a link to the Offbeat Oregon column about him.) But Bunco did report something else that’s odd in this story: The body brought back to the pen that was identified as David Merrill’s, he says, was not David Merrill. It was someone else. In his 1907 book, Kelley writes that David Merrill’s ankle had a big, ugly scar from the many months he’d had to wear that “Oregon Boot” shackle. Kelley, who worked in the prison bathhouse as a trusty, had seen the scar many times. Merrill’s body had been found on July 14, after two weeks baking in the sun; and the face was unrecognizable. But the skin of the ankle was still intact … and unscarred. Of course, Bunco Kelley being Bunco Kelley, it’s probably not smart to take this as gospel. But it’s definitely not outside the realm of possibility that Tracy, knowing he was basically doomed, might have done his wife’s brother a final favor by letting him go home and framing up some poor bystander to stand in for his corpse.

|

Background image is a 2017 aerial view of Willamette Falls in Oregon City, by Mrgadget51. Source: Wikipedia Commons.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2021 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.