By Finn J.D. John

August 1, 2021

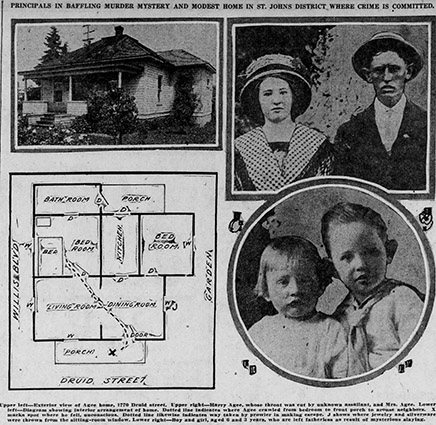

IT WAS A little after 10 p.m. on a Friday evening in the summer of 1921. In their little house on Druid Street in the St. Johns neighborhood of Portland, Robert Green and his family were getting ready for bed when they heard the screams.

Rushing to the front porch, they found their neighbor, Ann Louise Agee, in her nightclothes, wild-eyed and disheveled.

“Help! Come quick! They’re killing Harry!” she screamed.

Green looked across at the Agee home. From where he stood, by the light of streetlamps and the few lights inside the house, he could dimly see the front porch. The door was opening and a figure was staggering out of the front door, clutching at its throat. Then it collapsed on the porch.

Green sprinted across and leaped onto the porch. There he found his neighbor, carpenter Harry Agee, in a pool of blood, dying.

Looking up at him, Harry opened his mouth and tried to speak. Only a ghastly gurgling resulted from the effort.

Harry’s throat had been slashed open. Whoever had done it had missed the jugular vein, but had cut through his windpipe. Harry’s lips were moving as if he were speaking, but no words were coming out. It was as if he were trying to tell Green who had attacked him, but could not.

And before he could figure out a way, he lapsed into unconsciousness from the blood loss. He died a few minutes later, on the way to the hospital.

This was the opening act in a murder drama that would hold Portland spellbound throughout the summer of 1921 — and one that would convince thousands of Portlanders to lock their doors at night.

HARRY AND LOUISE Agee appeared to be a model couple. He was 29 years old, she 26. They had been married for nine years and had two lovely, well-behaved children, ages 2 and 6. They were relative newcomers to Oregon, having grown up on adjacent farms back east in the Ozark Mountains of Missouri, but had wasted no time getting socially plugged in in Portland. They attended church each Sunday, and were active in the Masons, Odd Fellows, and Woodmen of the World lodges. In fact, Louise was taking trombone lessons to play in the local Rebekah Lodge’s brass band.

Those trombone lessons were to play a somewhat sinister role in the events of that day.

Police were soon on the scene to investigate. What they found left them initially baffled. The house was disordered, as if a burglar had ransacked it, and some jewelry and other valuables had been collected and deposited under the dining-room window as if a thief had dropped them there. But the window was locked, and the things weren’t scattered as if thrown. Someone had either carried them around the house and placed them there, or locked the window after they’d been dropped.

A blood-spattered straight razor with a black handle was found in the middle of the street, 25 feet from the front door. Louise Agee told the police she didn’t recognize it, and added that Harry had only one razor, which was still in its box in the bathroom.

Looking at the bed, investigators could see that that was where Harry had been when attacked. Specifically, it looked to them like someone had stood directly behind the head of the bed and slashed with the razor, down and across.

Louise told them she’d been awakened by her husband yelling for help. Starting up, she first saw the blood, which frightened her; then she saw a man wearing a long overcoat and something white on his head, sprinting from the room and out the front door. She followed him, screaming for help. When she got to the porch, there was no sign of him; so she ran to the neighbors’ house for help.

It was hard to imagine a burglar slashing the homeowner’s throat on spec, as it were; and the valuables being placed on one side, with the murder weapon dropped on the other, made it seem unlikely this was a caught-in-the-act burglary. Suicide was briefly considered, but was ruled out based on how and where the cut was made.

That left the only other possibility: That it was an inside job — that is, that Louise Agee had slashed her husband’s throat as he slept peacefully in their bed.

By June 14, four days after the killing, the tone of the newspaper coverage was starting to harden against Louise Agee. That was the day the inquest was held, and Louise testified as a witness. She did not make a good impression.

“Mrs. Agee … said she and her husband retired Friday night at 10,” the reporter writes. “She went to sleep at once and was awakened by the screams of her husband, who cried ‘help.’ Dr. Frank Menne, coroner’s physician, who examined the body, had testified earlier that it would have been impossible, in his opinion, for a man having suffered such a wound to speak a word.”

No one reading the newspapers could possibly have been surprised when, the next day, Louise Agee was arrested. She and her trombone teacher, J.H. Klecker, both were lodged in the jail as “detained witnesses.”

It may not have been a surprise to newspaper readers, but it was clearly a nasty and unexpected shock to Louise.

“Placed in jail in the early afternoon, Mrs. Agee was as a caged tigress,” The Oregonian reported. “Asked by newspaper photographers to pose, she raged in fury when she thought her picture had been made and dared that it be run.”

“Tawny, reddish hair and her quick movements in the cell gave her a tigerish look,” the reporter continued. “She … was dressed in an attractive blouse of sheer silk and a checked sport skirt of modish cut, short, as the fashion is, with neat shoes and silk stockings.”

The reporter did not use the word “strumpet,” but one gets the distinct impression that he wanted to!

Louise Agee’s father, J.D. Swing, arrived later that same day, having traveled from his home in Missouri when he heard the news.

After her arrest, Louise Agee stopped talking to anyone but her attorney. Her stubborn silence seems to have annoyed the reporters, because shortly after this they started calling her “The Grim Widow” in the headlines, and missed few opportunities to mention her coldness of demeanor, sometimes even in the same sentence in which they describe her shedding tears.

Klecker, her trombone teacher, had no such reticence, and soon he had talked his way into becoming the state’s star witness against her. His testimony was that he and Louise had had a little affair going on in the months before the killing. He told the cops Louise had been wild for him, but he’d been uninterested, because he had a sweetheart in San Diego whom he had been urging to move to Portland and marry him. He had, however, succumbed to her seductive “Mrs. Robinson” moves once or twice in spite of himself.

“I’ll never give a woman trombone lessons again,” he said.

All of this, of course, was a classic boys’-locker-room story of the “panting vixen” type, and as such it’s pretty suspicious; but to the investigators it sounded legit. They theorized that maybe Louise, desperate to ensnare Klecker before his girlfriend came to town to claim him and finding that her marital status bothered him, thought she’d have better luck if her boring old husband were out of the way.

Through it all, Louise wore her stoicism like a mask, refusing to engage in any way.

“Mrs. Agee has already made a complete statement of all the facts so far as she knows them,” said John Collier, her attorney, in response to questions from the press. “Her statements have been distorted and garbled in building up a fabric of circumstances that can be used against her.” Therefore, he added, she had decided to say nothing at all.

She kept that silence up in the face of obviously severe temptations to break it. It probably helped her legal case, but it did her no favors in the “court of public opinion.” Even some of her neighbors and acquaintances started to turn against her, and to believe in her guilt.

AS PORTLAND DISTRICT Attorney Walter Evans and his team ramped up their case against Louise Agee, the tone of the newspaper coverage got darker and darker. At one point The Oregonian quotes prosecutors and investigators (anonymously, of course) as saying she was not acting like an innocent person, and even comparing her with Lady Macbeth — she of the Shakespeare play.

“She is regarded as a woman without imagination and to whom the finer feelings are undiscovered,” the Oregonian writes, describing the state’s position. “It is believed she could not know remorse. Bloody scenes could be endured, for they were details and a little blood could soon be washed away, and a state official connected with the prosecution quoted Lady Macbeth briefly yesterday, believing the words fitted into the character of Louise Agee: ‘The sleeping and the dead are but as pictures; ’tis the eye of childhood fears a painted devil.’”

This line, of course, was delivered in Act II of the play, just after the scene in which Lady Macbeth’s husband murders King Duncan in his sleep.

Meanwhile, members of Harry Agee’s family had started arriving from Missouri. The prosecutors likely expected to find in these in-laws allies who would help convict his wife of murdering him; but if so, they were surprised and disappointed. All of them were unwavering in their support of Louise and belief in her innocence.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: In "reader view" some phone browsers truncate the story here, algorithmically "assuming" that the second column is advertising. (Most browsers do not recognize this page as mobile-device-friendly; it is designed to be browsed on any device without reflowing, by taking advantage of the "double-tap-to-zoom" function.) If the story ends here on your device, you may have to exit "reader view" (sometimes labeled "Make This Page Mobile Friendly Mode") to continue reading. We apologize for the inconvenience.]

—(Jump to top of next column)—

|