TOLEDO, LINCOLN COUNTY; 1860s:

Col. Hogg’s war record: Marine highway robbery

By Finn J.D. John

|

The proposal went up the chain of command all the way to the Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen R. Mallory. Mallory responded by commissioning Hogg as an official Navy officer and instructing him to do exactly as he had suggested. Obtaining an official commission was probably a smart move on Hogg’s part. It would save him from being arrested and prosecuted as a pirate by the British, should he encounter them again. But it had the unanticipated effect of bringing the entire plot to the attention of a highly placed Yankee spy (whose identity remains unknown), somewhere in Richmond. As a result, when Hogg and six fellow Confederate Navy men booked their passage on the American steamer San Salvador in the territorial waters of neutral Colombia (f.k.a. New Grenada — the part we know today as Panama), the Yankees knew, in great detail, exactly who they were and what they were scheming to do. Of course, Colombia being Colombia, they couldn’t just haul off and arrest them on the spot. A ruse would be necessary to bait the rebels out into international waters, where arresting them wouldn’t create an international incident. No problem. The plans were in place well before the rebels arrived; when they did, the Yankees were waiting for them.

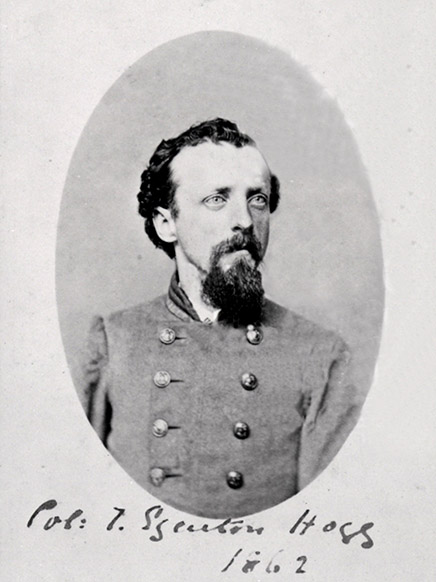

COMMANDER H.K. DAVENPORT, skipper of the USS Lancaster, was put in charge of laying the trap. Leaving his warship to steam on ahead into international waters, Davenport and a small contingent of officers and men stealthily boarded the San Salvador just a few minutes before the ship was to cast off. So that they could do this undetected, the captain of the San Salvador, who had also been put wise to the plot, summoned all the passengers to his cabin to examine their tickets and brief them on the voyage; while they were doing this, the troopers from the Lancaster were discreetly ransacking the entire ship, hoovering up every scrap of paper they could find. (One of the pieces of paper they found was the letter from Secretary Mallory commissioning Hogg to do the job.) Presumably then they retreated to the cargo hold or some similar place out of view of the piratical Southerners. Davenport then introduced himself to the pirates as an administrative officer from the ship’s owners, on board making sure everything was all right and that the captain and crew were doing their jobs properly; and as the San Salvador slipped away from the dock, he mingled freely with the passengers, chatting them up and putting them at their ease. All the while, the San Salvador was edging closer and closer to the boundary of Colombia’s territorial waters. Sometime that night, they caught up with the Lancaster, and all was in readiness for the springing of the trap. Davenport quietly gave the necessary orders and prepared to re-introduce himself to the San Salvador’s passengers … as the skipper of an American warship. “At daylight the next morning,” Davenport wrote, in his subsequent report on the operation, “being some 12 miles outside the territorial jurisdiction of New Granada, on the broad bosom of the Pacific Ocean, I ordered the ensign to be hoisted, assembled all the passengers, and then informed them that, in virtue of my commission, being now under the American flag, I desired the pleasure of the company of several of them on board my ship.” The would-be privateers were caught utterly flat-footed. They and their leader — T. Edgenton Hogg, Acting Master, Confederate States Navy — were out of action for the duration of the war.

HOGG AND HIS fellow privateers were brought to San Francisco for trial, where a military tribunal sentenced them to hang as irregular combatants in violation of the rules of war — that is, essentially, as spies. But even in the face of death the famous Hogg charm must have been broadcasting at full strength, because Union General Irwin McDowell decided to commute their sentences — Hogg’s to life on The Rock, and his accomplices to 10 years. All of them were out and free just a few years later, of course, when they received amnesty at the end of the war. And Hogg, finding himself at loose ends in the most dynamic part of the country and with the backing of a wealthy brother, must have marveled at the change in his circumstances a few short years had brought. The story of Hogg’s subsequent adventures as a railroad magnate in Oregon is almost as colorful, audacious, and just-plain-bonkers as his career as a pirate. But that’s a story for another time.

|

Background image is an aerial postcard view of Haystack Rock and Cannon Beach, from a postcard printed circa 1950.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2020 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.