COLUMBIA RIVER BAR, CLATSOP COUNTY; 1940s:

Ship’s sinking may have saved the lives of its crew

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

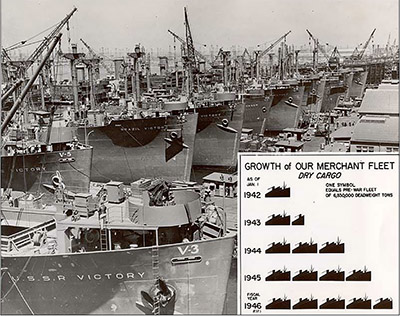

So it was with all these factors in mind that the U.S. War Shipping Administration commissioned a replacement for the Liberty, just a few months after Pearl Harbor. That replacement would become the Victory class. The Victory was an improvement in every possible way. Thanks to a massive power upgrade, it was over 50 percent faster — 17 knots, which is roughly the same speed as a surfaced German submarine — so it was far harder to put a torpedo into. It was bigger — 455 feet long and displacing 15,200 tons, versus 441 feet and 14,245, respectively. Then, too, it was far easier on the eyes than a Liberty ship, with a raked bow and an elegant cruiser stern. And to help address the cracking problem, the internal bracing was changed to make the hull less stiff. The very first Victory ship, the S.S. United Victory, slid into the water at Henry Kaiser’s Oregon Shipbuilding Company yard in Portland, in January 1944. From then until the end of the war, a total of 531 of them were launched from six shipyards — the largest number of them built in Portland — to join the 2,750 or so Liberty ships in Uncle Sam’s wartime production records.

THE DREXEL VICTORY was one of the last Victory ships built, in the waning months of the war. Now, two years later, she was making her way across the bar with a modest load of cargo bound for Yokohama, Japan, when suddenly something big and loud happened to the hull amidships — between holds 4 and 5. It was nothing as dramatic as what had happened to the doomed Liberty ships, but it was enough. Water poured into the ship; plates bulged under the sudden pressure. The crew got to the pumps and tried to keep up, but the ship was clearly sinking. By now the darkness was complete, but fortunately the weather wasn’t too heavy, so the Coast Guard motor lifeboat Triumph and cutter Onondonga managed to get the crew evacuated without any major trouble. Then the Onondonga tried to get a line on the drifting, unmanned freighter, hoping to beach her or at least make sure she didn’t sink in the middle of the channel. All efforts failed, though, and the sinking Drexel Victory drifted out to sea, wallowing lower and lower and finally sinking in deep water just offshore. So, what happened? No one really knows for sure. The captain was exonerated at the subsequent hearing; he’d had his ship in the channel, doing everything he was supposed to do, when it had happened. The Drexel Victory drew 30 feet of water fully loaded; the channel where she started taking on water was 60 feet deep. And the Army Corps of Engineers, surveying the channel after the sinking, found no obstructions there. So either the Drexel Victory rammed a derelict ship, or — as seemed far more likely — that pesky metal-fatigue problem that had plagued the older Liberty ships had not been completely licked. And if that was the case, the crew of the Drexel Victory had had a very narrow escape indeed. The bar that day had hit the ship with a few big swells, but nothing compared with what a good January storm can dish out on the north Pacific, between Portland and Yokohama. And if the hull had cracked as it did in the middle of one of those, there likely would have been no survivors.

|

Background photo is a hand-tinted image of Depoe Bay's famous Spouting Horn, published circa 1930 on a picture postcard.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2016 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.