LINN AND MALHEUR COUNTIES; 1900S:

Unwritten Law cases were not always moral failures

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

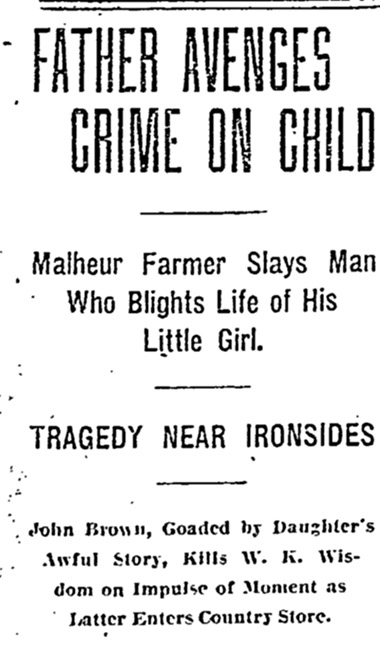

THE SAME WAS true, even more egregiously, in the 1908 case of a farmer from the Malheur County town of Ironsides named John Brown. Brown was having a rough year. His wife had left him five months before, leaving their five young daughters in his care; the oldest of these was Bessie, who was just 13 or 14 years old. About five months after Mrs. Brown left the family, Bessie came to see her father. She told him a family friend, Bill Wisdom, had been sexually molesting her since she was 11 years old. “At first, she did not know what it meant,” Brown told a newspaper reporter later. “When she got older, he made her do worse, and she began to realize more as she grew older what he was doing. Finally he got so brutal and unnatural that she made up her mind that she could not stand the life any longer, and she came and told me.” John Brown was momentarily at a loss. He came to town to talk to another friend, Ike Whitely. Whitely’s advice was very sensible: The damage was done, he pointed out, and any publicity would further traumatize the innocent girl. He urged Brown to leave the matter to him. He, Whitely, would confront Wisdom and tell him to leave the area and never return. Brown accepted this offer with thanks. The next day Brown was in town again, and saw that a flock of ducks had settled in a pond near town. Quickly he made his way to the general store and asked the owner, Ike Nichols, if he might borrow a shotgun. Nichols got one out, loaded it up and handed it over. Just then the door opened and Bill Wisdom walked into the store. Thus, John Brown suddenly found himself standing face to face with the man who, posing as a trusted family friend, had been secretly molesting his daughter for the previous two years ... and he was holding a loaded shotgun. The shotgun was, of course, loaded with bird shot. But from 10 feet away, it scarcely mattered. The news accounts don’t say if Brown stayed long enough to help clean up the mess he left on the floor and walls of Nichols’ store — just that he quietly went home to be with his daughters and to wait for the sheriff to come arrest him. Several weeks later, the grand jury met and — to the surprise of absolutely nobody — decided not to indict him. And afterward, not even the Portland Morning Oregonian — which by that time was on a virtual crusade against The Unwritten Law — vouchsafed a single word in disapproval. That wouldn’t be the case with another high-profile Unwritten Law case, though, which was coming a few months later in Portland. It would be another case of a jilted husband gunning for his rival, and it would fairly definitively put the would-be honor-killers of Oregon on notice that they could no longer expect The Unwritten Law to protect them. We’ll be finishing up this series of columns on the Unwritten Law with that story, next.

|

Background photo is a hand-tinted image of Tillamook Rock Light ("Terrible Tilly), published circa 1925 on a picture postcard.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2015 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.