PORTLAND, MULTNOMAH COUNTY; 1900s:

Cop-killer case helped

end Unwritten Law fad

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

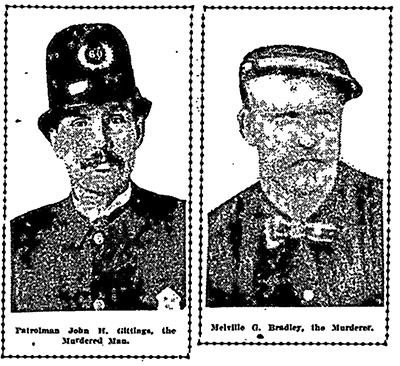

He then struggled to his feet, tottered a few steps, then collapsed into Sivener’s arms and died. Meanwhile, Bradley was running for home, where he got his hat and vanished. Authorities assumed he’d hopped a freight out of town. They angrily vowed to bend every possible effort to catching him.

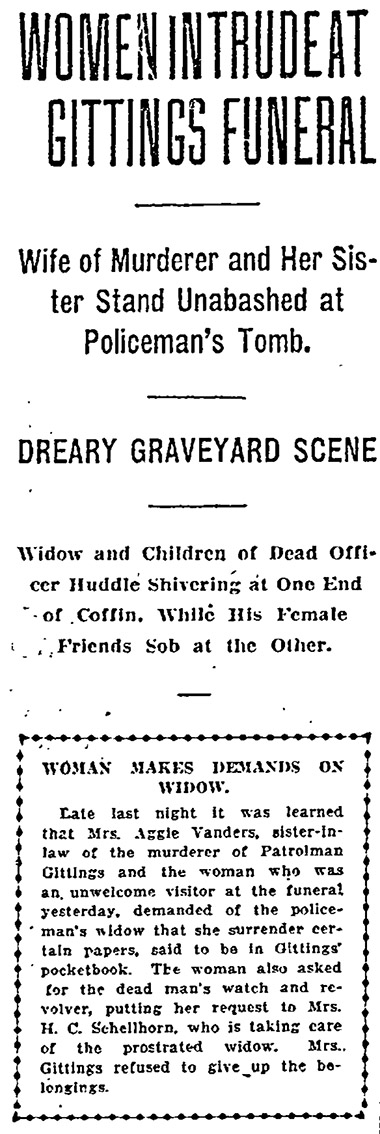

“There is plenty of evidence to show that there was very bad feeling existing between the two men,” the Oregonian reported; “that Gittings was friendly with Mrs. Bradley; that Gittings was friendly to and in sympathy with the members of Mrs. Bradley’s family, who were on bad terms with Bradley.” Just how friendly Gittings was with Bradley’s family — and with one member in particular — became obvious at the policeman’s funeral, held the following day. The funeral service was a fairly short one, and just as it was ending, a closed carriage raced up to the funeral home and three heavily-veiled women burst forth. It was Kate Bradley with her sister, Aggie Vanders, and one other woman whom the reporter didn’t identify. “My God, are we too late?” sobbed Vanders noisily. Upon being told that they were, Kate Bradley asked where the interment would be held. Upon being told, the three ladies bounded back into the carriage and raced away. The carriage caught up with the funeral procession, then passed it and raced on to the cemetery, where the three ladies installed themselves at the open grave to await the arrival of the casket. When it did come, they made a tremendous scene with noisy sobs and wails of anguish, as the dead policeman’s widow stood at the head of the grave, ashen-faced and trembling, quietly weeping and obviously trying to ignore them. Remember, these intruders were her husband’s murderer’s wife and sister-in-law. They were clearly the last people poor Mrs. Gittings wanted to see. But if their arrival was unexpected, it shouldn’t have been. The funeral director told the Oregonian’s reporter that Aggie Vanders, in particular, had visited the funeral parlor twice before to view the body — the first time on the day after the murder, a Thursday, on which occasion she “cried over the body until requested to leave.” “Friday she called again,” the article continues. “She threw herself across the casket, her sobs being audible throughout the building. After this scene she was not allowed to view the remains again.” The reporter then puts the pieces together — almost — with the next paragraph: “Mrs. Vanders has long borne the bitter hatred of Mrs. Gittings,” he wrote. “She lived next door to the Gittings shanty on Humboldt Street and Gittings spent much of his time in her company.” And if that weren’t enough to clue Portlanders in on what was really going on, there was this small item, run as a sidebar to the main story: “Last night it was learned that Mrs. Aggie Vanders … demanded of the policeman’s widow that she surrender certain papers, said to be in Gittings’ pocketbook. The woman also asked for the dead man’s watch and revolver. … Mrs. Gittings refused to give up the belongings.” The story was starting to smell more than a little bit sordid. But the real weirdness had only just begun. We’ll continue the tale in Part 2 of this story....

|

Background photo is a hand-tinted image of Tillamook Rock Light ("Terrible Tilly), published circa 1925 on a picture postcard.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2015 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.