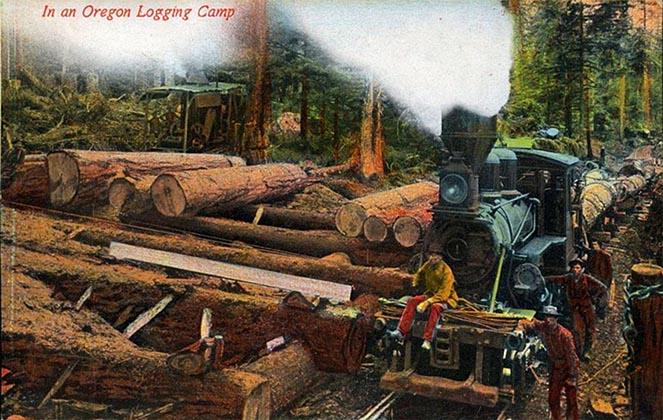

The life of a “Bull-Cook”:

A day in a 1920s logging camp

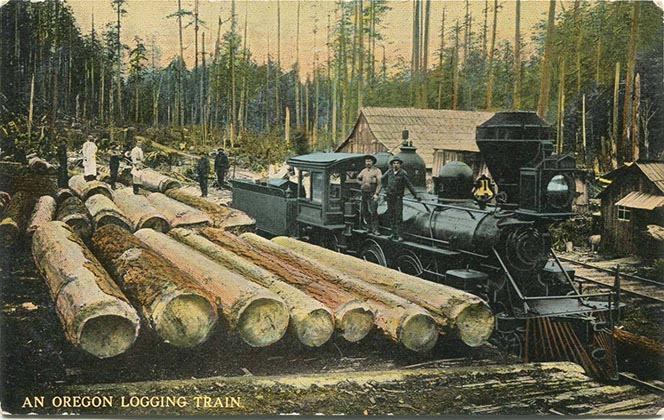

Legendary Oregon writer Stewart Holbrook worked in — and wrote about — the rough-hewn logging camps that peppered the Oregon woods from the late 1800s through the 1930s. This is one of those stories.

By Stewart Holbrook — July 1926

Editor's Note: This article first appeared in The Century Magazine in its July 1926 issue, on pages 289-294.

When a writer on the World’s Greatest Newspaper in the Literary Capital of America does an extremely red-blooded poem about a bull-cook who not only serves puddings and swell pies to his jolly companions, those rough, big-hearted, snuff-chewing men of the logging-camps, but who is so important in his occupation of bull-cook that he may with impunity tell the camp foreman where to head in, why, it is time some one of the lumber-jack cognoscenti got busy and did something about it. This business of urban pressmen attempting to wear red mackinaws has gone far enough. At least two novelists and three poets have gone astray in the simple matter of bull-cooks; all of them guessed wrong.

A bull-cook, despite the “Chicago Tribune,” does not cook. He never did cook. And as for riding roughshod over that martinet of the woods, the camp foreman, it simply isn’t done. He got his alluring name many years ago when he was the fellow who, among many other duties, shook out the baled hay, mixed the bran and corn meal, and fed the oxen, or bulls, as they were then termed. He also had charge of policing the bunk-house, if the company he was working for pretended to any sort of official scavenging. To-day there are no oxen in camp, and the bull-cook is merely the man of all work, the chore-boy around the bunk-houses. His name has prevailed, however, despite abortive attempts of uplifters to rechristen him with what they said was “the more self-respecting title of camp helper.” Camp helper! Shades of Paul Bunyan! Thanks to the loggers’ sense of the utterly ridiculous, this truly awful baptism never graced even camp pay-rolls, much less been accepted as a part of speech among the boys.

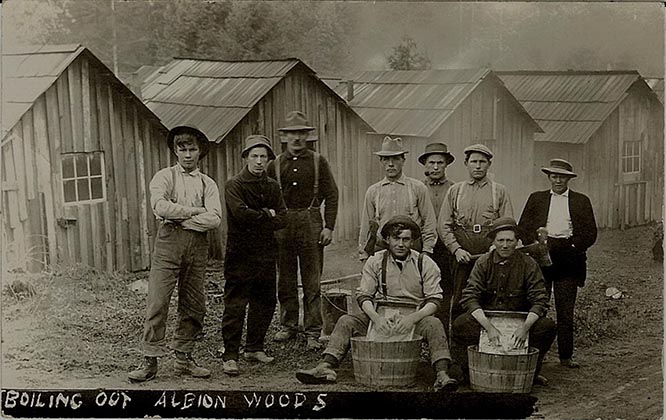

They already had a second-string name of their own for the bull-cook, anyway, crum-boss being the title, the crum part of the neologism having reference to the Pediculus vestimenti (lice) with which so many camps were, and still are, infested. In northern Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and Quebec the bull-cook is often known as the bar-room man, this because he cleans and fills the lamps, sweeps the floor, and otherwise has charge of the bar-room, the part of camp where the men sleep.

But these are provincial slang. Bull-cook is national in its scope. In every logging-camp, from the old Bangor Tiger district of Maine to the wild, Douglas fir country along the Washington coast, you will find a quite generally forlorn character with watery eye and huge walrus mustache. This is the bull-cook. He is hardly the eminent person you would expect to meet, if your conceptions had been formed by the reading of Chicago poetry and New York prose.

Many of the bull-cooks are broken-down old alcoholics, hopeless mentally and physically. Others are simple-minded hired men, removed from their original environment of back-country farms and placed in the big timber. Not a few of them are mild cranks. Whether the occupation of bull-cook is attractive to queer working-stiffs, or whether the job itself possesses pathogenetic properties, I do not know, but it is a fact that the great fraternity of crum-bosses and bar-room men harbors within its ranks more strange characters than do certain state legislatures.

Most bull-cooks take themselves seriously. Few are given to I.W.W.-ism or have any sort of “radical tendencies,” although they are often gifted debaters on such subjects as religion, prohibition, and the open shop. I knew one bull-cook who was enmeshed in the mystic waves of color therapy, as emanated from the prophet’s headquarters in a small New Jersey town, and another who was a fully ordained saint in the small yet ebullient Church of the Voice of Elijah. Others, more worldly fellows, chew snuff or plug tobacco, and will readily peruse odd copies of the “Police Gazette” which stray into camp. Virtually all of them are devotees of an eminent savant of the old school whose austere features grace the label of every bottle of a certain “pain-killer,” an ancient camp remedy of great power, the thaumaturgic properties of which, I am told, have not been impaired by the Volstead Act.

It is five o’clock in the morning when the bull-cook begins his day. After he shakes himself free from under the heavy sugans on his bunk, he first takes a rare, or pinch, of snuff, if he is that kind of a bull-cook, and then pulls a pair of baggy trousers over a suit of vermilion underwear, used also in lieu of pajamas. I have known but one bull-cook who was not partial to cheery red underclothes; he wore none whatever.

With his trousers hung well up under his arms, a pair of old rubbers on his feet, the bull-cook is ready. He snaps his Police, Firemen’s, and Postmen’s galluses twice. Bring on the day!

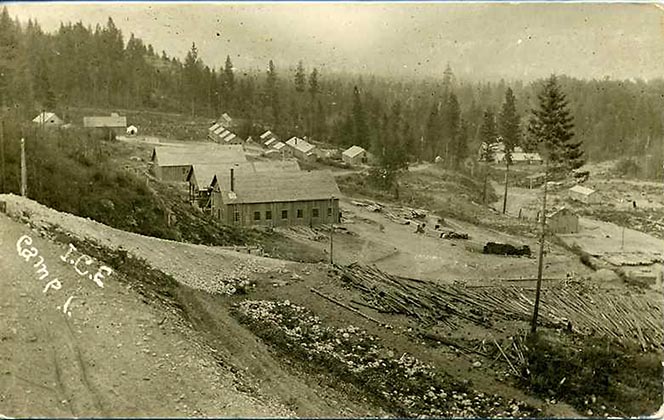

The fog is low and the air chilly as he comes out into the deserted camp street. The silence in the bunkhouses is broken only by the breathing of hard-sleeping loggers. Far off on the mountain a fox barks. Crows can be heard faintly from somewhere beyond the low-hanging mist. Dawn is breaking in the timber.

Contrary to company rules but in keeping with best traditional practice, the bull-cook takes, from where he has cached it the night before, a can of kerosene, and proceeds from shack to shack, lighting fires in the bunk-house stoves. Here is where the bull-cook shines. He is the greatest fire-maker of all time. Indians, Boy Scouts, and directors of Woodcraft, all of whom lay great stress on their ability to kindle fires, are as tenderfeet when placed alongside a good bull-cook. His fuel is often green and full of sap or rotten as punk, but his fires never fail. In twenty minutes he has a well regulated blaze in each of the twenty stoves.

With the snap and crackle of a score of fires on the early air, the bull-cook, if he happens to be on good terms with the cook, goes to the kitchen for a cup of coffee. The hot brew makes a new man of him, and he comes out to greet Aurora with a feeling of importance. For isn’t he the man who starts the wheels turning in the morning? He sniffs the air a moment and looks up the mountain, where the sun has broken through the mist. He observes that the wind is in the north and is steady.

He considers the antics of two or three crows humped up on an old snag near the pig-pen. All bull-cooks are weather-prophets. He tells the cook that the day will be fair and warm…. It is half-past six; time to wake the boys.

Sounding reveille in camp is as much a ceremony to the bull-cook as the military reveille is to the sergeant bugler. Most bull-cooks privately pride themselves on the tune they play on the iron gong for first call, and they are forever experimenting with new beats and flourishes. Sleepy but interested, I have often sat up in my bunk to compare the matins of Elizar Therrien with those of Charley Olafson, both able men with the gong. Elizar had the dash of a Sousa, while Charley’s motif was more on the order of “The Blue Danube.” But the art of gong-pounding, I believe, undoubtedly reached its height under the inspired hand of one English John Thomas, a short-stake (yery migratory) but remarkable bull-cook who was equally at home on Puget Sound, in northern Minnesota, or along the swift water of the upper Kennebec. John was reliable only for the first thirty days in camp. He could control his thirst for but approximately that period, and then he would have a session with “pain-killer,” or would draw his pay and drag her for town. But how he could play that gong! His was sheer artistry. I have known foremen who in spite of John’s widely known failing would hire and rehire him. They liked his tunes.

This musical gong is a triangular piece of steel, hanging just outside the dining-room door. At about six or six-thirty in the morning—this depending on whose camp it is—the bull-cook approaches it, a short bit of iron in his hand. He looks at his watch, and when the second-hand has made its last revolution within the half-hour, he smites the home-made gong a single lusty blow. The echo reverberates through the silent forest, strikes fair against the mountain, and is thrown back to camp. It is a wonderful noise! The bull-cook’s eyes gleam; here is the big moment of the day.

Now he begins his tune. He starts with a leisurely movement, three sustained bell-like notes, pealing like the crack of doom into the ears of sleepy loggers. When the last note is just dying he starts his roulade. Faster and faster he beats the vibrating triangle. The very hills seem to tremble. This is Big Medicine! Before his morning overture has reached the quick notes of its final measures the camp is astir. Stray practice curses roll out of bunk-house doors. The tramp of steel-calked boots. A voice raised in ribald song. Wash-basins clatter. The bull-cook’s chest swells. When he rings the gong the boys have to get up!

Immediately after breakfast, for which a cookee beats the call, the bull-cook takes his sap-yoke and freights swill to the pigs. All bull-cooks enjoy the porkers. They have names for their favorites, and they talk to them, jolly them, chide them.

I knew a Canayen bull-cook who used to sing his pigs a song that began:

“Cochons, cochons,

Mojee, batan!

Vous etes les memes

Comme allemands.”

It was his contribution to the great war against the Hun. Scandinavian bull-cooks enjoy giving a pinch of snuff to the pigs, just to see them sneeze. This seems to tickle the Norsemen.

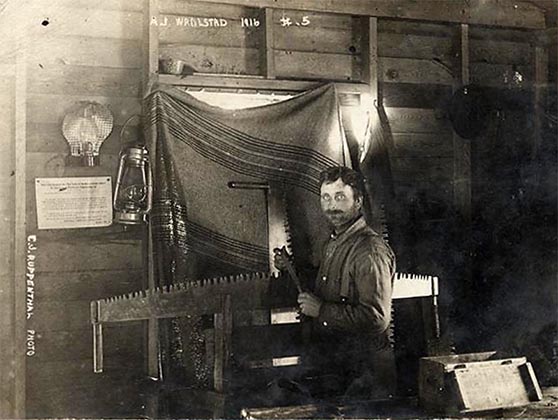

When the crew has gone to the woods the bull-cook starts his morning tour, filling and cleaning the lamps and sweeping the shacks. His method of lamp-cleaning is one of the finest things of its kind I have ever seen, and I wonder that farmers’ wives have not adopted it. He first places all the lamps in a row on the floor. He grabs a chimney, shoves it once into a pail of hot water, and sets it upright on the still warm stove. He repeats this with each globe.

The result is astounding. Steam from water clinging to the inside of the chimney cleans the glass and leaves it with a polish that would shame crystal. A squirt of kerosene in the lamps, and the job is done. The bull-cook wastes no motion.

Sweeping the bull-pen, or whatever shack is used for Saturday-night and Sunday poker parties, is the only particular sweeping the bull-cook does. Here the work is done carefully. Nickels, dimes, even quarters, are to be found. I knew one bull-cook whose subsequent life was made unduly expectant by his finding a twenty-dollar gold piece in a crack of a bunk-house floor. He never repeated.

Sawing and splitting wood for the cook-house come next, and this feat often involves arguments with the cook as to what is nice dry wood and what is not nice dry wood. If he constantly supplies the chef with a good quality of fuel the bull-cook can generally become a stockholder in the cook-house supply of prune-juice whisky and elderberry wine. But even with these inducements for mutual respect, feuds between cooks and bull-cooks are very common.

At some vague hour in the afternoon—just when I have never been able to ascertain, although I have often attempted to stalk him—the bull-cook slinks away to his lair in his little shack and there takes a snooze. What romance comes into his life also appears during the afternoon rest period. Somewhere within the bowels of his bunk he has secreted a journal, the masthead of which proclaims it to be “Wedding Bells: The Matrimonial Journal That Gets Results.” This is the consequence of sending a two-cent stamp to an idealistic concern which permanently advertises for lonely men. I have never known or heard of a bull-cook who was immune to an ably edited paper devoted to the hornswoggling of senile bachelors and paretic widowers. Once exposed to a page covered with atrocious half-tones of mate-seeking females, and he is lost. The great indoor sport of logging-camps, matrimonial correspondence, is the bull-cook’s form of golf.

I once acted as scrivener to a bull-cook in his affair with one Mrs. Violet Grace — a buxom widow of somewhere in Ontario, who, according to her own admission in the columns of “Wedding Bells,” was “attractive, aged 39, dark hair, blue eyes, worth $2,000, with prospects of $1,200 more.” After a lengthy correspondence, my bull-cook Romeo sent her a money-order for $125, as proof that he would like to have her meet him in Seattle “for purposes of getting a preacher, any kind will do, and getting married.” But she never put in an appearance, although the money-order was duly cashed.

The last time I saw this bull-cook he told me he had located another Violet in Colorado. You simply can’t kill a bull-cook’s faith in matrimonial publications.

It is four o’clock. The bull-cook yawns. He gets up, snaps his suspenders, and emerges from his den. The sun is making long shadows, and the air has taken on the chill of the evening. The pigs are grunting, clamoring for him. From afar off in the woods he can hear the faller’s warning cry of “Tim-ber!” as a big fir crashes to the ground. Pans clatter in the cook-house. An aroma of baking beans is wafted through camp.

Business of lighting fires is repeated. At the last bunk-house in the street he turns and with a vague sense of Service proudly surveys the little curls of smoke, each identical with the others, so even are his fires, winding straight upward from the stovepipes. He goes to the washhouse, where he stirs the never-dying fire in the big barrel-stove. A mild yet scornful curse escapes him when he notices a suit of B.V.D.’s hanging from a drying-line.

Swill comes next. The pigs riot when they hear him coming down the trail to the pen. They always know him, he thinks; a sort of paternal feeling. He knows they never make such a noise for anyone else.

Why, all those hogs are dependent on him! He dumps the garbage into the trough and watches them fight for places.

Shouts and joyful cries from the bunk-houses tell him that the loggers are home from the woods. Supper-time nears. In front of the dining-room a crowd of lumber-jacks is waiting for the cookee’s signal for mulligan. Camp etiquette keeps them outside the door until the gong rings. But the bull-cook, thanks to an ancient tradition, never waits in this queue. He is allowed to enter the sacred precinct through the stage-door of the kitchen. This, so far as I know, is the sole courtesy allowed the bull-cook; he is already seated when the crew rushes in, a favor of no mean value, as any logger knows.

The bull-cook’s after-supper duties are few. He makes sure that the chef has plenty of kindling for morning, and he sees to it that the fire in the foreman’s shack is burning brightly. He always makes a call or two at some of the bunk-houses to hear what the boys are talking about. The subject is generally the same: “When are you goin’ down?” This old topic is ever fresh and alluring. To men exiled in camp there seems little else worth talking about. “Goin’ down,” to the logger, means going to the city — any city. He’s going to drag her. He’s going to tell the timekeeper to make her out. He’s got her made. He’s staky. In other words, he has withstood the abnormal life of a logging-camp as long as he feels he is able, although he does not think of it that way. The various expressions are as well understood in Maine as they are in Oregon.

Somewhere around nine o’clock the bull-cook retires to his little shack where the pretty movie queens of magazine covers look down at him from the four walls. Paradise! After spelling out a few pages of “Harry Tracy, the Lone Bandit,” he prepares for bed. He takes from his trousers pocket a great silver watch which he will tell you has a genuine P. S. Bartlett movement. None better than a Bartlett, he says. He winds it and hangs it on a nail near his bunk. He cracks his galluses twice and disrobes into the glory of his brilliant underwear.

“Ninety-three days more,” he reminds himself, as he looks at the saw company’s calendar on the wall. He has in mind the number of days’ work necessary before he will have enough money to go to town.

Low mutterings and the riff of pasteboards float on the night air … the plaintive notes of an accordion are faintly heard, coming from the shack where the Finn buckers live … a coyote barks on the mountain … the drip, drip, drip, of water in the wash-house … the weird call of a hoot-owl … wind sighs down the stovepipe of the shack … ninety-three days more … sleep … The bull-cook’s day is done.

Editor's Note: This magazine article is in the public domain due to non-renewal of its 1926 copyright. It is therefore not subject to Offbeat Oregon History's usual Creative Commons license, or to any other copyright restrictions of any kind.