A legendary 1800s circus man talks about Big Top life

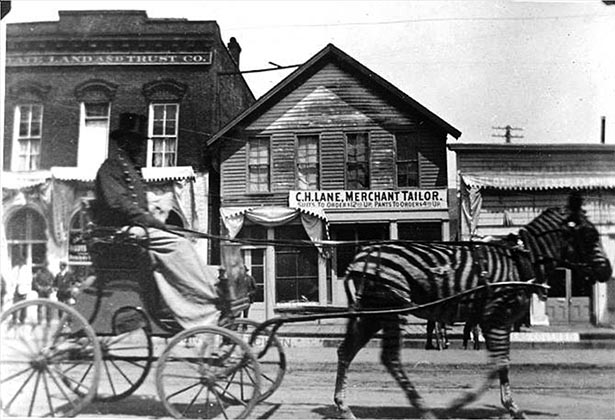

At the age of 91, "Doc" Van Alstine was a living legend among circus people when he gave this interview. He recalls a lifetime of traveling and performing — with train wrecks, dangerous animals and the occasional tornado.

By A.C. Sherbert — January 13, 1939

Editor's Note: Over four afternoons in July of 1938, Works Progress Administration writer A.C. Sherbert interviewed a 91-year-old circus legend: W.E. “Doc” Van Alstine. The interviews took place in Doc’s room at the Jefferson Hotel, situated at the corner of First and Jefferson in downtown Portland; Sherbert described this as a “typical third-rate hotel, room small, meagerly furnished; iron bed, small dresser.”

According to Sherbert’s notes, Doc retired from active circus life in 1917, and since that time made his home in Portland.

“Circus day in Portland is a red-letter day in old Doc's calendar of events,” Sherbert continued. “The big shows never forget him, and when they arrive in Portland, Doc is always presented with a generous supply of ‘Annie Oakleys’ (passes). Surrounding himself with a bunch of his cronies from the Plaza Blocks, Doc and his party are the first ones on the lot, and though a nonagenarian, Doc misses nothing that happens during the progress of the performance, and is alert to even the slightest deviation from conventional circus routine.”

Doc worked as a house painter when he came to Portland, but hard times came with the onset of the Depression, and at one point he found it necessary to live at the Multnomah County Poor Farm. With the passing of the Social Security Act, however, Doc was able to leave the County Farm and move into the city.

Sherbert described him as looking “younger than age claimed,” with iron-gray hair, oval face, dark complexion. Arthritis made it hard for the old gentleman to walk, but when he stepped out he always wore his “old-fashioned black derby hat, with wide rolled brim.”

An interview with a big-top legend:

I was born in the little town of Kinderhook, New York, in 1847. My father was Dr. Thomas Van Alstine, who later served as a surgeon in the Union Army during the Civil War.

At an early age I had a yearning for the show business. School didn't interest me a bit. I hated books. I wasn't a danged bit interested in reading about what somebody else did, or where they went, or what they saw. I wanted to go, do, and see things for myself, and I couldn't think of any better way to satisfy my ambition than to join up with a circus.

School, in my day, wasn't much like it is now. Boy, oh boy, in them days if you didn't toe the line you got what was comin' to you. Teachers and parents both, in them days, had spare-the-rod-spoil-the-child ideas, and if a youngster didn't do exactly what he was told, they used to lay it on plenty with a hickory switch, or somethin' just as good.

Come a day, once, when I was a young gaffer in my early teens, I had a chance to run away with the Mighty Yankee Robinson Circus. The lure of sawdust and spangles was much stronger than family ties or the red schoolhouse, so off I goes. I was only with the circus four days when I was dragged home to the family fireside and my place at the table, but not without a trip to the barn first, where my father strapped me around the legs and across the back with a tie-strap until I wasn't hardly able to navigate. As tough a lickin' as the old man gave me, I soon forgot it — but I didn't ever forget my first four days with the circus.

Doc's first days in the circus

The thrill of them few days with Robinson's circus stuck with me through more than a half century of circus troupin'. I was hired as a "block" boy. The block boy had to help set up and "strike" (tear down) the "blues" (cheap-seat bleachers). Incidentally, general admission circus seats has been blue as far back as I can remember. There wasn't no commoner job on the circus, but I remember how proud and thrilled I was merely to touch a piece of circus equipment: the blocks, the angle pieces, the seat boards — anything that was a part of "the circus.”

And I remember how I gazed in awe at the performers, and to think I was so close to them. I seen a lot of beautiful women in my day, but I don't believe I ever seen a woman in my later life that looked so beautiful to me as them circus women did. I had the feelin' that they was queens, or goddesses, or somethin' too beautiful to belong to this world. And I recall the thrill of thrills when a clown — circus folks call the funny men "Joeys" — said, "Hey, lad, run out to a butcher shop and get me a pound of lard." The Joeys used lard for taking off their "clown white", or make-up. I was so excited at havin' a performer actually speak to me that I couldn't say yes or no. But with the ten cent piece he give me clutched tight in my fist, I run like lightnin' to the nearest butcher shop. Boy, oh boy, was I happy!

Back to school, and boring life

I well remember when I goes back to school after my four days with the circus. I cut quite a figger among the handful of bumpkins that was my schoolmates. Bein' with a circus made me a hero among them youngsters, and did I glory in it. I knew I'd have to stay in school awhile longer — I couldn't help myself, but in the back of my head I know that when I got a little bit older I was goin' to join up with a circus and be a showman for always, and always.

My family was determined that I was goin' to be a doctor, like my old man was. They insisted that I take up the study of medicine and follow in my father's footsteps. In them days, anybody that thought they was cut out for it, could be a doctor if they wanted to. All you needed was a little schoolin' and be handy around sick folks and not be afraid of the sight of blood. All medicine was bitter, if it was any good, and if they didn't know what ailed a person they 'cupped' him and drew some blood. Then he either got better or worse, as God willed. I might of made a good doctor, at that, if I only could of got show business off my mind.

When I got a few years older, I was able to out-talk the old folks and get my own way. I give up all thought of pill-rollin' and left home to join a circus, and I stuck with circuses for nearly sixty years of my life. Studyin' for a doctor, though, give me the nickname, "Doc", and wherever on this globe the gray dawn sees a "big top" bein' raised, that's the name I'm knowed by.

Comparing new and old circuses

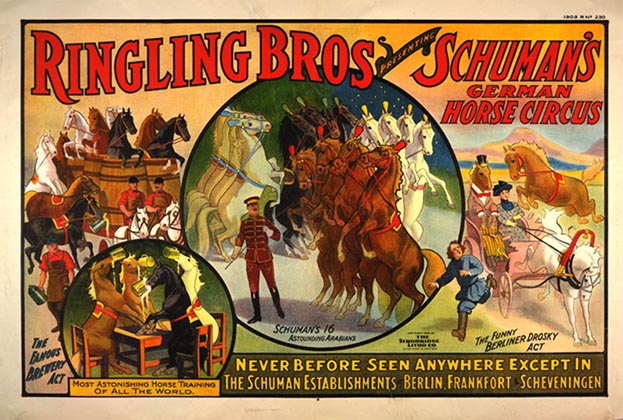

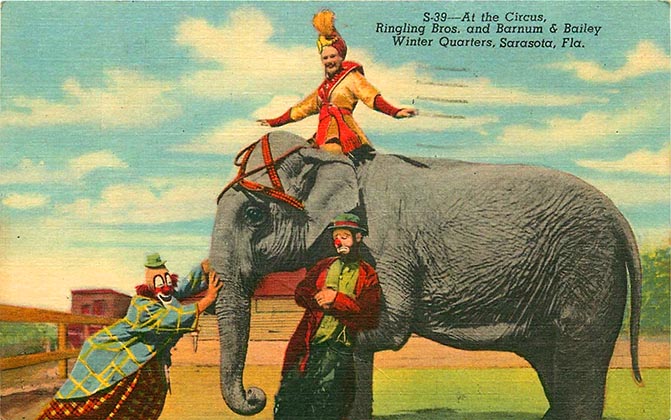

I been asked to draw a comparison between the circus of today and the circus of the past. Well, they just ain't no comparison. The circus in this day and age seems really to be the stupendous, gigantic, colossal exhibition the advance billing and the "barkers," "spielers," and "grinders" claim for it. The oldtime circus was a puny forerunner of the mammoth aggregations now on the road. The circus your grandfather went to see as a boy, was nothin' more than a variety, or vaudeville, show under canvas. Pretty near all the acts they done in the circus could of been put on in even the ordinary theaters of that time. Could you imagine the Ringling Brothers' B & B show of today tryin' to squeeze itself into any theater, auditorium, or indoor arena in any town, say, like Portland?

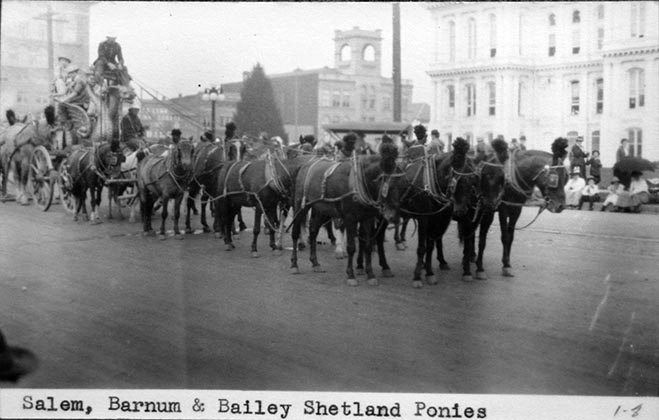

The people who works for circuses today is all trained specialists. Everybody has only one job, and he's supposed to do that one thing well. The oldtime trouper was a Jack-of-all-trades. He could shoe a horse, if he had to, he could clown, drive a ten-horse team, lay out canvas, and fill in at anything around the lot except perhaps aerial acrobatics, and believe it or not, many of the old-timers could even "double" in acrobatics.

The circus has always been one of the world's most progressive enterprises. New inventions, if they was something the circus could use, was grabbed up by the circus as soon as they come out. The circus was always away ahead of anybody else in lighting equipment. When stores and business places throughout the country was still using tallow dips for light, the circus was using calcium flares bright enough to almost blind you. The pressure gaslights used by circuses in the early part of this century was intensely brilliant by contrast with the dim, dinky lights of the average town the circus visited. Many small-town oldtimers will tell you they first saw Edison's marvelous incandescent lamps when some circus came to town.

Yes, the circus of today is bigger and better in every way than circuses was, even twenty-five years ago. But the kids of today ain't so wide-eyed and amazed at what they see at a circus as they was a quarter of a century ago. So many marvelous things goes on all the time in this day and age that kids probably expect more from a circus now than it's humanly possible to give.

Tornadoes and train wrecks

In my more than a half century with circuses I worked on all the big shows one time or another. The circus has took me to the far corners of both hemispheres, and has give me many exciting experiences. I seen circuses miraculously missed by cyclones in the prairie states. When you're standin' in the middle of a couple million dollars' worth of circus equipment, it's always a thrill to see a blackish, greenish cloud with its trailing, death-dealing funnel, bearing down on your show. The 'stock' in the 'animal top' (menagerie tent) knows a storm is comin' same as you do. Makes you feel kind of funny in the pit of the stomach, to hear them snarl, howl, whine, bellow and roar as the storm gets nearer. They get nervous, testy, mean, and it all adds to the confusion on the lot.

I was with a show in Hutchinson, Kansas, once when a twister didn't miss. As the twister's whirling funnel came towards us, all hands got busy and begun grouping all loose and movable equipment and gear and lashing everything together with tie ropes and tie chains. The animal wagons was hastily covered. We drops all canvas flat to the ground and strikes all poles. We didn't have much warning. A few seconds later the twister was upon us and cuttin' a swath right through the center of the lot. We was what you could call lucky, though, because nobody got seriously hurt and we didn't lose no stock (animals). But the big top was picked up and torn to shreds, and small parts of it scattered all over the surrounding country.

Train wrecks is another thing. I been through many small wrecks in the course of years of troupin', and was also in one disastrous crackup. The railroads in the old days didn't have no block signal systems like they got now, and as circus trains was always extras and not regularly scheduled trains, wrecks was frequent. At Gary, Indiana, I was with Sells-Floto circus, when we had a wreck where over a hundred persons was killed, and a lot of valuable stock was lost.

Fistfights with the town yokels

A "Hey Rube" is practically unknown today. A “Hey Rube” was a fight between the circus folks and the town yokels. These ruckuses used to came regularly every so often in the old days. Many of the “Hey Rubes” was started by folks figgerin' they wasn't gettin' all the circus advertised; if the stupendous wasn't stupendous enough, the gigantic wasn't gigantic enough, the colossal wasn't colossal enough, or the "largest in captivity" wasn't large enough, the town folks felt like they had grounds for a fight. Another common cause of “Hey Rubes” was because petty thieves, purse-snatchers and pickpockets, followed circuses from town to town. The circus got blamed for what them slickers did, but they was nothing they could do about it. When the crooks hit a crowd too hard, and too many people got plucked, the town folk got together and tried to take it out on the circus people. Pretty near every “Hey Rube” I ever seen ended with the town folks comin' out second best physically, although the circus usually lost out financially. Lawsuits always followed a “Hey Rube,” and circus people had no chance for a square deal in a prejudiced small-town court.

I was in a “Hey Rube” in Lincoln, Illinois, once. It was one of the toughest battles I ever seen. The town boys was coalminers and same of the toughest customers I ever seen. We strung out in a circle around our stuff and stood 'em off with "laying out pins" and whacked 'em with "side-poles", finally giving 'em the run, but they sure could take it. Another “Hey Rube” in Ann Arbor, Michigan, was started by a gang of students from the University of Michigan, for no good reason at all except perhaps they thought it was funny. It cost the circus I was with more than $35,000 in lawsuits and damage to equipment. In a “Hey Rube,” most of the lawsuits that follow is usually by some innocent bystander who gets hurt in the scramble.

Circus people: Once social outcasts

The circus owners — you name 'em, I worked for 'em — were all big men of fine character. Everyone of the big circus owners was a square-shootin', two-fisted boss, and not a sissy among 'em. I knowed the Ringling family well — the seven boys and their father, Gus Ringling. Gus Ringling was a harness-maker, and teamster, before he went into the circus business. Gus wasn't ever able to hire a better teamster on his show than he was himself. Old Gus could handle a twelve horse team so slick that the string of horses would form a perfect circle, and the lead team could eat oats from the back of the wagon Gus was sittin' in.

Circus people in the old days was considered social outcasts. "Decent" people wouldn't have nothin' to do with troupers. This attitude on the part of "outsiders" towards show-folks, brought the show-folks closer together — made 'em clannish. Circus people was just like one big family, and was always a good lot, and always willing to help each other over the bumps. People don't look at it the way they used to, any more, but circus people is still clannish just the same.

Modern methods and high specialization has made it a lot easier for the circus man. Transportation is improved, and accommodations is a lot better than they was. You don't have to be tough inside and out, to troupe with a circus nowadays. In the old days any handler of circus stock knowed how to mix up a batch of kerosene or paregoric liniment to dope an ailing animal. Nowadays the big show troupes [have] a staff of veterinarians, and each valuable animal is watched as close and its diet figgered out as carefully as for the Dionne quints [the first quintuplets to survive infancy, five girls born to the Dionne family of Ontario in 1934].

In the ring with a jungle-born cat

I got a lot of respect for Clyde Beattie and other of today's animal trainers, but I don't think there is any comparison between the temper and ferocity of jungle-born cats that the old-time trainer faced twice a day, and the animals born in captivity that the present-day trainers work with. You don't hardly ever hear of a trainer gettin' killed in an exhibition cage today; but in the old days I have seen trainers torn to ribbons in the twinkling of an eye.

The circus reached its greatest size in 1908. After that year they never got any bigger. In 1908 Ringling Brothers introduced the first "spec," or "spectacle." Since that year the "spec" was a feature with all circuses. The first spec was called "King Solomon" — later specs were the "Durbar at Delhi," "Arabian Nights," and others. I was boss canvasman for many years with a number of different circuses. Boss canvasman is a good job on a big show and pays from $75.00 to $100.00 a week. I made quite a lot of money in my day, but I haven't got anything to show for it now. As boss canvasman, I seen the sun rise in every town of importance in the United States. Most of my real old time friends of the circus have passed through the "connection" to the "other side." (The “connection” is the opening and runway through which the performers and animals enter the “big top” during a performance; by this, Doc meant his friends were mostly dead).

Doc comes to Portland

Portland, Oregon, has always had the name of being a good show town. I visited Portland with big shows many times before I quit the show business. I quit the show business twenty years ago, and came to Portland to live. I figgered I was gettin' too old to be galavantin' all over the country. Since then I have made a living as a house painter, and am now the oldest active painter in the Painters' Union at Portland. Yes, I learned to paint while in the show business. Many a piece of show equipment, wagons, platforms, etc., I painted for the circus.

The show business may be a hard life, but if I had it all to do over again I would still want you to give me the same route. It's been a "long haul." I've passed the ninetieth "flare," and feel like I'm standing outside the "connection" waitin' for the whistle.

(A "long haul," or a "long haul town," is a town in which the railroad loading spur is situated a long distance from the circus lot. "Flares" are kerosene torches set out along the way from the loading spur to the lot to guide the teamsters. As flares are usually placed two to a block, ninety flares would indicate a long haul. In other words, old Doc has passed the ninetieth milestone, and feels that he hasn't much farther to go. "Standing outside the connection waitin' for the whistle"... Performers, acts, animals, etc., stand outside the connecting entrance to the arena for a short time before they are summoned to enter by the shrill note of the "routine director's" whistle).

(Source: Library of Congress American Life Histories, https://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/wpaintro/wpahome.html -- edited by Finn J.D. John, March 21, 2013)