Old Hankins' Round-Up

Just one thing was precious to the bitter, coldhearted old cattle king: his three-year-old grandson. But when a hated neighbor rescued the little tyke, at great risk to her own life, it changed his attitude forever.

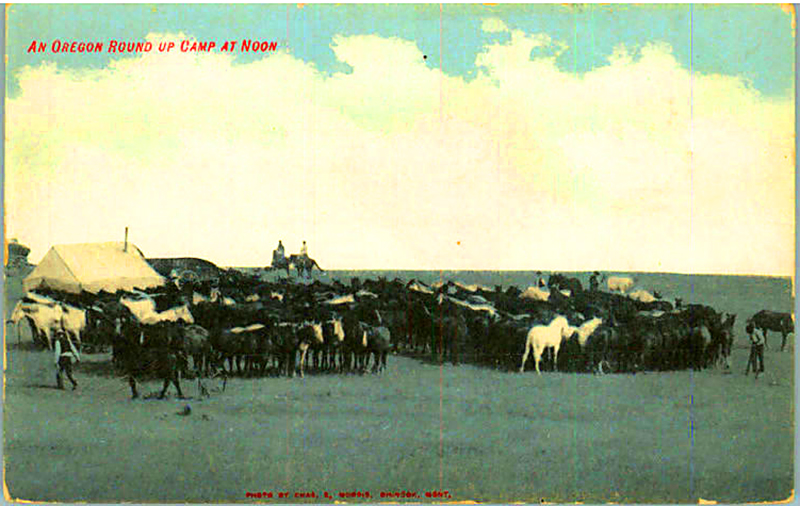

A herd of cattle on the high country of north central Oregon, near the

scene of this apparently fictional story.

By Adonen — May 1899

Editor's note: This brief short story remindsy me a great deal of "How the Grinch Stole Christmas." No information is given as to whether it has any basis in reality, so it must be assumed to be purely fictional. From geographical references it appears to take place somewhere east of The Dalles, on the Oregon side of the Columbia River. Enjoy! — fjdj

He heard his wife calling excitedly to him as he rode by, but would not turn his grim old face that way; though he did give one swift glance to see if Wedgie, his dead daughter's little son, were there. That three-year-old tyrant was the one person before whom old Hankins became humble. His wife and college-bred son must do as the Washington cattle-men had done: keep out of the way.

Little by little Hankins’ ever-increasing herds had swallowed up those of the smaller stock-raisers. Whole bunches of their cattle disappeared in a night: and one brave fellow who resisted the raiders went down with a bullet through his head. But Old Hankins grew rich, built a modern house, and if there was little love for him in the embryo city, why, he was a good hater himself.

The one man whom he hated most cordially was his near neighbor, MacLomond. The hardy Scotchman had made the most effectual fight against the diminishing of his stock. By his shrewdness and native perseverance he had more than once made the old cattle king hand over. And on one occasion, when a bunch of steers were being driven toward the boundary regardless of their various brands, MacLomond's daughter, Leava, had been in the saddle sixteen hours in order to meet the cattle thieves with the sheriff and posse. She saved the cattle, but the herders escaped, and every one knew it was Old Hankins’ money that helped them across the Columbia.

Well, the old cattle king hated Mac as the best of us hate what we fear: and next to her father, he favored Leava with his sincerest curses. At first he was disposed to look with contempt at the slight figure and fair, freckled face, with its frame of heavy red braids; but after the episode of the sheriff and posse, and one other, he changed his mind.

The other [episode] took place when Leava began teaching the district school. Hankins slyly hinted to three of the roughest boys who attended the school that there was a pony apiece for them if they would run the teacher out. Of the three, one had become her brightest pupil, the other her stoutest champion, and the two had given the third boy a whipping he would not forget that term.

And the only time the old man had been angry at Baby Wedgie was when, acting as usual upon his own advice, this independent infant had visited the school. The indignant grandsire towered over the small autocrat and thundered, “How dared you visit that that hussy?”

When young Al Hankins came home that night, his father ordered him to go over and forbid Miss MacLomond to allow Wedgie to enter the school-room.

Al returned from his errand two hours later, and said of course he did not insult the young lady by mentioning it. Indeed, he thought it would be a good plan to take Wedgie over to school for an hour every day. At the dinner table he absently asked his father to pass the dimples, and the next day walked over to MacLomond's with a book Leava had expressed a wish to read. The heavens did not fall on him, but Old Hankins did, and in the domestic earthquake that followed his mother quietly sided with Al.

So today the old cattle king was rounding up his steers with a savage look in his black eyes, and an ominous squaring of his iron jaws. He was hot and dusty and furious.

A dozen fat steers had broken away, and for once he had failed to cut them off. He was angry at himself for refusing to hear what his wife had called to him as he passed the house. And now, right in the face of his ill-temper, Leava MacLomond came dashing up the lane on her little black horse, directly toward the tramping herd of excited cattle.

Her horse must be running away with her or she would never ride to almost certain death like this. But the drove was going slowly, and she might have time to turn her pony and escape yet. Then a worse devil than he had ever before harbored took possession of Old Hankins' heart.

The girl had halted just in front of the oncoming mass. She must have lost her presence of mind, for she dismounted. As the old man saw her bright braids and jockey cap on a level with the tossing herd, he broke into a fierce yell, spurred his horse and cracked his long stock whip, startling the frightened cattle into a wild stampede.

Through the dust he could see her trying to regain the saddle, as the frightened herd charged down upon her. Her horse was true and steady, but she was unusually clumsy about mounting; for twice she was almost in the saddle, only to stagger back among the sharp horns and bloodshot eyes. The old man could not turn his murderous eyes away, and an oath bolted through his clenched teeth, as with torn jacket and bloodstained face she mounted and dashed down the lane.

But the oath changed to a prayer, the first he had uttered in forty years, a wild prayer for God’s mercy and help. For the wounded girl, swaying dizzily in the saddle, the reins swinging loose on the horse's neck, her right arm hanging helplessly by her side, clasped with her left a little figure whose dirty pink dress and brown curls belonged only to Wedgie.

They tell yet of the leap Old Hankins made over the board fence. They say no racehorse ever covered the distance in the time he got to Leava's side, and caught her and the boy from the horse.

“He’s all right,” she said, wiping the blood from her cheek and smiling in the old man's ashen face.

“Me wunned away to help gwandpa herd,” Wedgie explained.

No one ever knew of that awful deed in the hard old heart. For in the days that Leava was imprisoned with a broken arm, he so haunted the MacLomond ranch, begged so hard to be of service and seemed so happy to give her any pleasure, that the family quite took to him. And in the delight of being “took to,” Old Hankins blossomed into a really neighborly old rascal.

Wedgie and Al are both frequent visitors at the school; and when his son looks over to the light in the MacLomond window of an evening, Old Hankins says sweetly, “Go on, Al, I'll do the chores.”

— Reprinted from The Pacific Monthly magazine, Portland, Ore., May 1899