The Hermit of the Siskiyous

The citizens of Betsyville proved less than hospitable to a mysterious stranger, and after he left they never did find the source of all the gold he found. (A short story reprinted from The West Shore magazine.)

By Henry Laurenz — January 1887

Here stood, a quarter of a century ago, in the heart of the Siskiyou mountains, a rude cabin of poles and brush, thatched with closely packed branches of young firs. The exact location matters little, for the iron finger of Time has effaced all traces of its existence, and demonstrated the mutability of all things terrestrial, even in those mountain solitudes. Many years ago the poles and brush were swept by a landslide into the noisy, dashing stream flowing through the gulch at the base of the hill, far up on whose side stood the cabin, while a giant fir, whose grasp upon the earth was thus loosened till it succumbed to the power of the west wind and toppled to the earth, now lies prostrate and broken across the site of this once-humble habitation. Even the rude trail that wound tortuously through the dense forest and along the bank of the rapid stream, is now so completely obliterated by the rains and snows, so blocked by fallen trees and masses of earth and rock, brought down the mountains’ steep sides by the melting snows and copious rains of each vernal season, that he would indeed be well-skilled in woodcraft who could successfully trace it from the old mining camp whence it started, some four miles down-stream, to the site of the vanished hut. Time was when this desolate spot was the center of an absorbing interest for scores of human beings; but now few know that it ever existed, and fewer its exact location, while the incident I am about to relate has already been relegated to the domain of fiction or legendary romance, save by the few survivors of those whom the shifting kaleidoscope of life brought for a brief period in contact with the peculiar and mysterious being who built and occupied this rude habitation.

The Siskiyou mountains lie on the border line of California and Oregon, stretching westward from the Cascades to the Coast range. They form the dividing ridge between two great rivers, both of which have cleft deep passages through the obstructing Coast range, and pour their annual floods in deep, rapid and turgid streams between the lofty walls of rugged rock which confine them to their narrow channels. The Klamath, in California, and the Rogue, in Oregon, are alike in all their essential features, turbulent, impetuous and unnavigable. From the dividing ridge of the Siskiyous, each receives a multitude of effluents, both small and great, which pour down, in noisy haste from their birthplace amid the springs and melting snows of the mountain summits.

On many of these streams gold was discovered early in the “fifties,” and for a number of years every bend and flat was the scene of mining operations of the primitive rocker or long-sluice character.

In some of these localities, where the extent of mining ground was comparatively large, or which were so located as to be a convenient central point for several outlying districts, quite extensive “camps” sprang up and flourished for several years. Some of these have still a sort of post mortem existence, though the great majority of them have lost all material being, and are rapidly falling into the obscurity of things forgotten.

During the mining period referred to, such a camp as I have described stood upon one of the larger tributaries of the Klamath, flowing down the southern slope of the mountains. It occupied an abbreviated flat at a bend in the stream, first known as “Sailor's bend,” because “color” was originally found there by two adventurous seamen, who had deserted their vessel to experience the hazards, privations, excitements and golden possibilities that made up the sum of the pioneer miner's existence. Later, when half a dozen brush and shake shanties centered about a larger and more pretentious structure of logs, shakes and canvas, which did duty as a store, saloon, post office, gambling hall and general social rendezvous for the miners along the stream for several miles above and below, it was christened “Betsyville” by some facetious miner, in a moment of witty inspiration, and wore the title proudly until its last occupant deserted it, and left its dilapidated structures a prey to the elements.

Although a night never passed without the exhibition of considerable animation at Betsyville, Saturday night was the “one bright particular star” of its septuary round. It was then the whole population of the neighborhood gathered at the rendezvous, and partook of such good cheer as “Big Johnson” was accustomed to dispense. It was an occasion of much good natured hilarity, merging, upon occasion, into boisterousness, on the part of some of the convivials whose supply of brains was not sufficiently weighty to keep down the Cain-raising tendency of Big Johnson's liquor. All such were endured as long as there remained a shred of virtue upon which to hang endurance, and were then summarily quieted by Johnson, to the thankful relief of his less noisy patrons.

Cards, jokes, stories, yarns, cigars, pipes, together with frequent indulgences in whisky straight, supplemented, at times, by the rasping tones of a tortured fiddle, squeaking out its enlivening accompaniment to a reel, hornpipe or a genuine “stag dance,” made up the sum of the night's entertainment, which very seldom ended before the brightening of the eastern sky heralded the approach of the Sabbath sun. Sunday was a day of rest, if not devotion. Avaricious indeed was the man who worked in his claim on the Sabbath. This much of the influence of the habits of other days still clung to them. They observed the fourth commandment, so far as to “remember the Sabbath day,” but almost to a man they neglected the injunction “to keep it holy.” Sunday was a day for doing all sorts of odd jobs — for washing clothes, splitting wood, buying provisions at the store, mending tools and clothing and, in the afternoon and evening, resuming at Johnson's the thread of enjoyment where it was broken off the night before. Sunday night was very similar to its predecessor, though the zest and freshness that had marked the revelries terminating the week's labor had passed away.

It was in the midst of such a scene as this, late one Saturday night, that a stranger entered the door, which stood hospitably open, though, if the truth be told, Johnson, in opening it, did so less from the promptings of a spirit of hospitality than with a desire to exchange some of the foul, whisky-laden atmosphere of the interior for the clear and uncontaminated air of the mountains.

The newcomer stood for some minutes quietly watching the hilarious company, attracting but a casual glance from the revelers, for strangers were too common in Betsyville to be objects of curiosity.

The mines, at that season, were thronged with men, constantly coming and going, and scarcely a night passed that half a dozen of them did not sample Johnson's fire-water before seeking a couch beneath the spreading branches of some not-distant fir or, in rainy weather, rolling up in their blanket to “court the balmy” upon the floor of the saloon, despite the hilarity of the more wakeful guests. No attention was, therefore, paid to the newcomer, until he stepped up to the rude bar, made of a slab sawed from the side of a log and turned with the bark side downward, and offered Johnson a dollar for the loan of a blanket until morning.

A man without a blanket in the mountains was as rare a sight as one without a horse on the plains, and in a short time every pair of eyes in the room was carefully scrutinizing the stranger. He was a tall man, of refined features and expression, polite in his manner and dignified in his bearing, and yet the fact that he was traveling without a regular outfit created such a suspicion in the minds of the proprietor and his patrons, that the object of it could not but see it reflected in their countenances.

Johnson gruffly said he had no blankets to lend, but would sell him one for ten dollars. The stranger at once turned on his heel and passed out the open door as silently and unexpectedly as he had entered.

A few days after this incident at Betsyville, a miner whose claim was located farther up the stream noticed, while following down its banks on his way to the camp, smoke rising through the tree tops on the side of a little gulch leading upward from a flat along the stream.

Curiosity led him to follow up the bank of the little brook, which poured in alternate foam and crystals down its steep and rocky bed, and see who was camped in that beautiful, but lonely, spot. Ascending a few hundred yards, he observed a rude cabin of brush and poles, standing a little back from the brook.

From a clay chimney, protruding from one comer of the structure, issued the column of smoke which had first attracted his attention. He climbed the bank and entered the cabin, expecting to find the owner within, as he had observed no signs of his presence on the outside.

The hut was empty, not only of the owner, but of everything which could be classified as furniture or domestic equipments, save only a few freshly cut fir boughs in one end, which were evidently used as a bed, and a clay fireplace at the other end, in which was blazing a fire of dried branches, whose ragged ends gave evidence of having been broken by hand. There was neither axe, spade, pick, nor, in fact, any article whatever usually seen about the cabin of a miner, and no camping utensils of any kind. The hut was, evidently, but two or three days old, and was just such a structure as a man of intelligence and ordinary ingenuity could erect with the aid only of a large pocket knife.

The thick branches which formed the corner posts and cross pieces, among which the lighter ones were entwined to make the sides and top, had been sharpened with a knife and driven into the ground with a large stone, as the whittlings, discarded branches and discolored stones scattered about on the outside plainly witnessed.

There were signs of a meal having been cooked, but no preparations for another were visible, save only the blazing fire and a few sharpened sticks with charred ends, which had evidently been used for broiling spits. The intruder waited some time for the return of the unknown occupant, and then, his desire to reach camp conquering his curiosity, be left the place and resumed his journey down the stream to Betsyville.

In the course of his stay in camp he made inquiries about the owner of the hut, only to learn that its existence was unknown to the frequenters of Johnson's. Only he and the mysterious builder had, probably, ever set eyes on that rude brush habitation.

His curiosity was now doubled, and on his return the next day he again paid the hut a visit, accompanied by one of the regular residents of Betsyville, who was also desirous of learning the identity of the new settler. He was again disappointed, for the cabin was still deserted, although there were a few observable traces of the presence of some person in the hut since the day before, not the least of which was the fact that a fire was still burning so freely as to indicate that it had been replenished within the past half hour.

When this intelligence was carried back to camp, it created considerable discussion among the frequenters of Johnson's establishment. There was nothing remarkable in the fact of some stranger having built a hut, for prospectors were continually locating and housing themselves in temporary shanties of brush. What made this case the subject of curiosity, and even suspicion, were the two facts that the hut had evidently not been constructed by a person possessing a miner's, or camper's outfit, and that the owner had apparently gone into hiding to avoid meeting his visitors.

When Saturday night came, and with it the usual influx of miners from the more distant claims, the subject of the mysterious person who had built a brush hut with his jack-knife received more serious attention and a free discussion.

Sluices had been robbed in times past, and it was the general sense of the crowd that a man who would build a hut must be either a genuine miner or a man who expected to gain a living in some illegitimate way. The result of it all was that the following day, Sunday, an informal committee of half a dozen miners paid the new comer a visit.

As before, the occupant of the strange cabin was not at home, and the unbidden guests were compelled to act as their own entertainers. They could find nothing but the bare walls of the hut, the remains of a fire, evidently several hours extinct, and a few crude utensils, such as could be fashioned with a pocket knife, from the branches of neighboring trees. Nothing whatever could be found to indicate the method by which the mysterious builder of the shanty gained a livelihood, except that the slender skeletons of a few mountain trout, and the cleanly-picked bones of birds, bore evidence to the fact that game constituted a portion, at least, of his daily food. There was but meager satisfaction to be gained from a contemplation of these remains, and a general feeling of irritation at having their curiosity baffled deepened their already unfavorable opinion of the stranger.

“This here is onreasonable,” said Bud Jackson, a tall Missourian, who had preferred rabbit hunting to grammar, in his youthful days. “No man hain't got no right to live this a'way. I'm the last man in the world to interfere with a man's nateral rights, but this here is a'goin too fur, an' I move we make him stop it.”

“What ye goin' to do 'bout it?” queried Joe Coombs, a delegate from Indiana, whose incessant praises of the muddy Wabash had won for him the title of “Wabash Joe,” which name was the only one known to belong to him by anyone in the camp, except himself and Johnson, in his official capacity as postmaster.

“What 'ud I do? I'd pull his dem'd shanty down and stick up a notice to clar outen these here diggins.”

“Don't you think that would be a rather summary proceeding?” quietly asked a young doctor from New York, who had spent two years in the mines in an unsuccessful effort to acquire riches from the ground, in doing which he continually spent the various sums paid him upon the rather infrequent occasions when his professional services were required.

“A which?”

“I mean that it is my opinion we had better find out a little more about this matter before we take such decided action as you propose,” said the doctor, who had come with the volunteer committee rather for the purpose of exerting a restraining influence than with any motives of curiosity.

“That's all right, Doc, but how are ye goin' to find out. This makes three times now, an' he ain't never to home.”

“Oh, yes he is, this fire shows that.”

“Well, he hain't here when nobody else is.”

“That is because we do not come at the right time.”

“Well, what 'ud you do?”

“Why, I move that we pin a notice on the side of the cabin, telling him to come down to Johnson's and see us.”

“Keerect!” exclaimed Wabash Joe. “That's the ticket. You write 'er, Doc.”

Taking a letter from his pocket and taking it from the envelope, he turned the latter over and wrote on the back, as follows:

You are respectfully requested to come down to Johnson's, immediately, and make a few explanations to the citizens of Betsyville. This invitation is very urgent, and a compliance with it is recommend by the —COMMITTEE.

“That's the cheese! Stick 'er up an' lets git!” exclaimed Bud, with enthusiasm.

The notice was accordingly affixed to a twig, and then fastened at the cabin entrance, where it could not fail to be seen, and the committee departed in far better spirits than they had felt a short time before. The informal report they made to the citizens of Betsyville and vicinity was satisfactory, inasmuch as it seemed to assure them that the mystery would soon be cleared up, and the miners turned their thoughts ·from the brush hut and its builder to a fuller consideration of the customary convivialities.

Time passed, but the invited guest did not visit Johnson's. Thus for two weeks the matter stood, and then, after a somewhat heated discussion, another Sunday visit was paid to the brush hut, this time by a regularly appointed committee, who were expected by their indignant constituents to “do something.” As on former occasions, the shanty was found without an occupant. The notice had been removed, and there were other evidences of the recent presence of somebody, chief of which was a freshly kindled fire, burning in the rude fireplace.

“I reckon he saw us a oomin', and cleared out,” said one of the committee.

“That's it,” said another. “And I move we give him just ten minutes to come back again, or down comes his shebang.”

This proposition received varied and characteristic expressions of approval, and, during the period of suspension of execution, the more curious of the visitors critically examined the surroundings of the cabin. A trail, not yet made very distinct by use, was found leading up the gulch, and this was followed with considerable eagerness, until, about three hundred yards from the hut, it became too indistinct to be easily traced. Careful inspection showed that the reason of this was, that the person who used the trail branched off in a score of directions, evidently with the purpose of preventing the making of a beaten track, by which he might be followed to his destination — at least, that was the conclusion at which the investigating committee arrived, and it served to fix them in their previous conviction, that the cabin was a nuisance which ought to be abated.

More than three times the stated ten minutes having now elapsed, and the mysterious stranger not having put in an appearance, the sentence was quickly executed. It took but a few minutes to demolish the hut and pile its constituent parts in a heap, with half a dozen large boulders placed on the top; but the work of writing a second notice to quit was one requiring more time and effort, since the doctor was not present to take charge of that Herculean task.

Wabash Joe, having seen the doctor write the other one, was looked upon as the most competent to undertake this literary effort, and to him the task was unanimously delegated. This question having been settled, the more practical one of what to write with and what to write upon, claimed attention, and here was a difficulty which nearly relieved Joe of his onerous duty, since neither pen, pencil nor paper had been brought from Johnson's. After much deliberation, and while various suggestions of a highly impracticable nature were being showered upon him, Joe suddenly sprang from his recumbent position beneath a large fir, and exclaimed: “You fellers just hold your clack a minute, and I'll fix this thing in no time,” and he began hastily to descend the side of the hill to the stream below.

“Go it, while you're young,” shouted one of them, while the others laughed, as the momentum which Joe acquired in his descent began to render his movements far more rapid than graceful.

The laugh deepened into a roar, interspersed with cat-calls and shrill whistles, as Joe lost his footing entirely and rolled like a log to the bottom, only saving himself from plunging into the creek by securing a firm grasp upon a bunch of willows growing on the bank.

Spending but a moment to take an inventory of his scratches and bruises, Joe began walkiug along the bank, peering intently into the water, his movements closely watched by his companions above, who were full of curiosity as to the meaning of his actions. He soon stepped down to the margin of the water, and was for two minutes lost to sight. Then he reappeared, bearing in his arms a large flat stone, worn smooth by the action of the water. After considerable puffing and blowing, he climbed the hill, and, throwing the stone upon the ground, sat down to rest.

“What you goin' to do with that 'ar?” asked Bud Jackson, while one of the others took occasion to remark that a man was “a dinged fool what 'ud roll down hill arter a stone, when the mountain was full of 'em.”

“Never you mind,” said Joe, with a look of wisdom and confidence in his countenance. “You fallers just hold your wind, and I'll show you a little Injin business I learned when I was a kid, on the Wabash.”

Joe quickly gathered an armful of sticks and kindled a fire. He then stood the stone up on its edge, the smooth side turned toward the blaze, and propped it up with a few stones and a short stick.

He then sat down again, filled his pipe, lighted it, and, reclining on his elbow, began to smoke in the most unconcerned and contented manner.

“What's all this funny business?” asked one, whose curiosity and impatience began to get the better of him.

“That's all right. Just you wait a few minutes, and you'll know all about it.”

Thus admonished, the remainder of the committee followed their scribe's example, and soon each several individual was industriously engaged in sending upwards frequent puffs of smoke to mingle with the darker variety from the fire in contaminating the pure atmosphere of the mountains.

In about ten minutes, the stone became sufficiently dry to suit the scribe, and he arose from the ground, put his pipe in his pocket, drew out his knife, and sharpened the end of a stick he had previously selected. This he thrust into the fire, and left it there until it had become charred.

“I hain’t as much of an artist as I uster was,” said he, as he took the stone and propped it up against a log, at a convenient angle for writing. “And I never was quite equal to them old master fellers; but I reckon I can sorter put somethin' on this 'ere stone as that 'ar feller will understand the meanin' of.”

With this remark, and with the committee standing at his back and on either side, Joe, after much effort, and several recharrings of his stick, succeeded in producing the following brief, but intelligible, illustrated inscription upon the stone:

This met with strong expressions of approbation from the entire committee, and, fastening the inscribed stone securely between two of the boulders which crowned the heap of brush once constituting the hut, they departed, in high spirits, for Johnson's, where they related the details of their expedition to a large and interested gathering, the narrative being frequently interspersed with libations.

Thus, for several weeks, the matter rested. No more was smoke seen to rise from the site of the demolished hut, by travelers along the trail at the base of the hill, and that the mysterious sbanger had heeded the warning of the committee, and taken his departure, no one doubted.

* * *

One day, there came down the trail from that direction, a man leading a pack mule, upon which was loaded the usual miner's outfit. He stopped at Johnson's and purchased a number of articles, offering, in payment, a small lump of gold, such as was common in the diggings. Johnson recognized him instantly as the man who had, about two months before, interrupted the Saturday night convivialities to request the loan of a blanket. It was not infrequent for a miner to be broke one month and have plenty of “dust” another, and so Johnson's suspicions were not aroused; but he had a curiosity to know where the man had struck it so rich, and remarked: “You seem to have hit it about right, stranger.”

“Yes, I have had very good success,” replied the man in a dignified and refined tone.

“Where a bouts, may I ask?”

“Oh, up the creek a short distance,” said the man, as he nodded to the proprietor of Betsyville, and resumed his journey down the trail.

A few days after this, Wabash Joe felt a prompting to visit the site of the demolished hut. It must be confessed that this impulse was not a supernatural one, but the extremely natural desire possessed by every new candidate for literary honors. He was anxious to learn what effect his literary effort had produced, and with what kind of treatment it had met at the hands of the stranger to whom it was addressed. Accordingly, he took no companion with him on his visit.

Upon arriving at the scene of his artistic labors, he went, at once, to the pile of brush upon which his tablet had been deposited. There it was; but it had been laid down flat upon the brush between two boulders. Lying thereon was a piece of paper, held down by a weight, and when his eyes rested upon this they swelled to wonderful proportions. He seized it and eagerly turned it over and over in his hand. It was a piece of rotten quartz, as large as a walnut, and threads of free gold were protruding from it on every side. He estimated its value at fully one hundred dollars.

He opened the paper, and read, with deepened interest and astonishment, the following letter:

To the extremely curious and gentlemanly Citizens of Betsyville, at Johnson’s assembled, GREETING:

Not in compliance with your extremely kind and urgent invitation, but because I have made enough in the past few weeks to last me the balance of my days, do I take my departure and leave you this farewell message. To you, jointly and severally, I present my ledge of decomposed quartz, which has made me rich, and which will make you all equally rich, if you find it. In witness thereof, I have hereunto affixed this specimen of its contents, and my name, on this, the third day of September, in the year of grace, 1854.

JAMES WATSON.

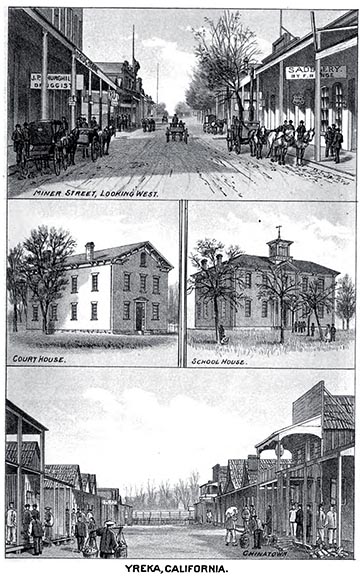

As soon as he fairly comprehended the import of the letter, Joe hastened, with all speed, to Johnson's, where he duly exhibited it and the specimen to the eager Betsyites. The excitement created was the greatest known in camp, and this was intensified when Johnson related his interview with the stranger, and it was discovered that the date of his appearance and departure toward Yreka corresponded with the date of the letter, or deed of gift. For the next two weeks, the mountain in the vicinity of the demolished hut echoed to the tread and shouts of the eager Betsyites; but their most diligent search met with no reward. No trace of the ledge of decomposed quartz could be found, and not the least sign of mining operations, other than those well known before, were to be seen within a radius of several miles.

Inquiry at Yreka, by one of the agents of Johnson, who visited that great mining center, developed the fact that about a week after the date of the stranger's departure, a man entered that city with a pack mule, which he sold at auction in the street. He then purchased a Wells, Fargo & Co. draft, on San Francisco, for $70,000.00, and took his departure in the stage. The gold paid for the draft was coarse, and a portion of it was mixed with quartz, showing conclusively the character of the diggings from which it came. This, combined with the fact that no robbery was reported, and that no claim in the vicinity of Betsyville produced any such specimens as that the stranger had left as a witness to his deed of gift, was conclusive evidence, to the minds of many, that the ledge of decomposed quartz had an existence in reality, and that patient search would surely reveal its locality.

The most enthusiastic and persistent prospector was Wabash Joe, who retained possession of the specimen nugget as the perquisite of his literary genius, and who devoted his entire time to the work of discovery, until, at last, having exhausted all his means, lost his claim, and even been compelled to sell his talismanic specimen to procure the necessary “grub” upon which to live while prosecuting his search, he abandoned the camp in disgust, and was seen among the convivial crowd at Johnson's no more. From that day to this, not a year has passed that someone has not made an effort to discover the “hermit ledge,” as it is known by old-timers.

Yet, under the new order of affairs, and under the excitements of more recent events, the story of the Hermit of the Siskiyous and his ledge of gold finds but few to relate it, and fewer still to give it credence.