Oregon’s Liberty Ship factory: Building ’em faster than Hitler could sink ’em

At Henry Kaiser's Portland shipyard, a champagne bottle was getting cracked over a brand-new bow every three days throughout the war

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2017 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

One of the last two surviving Liberty ships, the S.S. Jeremiah O’Brien, sails

along the Northern California coast. Built in the “other Portland” – in Maine --

the ship is a popular tourist attraction in San Francisco. (Photo from S.S.

Jeremiah

O’Brien)

By Finn J.D. John — May 2, 2009

Most Oregonians have some idea what Liberty ships are: Simple steam-powered freighters built with frantic speed and in staggering numbers by American shipyards during World War II – with the stated goal of building ‘em faster than Hitler’s boys could sink ‘em.

In this, they were wildly successful. American shipyards cranked out roughly 2,750 of these ships during the first five years of the 1940s – during which time the minions of Messrs. Hitler and Tojo only managed to sink about 200. One was actually built in just four and a half days. And these weren’t small ships. Each one was 441 feet long and 56 feet wide, and could lug 18 million pounds of Jeeps, airplanes, soldiers or anything else without being overloaded – which they frequently were. A 2,500-horsepower steam engine pushed them to a pathetic, but adequate, 11 knots.

This cell-phone video shows the engine room of the Jeremiah O'Brien during

one of the days when its boilers are fired up and its 2,500-horsepower triple-

expansion engine is run. This particular engine was used in the James

Cameron movie Titanic, by the way. (Video: F.J.D. John)

Liberty ships were not exactly objects of beauty. President Franklin Roosevelt at the time referred to them as “a dreadful-looking object,” and most people thought he was right. They were considered expendable and not expected to last more than five years. But they were more than just cannon fodder. One of them drew first blood on the water during World War II when it sank a German raider in an old-fashioned gun battle in 1942; there was a war on, so many of the ships went to sea bristling with cannon barrels, some as big as five inches.

There would have been a lot fewer of these ships, though, had it not been for the man who owned the Oregon Shipbuilding Corp. in Portland: Henry Kaiser.

The Jeremiah O'Brien at the dock, ready to receive visitors, in San

Francisco. That's Alcatraz in the background behind it.

(Photo: F.J.D. John)

Kaiser owned seven shipyards around the country, including the Oregon one. What made the local yard special, though, was that it was specifically set up to produce Liberty ships, and it was set up in the most efficient way possible – like an assembly line.

In just under four years, Portland cranked out 455 of them. In other words, a brand-new freighter was getting a champagne bottle broken against its bow roughly every three days. It all ended, of course, with the war; the shipyards were shut down. The ships they produced soldiered on for years, but just two survive today – both museum ships: The John W. Brown and the Jeremiah O’Brien.

To keep the shipyard workers housed, Kaiser bought 650 acres of farmland in the Columbia River floodplain, diked it and filled it with houses and apartment buildings. The place was first known as “Kaiserville,” then “Vanport.”

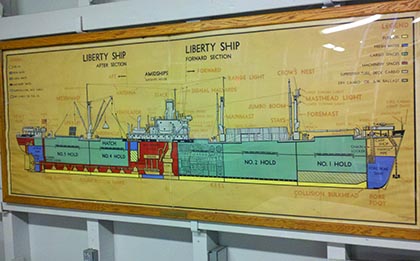

A chart showing the layout of a typical Liberty Ship, such as the Jeremiah

O'Brien, posted on a bulkhead on the historic ship.

(Photo: F.J.D. John)

Like the Liberty ships themselves, Vanport was not expected to survive World War II, but it did – for a few years, until a rotten railroad trestle washed out in a 1948 flood and let the river roar in. That flood was the biggest since 1894, and you can still today see the high-water mark on buildings in downtown Portland, where the water was two feet deep.

Longtime residents of Springfield remember when salvaged buildings from Vanport were trucked down the valley and set up there, shortly after the town washed away.

(Sources: Gulick, Bill. Roadside History of Oregon. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press, 1991; www.usmm.com (American Merchant Marines at War); www.ohs.org (Oregon History Project).)

-30-