The pirate-turned-railroad-man had big plans for Newport

Slippery rascal T. Edgenton Hogg, a genuine ex-pirate, hoped the little city would eat Portland's lunch with cheaper, faster passenger service to San Francisco, but two suspicious shipwrecks left him in financial ruins.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2017 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

By Finn J.D. John — December 1, 2009

Ah, Newport. Charming coastal town, endowed with some of the best crabbing and clamming, beach-prowling and lighthousing opportunities around.

But did you know that quaint little Newport nearly took over Portland's mantle as Oregon's major port city? And many people believe the only thing that prevented Newport from becoming the biggest city in Oregon — which, of course, would have totally transformed the mid-Willamette Valley — was a bit of dirty work done by Portlanders.

Here's the story:

This 1862 portrait shows Colonel T. Edgenton Hogg as he

looked during the Civil War. (Image: Oregon Historical Society)

[Larger image: 800 x 1067 px]

Introducing Colonel Hogg

After the Civil War, a fellow named T. Egenton Hogg — a hard-charging, big-dreaming former Confederate privateer — came to Oregon.

Hogg had nearly been hanged for his work during the war, and if that had happened Oregon history would have been deprived of one of its most colorful and endearingly rascally characters. He was, at one time or another, a pirate, a mariner, a jailbird lifer (in Alcatraz, no less) and a railroad baron. He was, it seems, always a swindler, forever working one angle or another.

Hogg the Pirate

During the war, Hogg and his squad of rebel pirates played fairly fast and loose with the line between privateering military action on behalf of the South, and outright robbery and piracy. When the neutral British quit trading with him for stolen goods, he hatched a new scheme to seize a steamship, put the stars and bars aloft and some guns below, and start robbing the opium ships that were then coming into California from China.

An 1875 lithograph image of Yaquina Bay by Wallis Nash. (Image: OSU

Archives) [Larger image: 1800 x 1304 px]

It didn't work. He got captured, and was at first sentenced to be hanged; then his sentence was commuted to life, and he was locked away on Alcatraz.

In 1866 he was released, though, along with thousands of other Confederate prisoners, in the general amnesty — and off he went to the new frontier, looking for new quasi-legal ventures that might make him rich.

Hogg the railroad baron

The business he settled on was railroads. At the time, the federal government was giving massive land grants to anyone who could punch a railroad through the continent, and he thought he might get hold of some of that. So he started looking things over very carefully, looking for an opportunity.

When he saw Newport, he immediately realized it made much more sense as a major seaport than Portland did. After all, to get to Portland you had to cross the Columbia River bar and spend an awful lot of time and fuel coming up the river. Moreover, using Corvallis instead of Portland as a rail hub would take 300 miles off the Chicago-to-Sacramento run.

Portland had made great sense when waterways were the only shipping routes available. Now, though, in the dawning age of the railroads, its location was a liability — or so Hogg thought. And perhaps he was right.

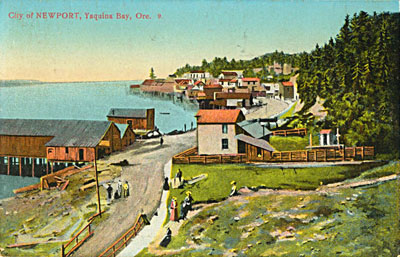

This postcard image shows the Newport bayfront as it looked in the

1960s. If Hogg's schemes had worked out, the city would be much

larger. [Larger image: 800 x 502]

In any case, Hogg saw the opportunity and went after it. He incorporated the Corvallis and Yaquina Bay Railroad Company in 1872, and a few years later he'd gotten started on a railroad line running from Philomath out toward Newport.

Portland businessmen strike back

Suddenly in fear for their economic lives, the Portland swells got busy. They bought up a band of property in Newport through which the new rail line would have to pass, then demanded enormous prices for them.

This hand-tinted postcard image from about 1920 shows the entrance to

Yaquina Bay. The railroad trestle covers the north jetty. [Larger image:

1800 x 1172 px]

Hogg responded by platting a new town further up the bay just outside Newport, calling it Yaquina City, and terminating his line there. Then he bought a steamboat, the S.S. Yaquina City, and started running passenger and freight service to San Francisco. With his completed rail line and a steamship at the end of it, his service made much better sense to folks in the middle and southern half of the Willamette Valley — and even some customers in the southern reaches of what's now the Portland Metro area — than going through Portland.

Disaster strikes ...

Now Hogg got busy at the other end of his railroad — the one that passed through Albany and was headed over the Cascades to the Boise rail hub.

The S.S. Yaquina City wallows in the surf after drifting aground at the

mouth of Yaquina Bay. The ship was a total loss. (Image: Salem Public

Library) [Larger image: 1200 x 885 px]

But while he was doing that, something awful happened. A nearly new steering cable on the S.S. Yaquina City broke at the mouth of the bay. The ship was washed ashore and broken to splinters by the surf.

The ship was insured. But it would take months to replace it, and Hogg needed the income or he'd go broke. He had just one hope: His contract with the government said that when he established service over the Cascades, he'd get a huge land grant that he could sell to raise the funds he needed. If he could just bamboozle the government out of that land, he'd be all right.

So Hogg quit working on his railroad and sent all his workers to the top of the pass. There, they built a line from nowhere to nowhere, crossing the mountains. Then a boxcar was hauled up by mules, assembled at the west end of the line, and pulled over the pass by the mules.

Having thus established a "railroad service" across the pass, Hogg reported success to the government. Which might have worked, but before it could, something else happened:

... and disaster strikes again

Hogg's new steamship, while being towed to Yaquina City, broke free from the tug – the cable snapped again! – and washed ashore to lay its bones right next to its sister ship. And this time, there was no insurance money.

Very few people thought the demise of two steamships, in the same spot, by the same mechanism, was a coincidence. Naturally, local thoughts turned to suspicions of sabotage by those Portland interests.

If those suspicions were true, the plot worked. No number of land grants would save Hogg now. He dropped his project and slunk out of the state, a ruined man.

But it's interesting to think about what Newport would look like today if he'd been successful, isn't it?

By the way, you can still see the rock cribbing where Hogg's desperation railroad was built, near the top of Santiam Pass.

(Note: I wrote an article very similar to this one, focusing on Hogg's "mule-powered railroad to nowhere" at Santiam Pass, for another publication. Click here to check it out.)

(Sources: Marcola-area historian Curtis Irish; Sullivan, W. Hiking Oregon's History. Eugene: Navillus, 2006; Sandler, Rich. The Rise and Fall of Yaquina City, a research paper written for Geography 422 at Oregon State Univ., 2008)