Bonus Army of 1932 started in Portland, ended Hoover's hopes

The most damaging single incident of the Hoover presidency started in Portland when Walter Waters started a peaceful march to Washington, D.C., to petition the president to let veterans draw on their service bonuses.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2017 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

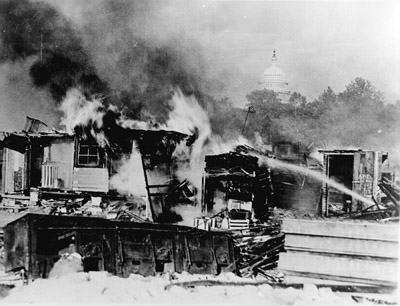

The makeshift shacks in which the Bonus Army marchers camped in

Washington, D.C., burn following the Army's crackdown on the move-

ment in 1932. (Photo: National Archives) [Larger image]

By Finn J.D. John — September 19, 2009

You may already be aware that the man who saved more people from starving to death than anyone else in world history spent his teenage years in Newburg and Salem. But did you know Oregon also supplied the seeds of his greatest defeat?

Oregon couldn’t have given young Herbert Hoover all the seeds of his future success, but it is certain that without growing up here, he would not have turned out the same man. Whether that man would have become president or not is one of history’s great unknowns.

But that’s not the only impact Oregon had on Hoover – or on the world as a whole. In fact, what many historians think is the single most damaging blow to his presidency – without which it’s possible he might have been re-elected in 1932 instead of losing in a landslide to Franklin D. Roosevelt – came out of Portland earlier that year.

The "Bonus Army" gathers in Portland

It was known as the Bonus Army. And it started when a Portland man named Walter Waters, a 34-year-old veteran of World War I, started a peaceful protest march on Washington.

He – like the thousands of other unemployed veterans who joined him on the way – wanted to be able to draw on his “bonus.”

The bonus was granted to veterans after the war, when Congress wanted to do something for them without actually paying for it – sound familiar? So they voted to commit to paying the vets a bonus in 25 years, around 1945.

Then came 1929. With the stock market crash came rampant unemployment. Some hungry, broke vets started thinking about that 1945 payout: Shouldn’t they be able to cash it out early, perhaps with a penalty, in their greatest hour of need?

No, said the government, which of course was having cash-flow issues of its own at the time.

And there things sat until Waters started his march early in 1932.

20,000 strong in Washington, D.C.

By the time Waters got to Washington, he was accompanied by 20,000 other veterans, all eager to petition Hoover for access to their bonuses.

That’s when Hoover made perhaps the biggest mistake of his political career: He refused to see Waters.

Denied an audience, Waters and his cohort started staging daily demonstrations and marches – peaceful ones – in Washington.

As the summer wore on, the marchers grew frustrated. Finally it became clear that Congress would not be cooperating. Some of the marchers started losing heart. Most of them, having nowhere to go, stayed in their makeshift camp in the capitol or in the empty federal buildings they’d occupied.

Finally, in July, Hoover made the second-biggest mistake of his political career: He called on the Army to get them out of town.

This was a mistake not so much because of the Army itself. The Bonus guys were veterans; they understood the Army. In and of itself, this was not that big a deal.

The real reason this was such a huge mistake was that in doing so, Hoover essentially handed Gen. Douglas MacArthur a blank check.

MacArthur behaving badly

MacArthur, who had convinced himself that the Bonus Army was a Communist uprising with very few real veterans in it, went about his task with gusto. Hoover, apparently realizing his mistake, ordered MacArthur to stop, but MacArthur ignored the command. Soon the Bonus Army was on the run, its shantytown was on fire and one veteran’s infant child was dead from tear gas inhalation.

But along the way, some very disturbing images were generated and disseminated on newsreels all over the country: Grizzled middle-aged men in ill-fitting Doughboy uniforms carrying American flags being pounded with the flats of soldiers’ swords, being cursed at and blasted with tear gas as MacArthur, in full dress uniform with medals and riding crop, rode around barking orders and preening. It was, most agreed, an unlovely scene.

The fury of an entire nation

The nation’s shock was hardened into outrage by MacArthur’s smug statements to the media, congratulating himself on a great victory over the forces of communism and anarchy. The marchers came from all over the country, and many Americans knew one or more of them. They weren’t buying the “bunch of communists” spin that MacArthur was trying to sell.

Hoover had no choice but to issue statements in support of his loose-cannon Army Chief of Staff and hope for the best.

But July 28, 1932, is generally accepted as the day Hoover’s last hope for re-election was demolished. It may also have been his last hope to be remembered fondly as an ex-president, for the majority of Americans alive at the time.

“I voted for Hoover in 1928,” one woman wrote to the Washington Daily News in response to the situation. “God forgive me and keep me alive at least ‘til the polls open next November!”

(Sources: Kingseed, Wyatt. “The Bonus Army War in Washington,” American History, June 2004; Alter, Jonathan. The Defining Moment. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007)

-30-