Did Oregon's biggest river save the world from Naziism?

Power from Bonneville Dam in 1930s was turned into warplanes, other aluminum war materiel in the 1940s; it also made the development of nuclear weapons and energy possible.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2016 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

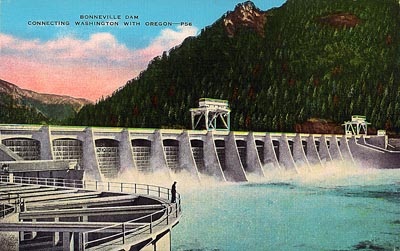

This postcard image of Bonneville Dam, viewed from the Washington

side, comes from a postcard dating from circa 1945. To see a larger

version of this image, click here.

By Finn J.D. John — November 9, 2008

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt launched the project to build Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams, he was thinking about jobs.

He had no idea those jobs would, a decade or so later, directly result in the world being saved from the machinations of the crackpot German chancellor — by making it possible for America and its allies to challenge and defeat the world's best air force and, quite possibly, by forestalling nuclear war.

All of that was in the unforseeable future, though, in 1933 when construction began.

Originally, the plan was to build just one dam on the Columbia River. The government settled on Grand Coulee, in Washington State. But the Oregon delegation in Washington, D.C., got very upset about this and begged Roosevelt to change his mind and favor the Bonneville site in Oregon.

Figuring two dams would create more jobs than one, Roosevelt gave the green light to both projects.

By the end of the 1930s, the dams were in service, churning out electric power that was basically free. (A side effect of this was the construction of thousands of homes in Oregon and Washington equipped with notoriously inefficient but easy-to-install electric ceiling heat — maybe you even live in one of them!)

It looked like a waste of money ...

But the two dams generated far, far more power than the U.S. could use in the 1930s. Especially the sparsely populated Northwest corner thereof. Transmission lines were built, but they could only take the power so far. And electricity can’t be stored — not in anything like an efficient manner. It has to be used the instant it’s created.

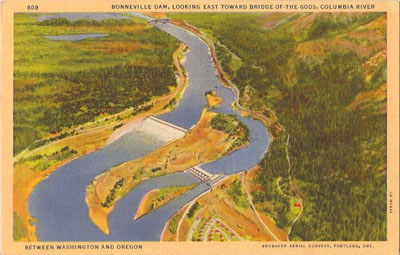

Another old postcard image, this one probably dating from before World

War II, shows Bonneville Dam from the air. [Larger image: 1200 x 764

px]

It looked like the main benefit of the dams was the thousands of jobs they’d created during the Depression. Two dams weren’t doing anything that one dam couldn’t have done, and even just one dam wouldn’t have done a whole lot more than a grid connection from Hoover Dam might have accomplished for a lot less money.

That is, until Dec. 7, 1941.

... then war broke out.

As you likely know, as the war went on America’s output of war equipment — especially airplanes — got bigger each year until the hapless Axis powers were completely overwhelmed with hostile (to them) tanks, planes and artillery. By 1945 the output was staggering, and it was topped off with a pair of war-ending nuclear bombings in Japan. The two Columbia River dams played a key role — an irreplaceable role — in all these things.

The seemingly unlimited electric power was just what America’s young aluminum industry needed. Airplanes and their armor were made from aluminum refined in plants very close to the dam; aluminum requires huge amounts of electricity to extract it from bauxite ore. And it’s no coincidence that Hanford, where the bombs used in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were built, is situated on the Columbia River near the dams — nuclear weapons research and production requires enormous amounts of electricity.

Could we have done it without them? Maybe not.

Perhaps these needs would have been sated without the two “job-creation projects” on the Columbia. Perhaps then Boeing and Douglas would have gotten their start somewhere in the Midwest, where airplane culture was so much more developed.

But also, perhaps — just perhaps — our production abilities would have fallen short of the challenge that was before us, and we would have lost the war. The Germans were chillingly close to developing a working nuclear bomb when they were forced to surrender in 1945; there's some evidence that they would have done so had it not been for some highly skilled Norwegian commandos who snuck in and blew up the Nazis' heavy-water refinery in 1943.

Furthermore, without all those aluminum airplanes flying over Germany and dropping bombs on factories and ore refineries, they might very well have beaten the Allies to it.

Did Roosevelt’s “make-work” project in Oregon save the world? We’ll never know for sure. But that's probably OK.

(Sources: Gulick, Bill. Roadside History of Oregon. Missoula: Mountain Press, 1991; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Publication EP870-1-42)

-30-