Did Japanese balloon bombs start Tillamook Burn?

We'll never really know. But the forest fire broke out in a remote spot at odd time of year, and to this day no cause has yet been found

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2016 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

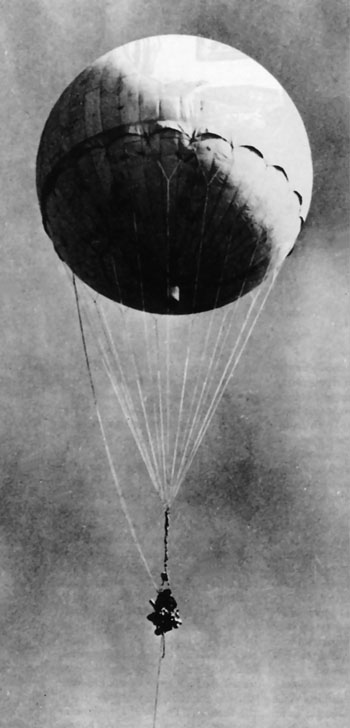

This wartime photo is a shot-down Japanese fire balloon that

was reinflated and photographed in California. [Larger image:

800 x 1665 px]

By Finn J.D. John — October 26, 2008

From where we sit today, it sounds like the craziest, most desperate play imaginable: Japan, locked in battle with the U.S. on various Pacific islands, floats bombs on balloons over the Pacific Ocean in an attempt to light the forests of Oregon and Washington on fire.

You likely are familiar at least with the basics of the story. Phosphorous bombs were attached to giant balloons made of waxed rice paper (one source suggests they were made using mulberry paper, but they were definitely paper) and launched on the prevailing winds, which blow across Japan and onto American shores.

As you may also have heard, this program claimed the only American lives lost as casualties of war in the mainland U.S. during World War II when a church picnic party found an unexploded bomb in the woods in 1945. It exploded, killing all but one.

What isn’t generally known is how sophisticated these balloons were. A balloon operates by maintaining a perfect balance between weight and lift: too much weight, no flight; too much lift, and you’re in orbit. So the balloons had sensors on board to monitor altitude. If the balloons got too low, weight would be dropped to get them back up off the sea again. There was also a clock aboard: at a certain amount of elapsed time, the machine aboard would pop the balloon and drop the bomb.

As you can imagine, such a level of complexity dropped the success rate well below 1 percent. Thousands of balloons were launched, at great expense, roughly $200 million, to score a few dozen strikes — on a howling wilderness. How could that possibly make sense?

Two words: Tillamook Burns. Remember, this program was launched in 1944. Eleven years earlier, in 1933, the first and most devastating wildfire broke out in the early afternoon of Aug. 14 in the Tillamook forest when a logging outfit in Washington County tried to snake just a few more logs out of an operation on Giles Creek. It was dragline logging, of course. The friction of one of the logs getting winched to the log landing heated some forest duff until it burst into flames, and by the time the autumn rains had come, 12.5 billion board feet of top-shelf old-growth timber was gone.

Six years later, in 1939, it happened again — started in almost exactly the same place, by the same cause. People started talking of a “six-year jinx.” The sixth year after that would be 1945. And, in fact, the forest did catch fire again on July 10, 1945, and again in July of 1951 — yep, that's every six years.

But the 1945 burn is particularly interesting. More than 200,000 acres of the old burn, and 30,000 acres of green forest, went up in smoke in 1945. It might have been put out faster, but America was still at war with Japan at the time, so there wasn't as much manpower available as there had been for earlier fires.

By July of 1945, the balloon-bomb program had been halted for a couple months already. Hard as it is to believe, the Japanese started the program just as the rainy season commenced in Pacific Northwest forests, and sent hundreds of would-be fire starters on their way across the Pacific Ocean all winter long — at a time of year when you couldn't start a forest fire if you had a thousand gallons of kerosene to do it with — then gave up on the program just as the sun started coming out and drying up the forest.

It's probably safe to assume that if the Japanese had started this program in April and continued it through October, rather than the other way around, history would be a little different, and the balloon bomb program wouldn't have been such a near-total failure.

But ... was it really a failure?

In marked contrast to the 1933 and 1939 burns, this blaze broke out very early in the fire season — in early July — and information about the source of this burn is hard to come by, for some reason. What is known is simply that it was near the Salmonberry River, a tributary of the Nehalem, in a spot that's virtually inaccessible.

Could it be that the Japanese balloon program actually did light the forest on fire, two months after the Japanese had given up on the plan as a failure? We'll probably never really know, but it's an interesting possibility.

(Sources: Gulick, Bill. A Roadside History of Oregon. Missoula: Montana Press, 1991; www.ohs.org; Love, Matt. Citadel of the Spirit. Pacific City, OR: Nestucca Spit Press, 2009)

-30-