COLUMBIA GORGE; MULTNOMAH, HOOD RIVER COUNTY; 1910s:

Scenic gorge highway set the tone for Oregon roads

No audio (podcast) version is available at this time.

By Finn J.D. John

|

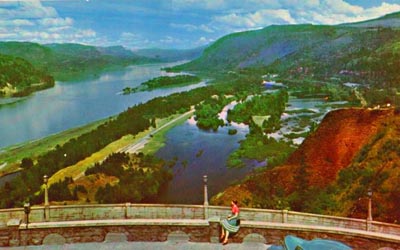

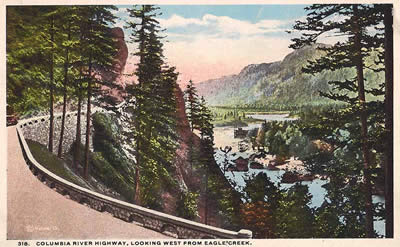

Everyone also knew the tourism potential of the Columbia River Gorge would be enormous. By now, most of Portland’s wealthy swells had outfitted themselves with automobiles, and the price of Henry Ford’s Model T had plummeted as he got his factory dialed in, to the point where most Oregon families could probably afford one. But Oregon’s dry summers and famously soggy winters meant that most roads would be pretty unpleasant to drive on most of the year. So, Hill hired Lancaster at his own expense to scout a route and draw up a plan. He scouted a route that threaded past waterfalls and scenic spots like the string in a pearl necklace — a “park to park highway,” as he put it several times. The road would be specially oriented to frame picturesque vistas, and it would harmonize with the scenery in such a way that Sunday driving motorists would find themselves immersed in the scenery — actually being part of the aesthetic effect, rather than just observing it. There would be long stretches of viaduct running right along the edge of the river, elegantly arched bridges spanning gullies and cliff faces, a spectacular windowed tunnel at Mitchell Point with views out over the water. Modern reinforced-concrete bridges would be faced with rocks carefully embedded to make the whole thing look like a rustic craftsman created it. Everywhere possible, drop-offs would be protected by a rustic stone-faced concrete guardrail, to stop cars from tumbling over the edge.

There was some resistance at first. One of the county commissioners dug his heels in, demanding that the project be narrower, uglier and cheaper, and demanding that some earlier less-thorough surveying work that had been done be built upon. Luckily, he was outvoted. There was also a good deal of trouble with the county surveyor’s office, where professional jealousy was given free rein, to the point where the commissioners finally decided to hand the whole thing over to the state to manage — Oregon had just formed a new state highway commission. There also were some property owners who didn’t want to play, or who were hoping to be paid more than their property was worth. Jennie Griswold, the owner of Multnomah Falls, demanded $50,000 for it ($1.6 million in modern currency). She settled for $5,250 after the City of Portland threatened to condemn it under Eminent Domain. (Here is a link to the Offbeat Oregon article about Multnomah Falls, and the Griswold family's plan to use it to power a sawmill.) In his account, C. Lester Horn tells of a Portland businessman whom he is careful not to identify by name. (I suspect it was Henry Wemme, the textile magnate who owned the first car in Portland.) But, whoever it was, he owned a business that did a lot of trade with hotels in Portland, including the Benson Hotel, owned by the highway’s number-one booster, Simon Benson. So Benson, after trying unsuccessfully to get the businessman to relent, canceled all his business with him. The businessman responded by promptly sending Benson a notarized easement to let the highway pass through the property. For the most part, though, most property owners didn’t want to be caught dragging their feet on a project that almost everyone was enthusiastically in favor of — both Portland newspapers, almost all Portland civic and business leaders, and a significant majority of Oregon taxpayers were all in. Most landowners donated an easement to the highway without even being asked to do so. Benson famously personally paid for the footbridge that crosses in front of Multnomah Falls personally. While chatting with Lancaster, Benson casually asked him how much he thought a bridge there would cost; when Lancaster came up with a figure, Benson wrote a check for it on the spot.

The scenic part of the highway was built between 1913 and 1915, but crews were still working on odds and ends until 1921 or so. It was, of course, a huge success, both as a conduit for freight and for tourists visiting the waterfalls. Also, it was the first paved highway in the northwest. By the 1930s, the freight hauling aspect had nearly taken over, and the highway was always clogged with heavy trucks. So engineers created a new highway along the water, designed for fast travel; this became, eventually, I-84. Meanwhile, the most scenic part of the old highway was preserved as a tourist route, so that folks could drive from park to park, the way Lancaster initially planned.

|