ASTORIA, CLATSOP COUNTY; 1940s:

Japanese sub blasted its way into Oregon history

No audio (podcast) version is available at this time.

By Finn J.D. John

|

Tagami knew the fishboats would show him the way through any minefields that might have been laid there, and any airplanes would be far less likely to spot the big sub in the middle of a group of obviously harmless targets. When the sub got within range, Tagami brought the sub to the surface with its deck pointed seaward so that it could scamper away to safety if things got sticky. Sailors scrambled out and got ready for action. The deck gun was deployed and limbered up and prepared for action. Then — wasting no time, because a submarine on the surface is the most sinkable ship on the sea — they cut loose. And for the first time ever, the state of Oregon was under direct attack by a wartime enemy. “We got off 17 rapid rounds of 5.5-inch shells from our deck gun, then raced out of there as fast as we could, leaving a wake of frantic fisherman,” recalled Warrant Officer Nobuo Fujita, the sub’s seaplane pilot, in an interview with the U.S. Navy’s Joseph D. Darrington in 1961. (I’m pretty sure he was joking about the frantic fishermen. The shooting started around midnight, by which time the fisherman would certainly have long since crossed the bar and headed for their home ports.)

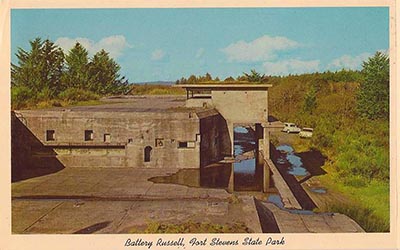

ON THE SHORE, “frantic” was also a pretty good word to describe the effects of the cannon fire. Frantic, that is, to get to the gun emplacements and return fire before the shooting stopped. Soldiers and officers leaped out of bed and started running around trying to get ready and go help return fire — in the dark, of course. People tripped over stoves and crashed into trucks and cursed at one another as they scrambled to their battle stations in their underwear. “We looked like hell,” Capt. Jack R. Wood, commander of the battery, told historian Bert Webber later. “But we were ready to shoot back in a couple of minutes.” They were ready, and itching to scratch their trigger fingers lighting up the sea around the enemy sub; but the orders were to hold their fire. This was for several reasons. First, struggling to use his rangefinder on a handful of muzzle flashes across the dark ocean, Capt. Wood concluded that the sub was out of their range. The big 10-inch guns, designed to stop ships from coming into the Columbia, would not tilt up high enough to lob shells to the attacking submarine. These guns dated from the “Endicott era” — roughly 1885 to 1905 — and had been designed to fire black-powder rounds. They were simply obsolete. The 12-inch mortars couldn’t reach it either, or so they believed. Nonetheless Wood requested permission to open fire. Major Robert Huston denied permission. Years later, he explained why in a letter to historian Webber: “I refused permission on this basis,” Huston wrote. “One: The submarine was not in range and was very likely firing a reconnaissance mission to spot location of our batteries. Two: The submarine outranged us by about 4,000 yards, being a modern 5-inch (approximately) gun on a barbette carriage. … Three: We had no radar at that time and we had to depend on visual observation of the flashes, or use searchlights, which certainly wasn’t advisable when you are outranged and the target is out of range.” As it happened, the target was not out of range … although it wouldn’t have taken the I-25 long to scoot back far enough to be safe. Playing a “what-if” game, though, if Fort Stevens had opened up with everything they had, all at once, aiming for the muzzle flashes, they would have had a pretty decent chance of blowing the sub out of the sea with the first or second salvo. For one thing, it would have been a huge surprise to the submariners to see the south bank of the river lighting up with cannon fire. Working with an old 1920s-vintage chart, Capt. Tagami believed the defensive works along the river were on the north side, well out of range of his boat. He also believed he was shelling a submarine base, not a full-on shore battery. When historian Webber actually met him in person, more than 30 years later, and showed him charts and pictures of the installation he’d been shelling that night, Tagami told him, “I feel more than lucky to be here tonight. I had NO IDEA there were such big cannon right in front of me.” But hindsight, of course, is always very clear. And the idea of a submarine cutting loose with a single relatively puny 5.5-inch gun in the dark of night made very little tactical sense ... unless ... unless ... Unless it was a recon mission. Shooting back might have made the crews feel better, but unless they got lucky with the first or second salvo, it would have revealed the guns’ position, relative size and range to a submarine that they were pretty sure was on a mission to acquire exactly that information. If so, the minute all the guns opened up, the sub would race away out of range, then go home and report that a nice big fleet of surface warships sitting 10 miles out to sea could pound Fort Stevens with impunity and then sail right up the Columbia River if it wanted to. Obviously, that couldn’t be allowed to happen. So Fort Stevens sat there, simmering with collective frustration, and took it — all 17 shells — without so much as a pistol shot in reply. And eventually, the I-25’s crew got tired of shelling the dark and unresponsive mainland, put the gun away, and left. Behind, they left the smoking wreckage of a baseball-diamond backstop, some slightly damaged power lines, and a handful of holes in the ground. The total dollar amount of damage done was probably well under $20.

|