ASTORIA, CLATSOP COUNTY; 1880s, 1890s, 1900s:

West Coast was the Detroit of fishboat engines

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

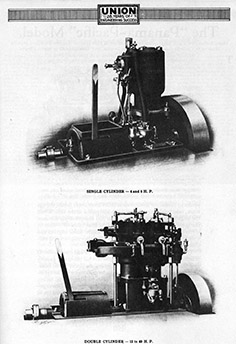

THE ENGINES THAT WENT into these old-school boats were slow, heavy, primitive, and built in one of several factories in San Francisco. In fact, until the mid-1930s San Francisco Bay was the Detroit of the marine-engine industry; the Union Gas Engine Company, est. 1885, was one of the very first manufacturers of gasoline engines of any kind in the U.S. These engines were installed on the open floorboards of the boats, uncovered. There were one- and two-cylinder models, ranging from four to 40 horsepower. Like an old John Deere tractor, they used a heavy flywheel to carry the momentum from one “pop” to the next, and they ran at very slow speeds — 350 to 500 revolutions per minute. But they made vast amounts of torque, so they could be fitted with enormous propellers — 24 inches was typical — and moved a lot of water when they were running flat-out. (As a side note, the Pescawah, the rumrunner ship whose crew was arrested after they ventured into U.S. waters to rescue shipwrecked sailors in 1925, was powered by a Union Gas Engine Company motor — one of the larger three-cylinder models, making 100 horsepower. More on that story here.) These old engines were much too primitive to have starter mechanisms or generators — or even magnetos. Each one came with a box of six ceramic jars and lids which the owner would fill with battery solution, and they provided the electricity for the engine’s ignition. To start one, a fisherman would open a little petcock on top of the engine and squirt in a little gasoline to prime it; then, he would pull a compression-let-off lever, retard the spark, grab the flywheel, and give it a leftward spin. Once the thing had fired two or three times, the fisherman would return the compression-let-off lever, advance the spark, throw out the clutch, and be on his way. It sounds complicated, but in practice it’s really not. Throughout the 1910s and 1920s — the high point of gillnet-fishing culture on the Columbia, before Grand Coulee Dam delivered its death-blow to the river’s salmon fishery — this was how it was done. But when people talk about “gillnetter boats” today, they almost always mean a different kind of boat entirely — the one that replaced the old double-enders starting in the late 1920s. These were the square-backed models known as “Bowpickers.” Bowpickers didn’t even give a nod to the old days of sail. They look somewhat like cabin cruisers, with a high-up steering station and a deckhouse covering the motor. And the best kind of motor for a bowpicker turned out not to be a big, heavy, slow-turning San Francisco dinosaur, but a smaller, lighter, fast-revving marine engine from one of the companies back east — like Continental or Gray Marine. And so the crude old West Coast marine engine fell out of use, and the factories eventually closed, and most of the engines they made got recycled for scrap metal during the Second World War. But every now and then you see one in a restored motor launch, or maybe in a marine museum — a reminder of the time when the West Coast was a marine-engine Mecca, and the Columbia River was swarming with salmon.

|

Background image is an aerial postcard view of Haystack Rock and Cannon Beach, from a postcard printed circa 1950.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2021 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.