FRENCH PRAIRIE, MARION COUNTY; 1850s:

Oregon’s literary legacy built on “true confession”

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

Unfortunately, even of this sorry lot, she picked a phenomenal loser: Dr. William J. Bailey of French Prairie.

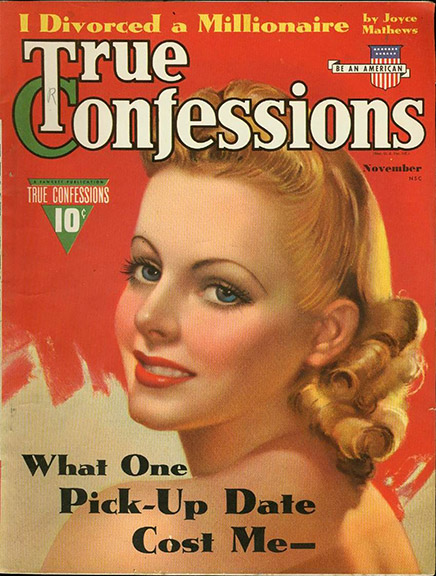

“I therefore leave you, resolved to live with you alone no more till I shall be satisfied that you are a reformed man. Besides the above, I am aware that you are nearly every day [word omitted from original, probably referencing a sex act] Indian women. And, after all this, to fear the horrid abuses and curses of such a profligate man as yourself, and at the same time perform every drudgery for him, I am certain that neither man nor God requires it of me. Signed, Your Suffering Wife.” It didn’t last. They were soon back together, and fighting became a way of life. During this time, though, the couple appeared to be doing very well indeed. Contemporary accounts report she kept their home immaculately clean, and played the role of the gregarious and mostly-respectable housewife very well. And in 1846, when the Oregon Spectator — the first newspaper ever printed in the state — got its start, she had a poem published in its very first issue, and for the next several months had charge of its “Women’s page.” Unfortunately, she feuded with the Spectator’s editor, C.L. Goodrich, and the matter came to a head when Goodrich published a particularly nasty parody of one of her poems that he may actually have written himself. This little feud would simmer between them for years, and would cause a good deal of bother for Margaret when her book was published. Meanwhile, things in the Bailey home were steadily getting worse. She stayed in the relationship and endured it as best she could for 15 years; but finally she secured a divorce and moved on. Or, rather, she tried to move on. Of course, this all went down at just about the time when the notoriety of Willson’s “confession” had died down. Now, in addition to that, Margaret was, as a matter of record, a divorcée, and this was almost as scandalous to 1850s Oregonians as being accused of fornication. Attempts to get back into teaching school were fruitless; mothers came and pulled their children out of her class after hearing the reports. Her divorce from Bailey had left her with some cash, along with her piano; but not enough to live on long-term. It surely also rankled Margaret to look at the progress William Willson, her fornication-accuser, had made in society. He’d married the “Other Woman” (the one he’d written to) and had what appeared to be a happy family with her, with three kids; he’d platted and founded the city of Salem; and he was revered as one of the officers of the provisional government formed at Champoeg in 1843. So Margaret decided she’d take the lemons life had handed her, and make a pitcher of lemonade. In lieu of sugar, she’d sweeten it with some nice strong vitriol, and set about feeding it to her enemies. The result would be a pseudonymous exposée of all the evils that had been perpetrated on her, and an account of how a good, pious girl like young Margaret could, through no fault of her own, end up as the Jezebel of the Oregon Territory. It would reveal the nasty, dishonest secrets that some of Oregon’s most revered “founding fathers” were hiding. And it would be very popular. People would read it with the same sort of furtive, wide-eyed fascination with which their great-great-great-granddaughters would peruse Fifty Shades of Grey. We’ll explore that fascinating, wonderful, awful book — the first book published as fiction in the Oregon Territory, the foundation of our state’s literary tradition — in next week’s column.

|

Background image is a hand-tinted linen postcard view of Three Sisters from Scott Lake, circa 1920.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2021 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.