WARM SPRINGS INDIAN RESERVATION; 1880s:

Ka-Ton-Ka patent remedy was Oregon’s own, sort of

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

To sell all this pseudo-Indian hokum, Edwards and McKay started out by hiring troupes to go forth and stage Wild West Indian Medicine shows around the country. And at first, the story of the Indians brewing medicine in the primeval forest proved a powerful lure. But their centrally controlled sales model didn’t scale fast enough to slake all the demand quickly enough to establish market dominance. Their main competitor in the Indian medicine racket, the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Co., promptly borrowed the concept and refined it into traveling Indian encampments (complete with painted tipis, a fast-talking bottle-waving “Indian Agent” to do the selling, and a bubbling cauldron of “medicine” that people could actually watch the “Indian medicine men” brewing). They literally hired more than 500 players — real Indians from any and every tribe, and Native-looking white people — to pretend to be Kickapoo Indians for these shows. They were peddling something called “Kickapoo Indian Sagwa,” a tonic almost identical to Ka-Ton-Ka.

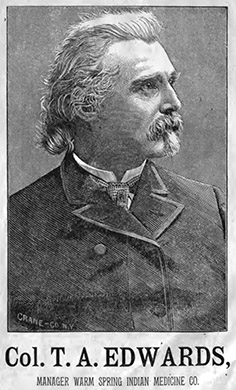

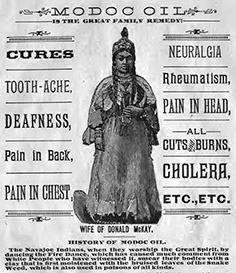

The cover of a pamphlet produced by the Oregon Indian Medicine Company, prominently showcasing Donald McKay and filled with pictures and feature stories about Warm Springs Indians, their customs, and their medicines; most of the stories, of course, were made-up. (To download the entire pamphlet as a PDF, click here.) (Image: Archive.org)Edwards decided that instead of meeting this challenge head-on, his company would instead corner the market on supplying independent medicine-peddler troupes with product to sell along with copious amounts of promotional posters and fliers, and let them do the work. He’d get a smaller slice, but there would be no central-office bottleneck to slow its growth. Soon all over the rural parts of the country, from the backs of special barouches and wagons and on the stages at community opera houses, in a thousand different ways, traveling medicine shows hawked Oregon Medicine. The idea of these shows was, basically, the same one that was used in the old single-sponsor early radio and TV shows like "The Chase and Sanborn Hour” or “The Camel News Caravan.” There would be copious entertainment — musical performances, sketch comedy, maybe a ventriloquist — followed by a pitch man urging everyone to get their wallets out. This, of course, was before radio or television, and many little towns that were visited by these traveling shows were so grateful for the entertainment that they would buy whether they felt they needed it or not. And it certainly didn’t hurt that Ka-Ton-Ka worked just as well as Tums to settle an acid stomach. It wasn’t truly useless — although it certainly wasn’t going to help syphilis sufferers, as the label promised, it was fine for “dyspepsia.” But it’s worth remembering also that in the late 1800s, traveling troupes of Vaudeville players had a terrible reputation, especially in rural communities. So many of them were fronts for gangs of card sharpers and prostitutes that the very name “Theatre” became poisonous; if you’ve ever wondered why the community theater building in towns like Elgin is called an “Opera House” despite likely never having hosted an opera in its entire existence, that’s why. Rural America is peppered with other “opera houses” for the same reason. But if a traveling Vaudeville company wasn’t welcome for moral reasons, a traveling troupe of healers selling medicine was fine. For one thing, one knew exactly what they wanted — to sell bottles — and didn’t have to worry about immoral hidden agendas; for another thing, if a troupe turned out to be a front for depravity, the company could be appealed to. So these elaborate sales pitches were giving rural Oregon, and rural America, something they didn’t trust anyone else to give them. Ironic as it sounds, the patent medicine swindlers were the only ones the public could trust, because they had made peace with that particular swindle. No one was going to go to Hell for having bought a bottle of useless medicine, but plenty of rural Americans would consider themselves or their loved ones in grave danger of damnation if they succumbed to the charms of a Vaudeville tart after a variety-theatre show. But over the first couple decades of the 20th Century, that changed. First, stock theatre troops like Baker’s Players in Portland started reclaiming the respectability of the stage; and then came motion pictures. By the outbreak of the First World War, not even the most straight-laced community had to resort to getting its entertainment from sales pitches. By then, the Indian medicine shows were already showing their age. McKay died in 1894, although his portrait stayed on the boxes till the end. Colonel Edwards died 10 years later. The company soldiered on, dwindling in size and changing hands several times, until it sort of faded away just before the First World War.

|

Background photo of the beach at Whale Cove was made by Bryce Buchanan in 2004. (Via WikiMedia Commons, cc/by/SA)

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2021 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.