PORTLAND, MULTNOMAH COUNTY; 1870s:

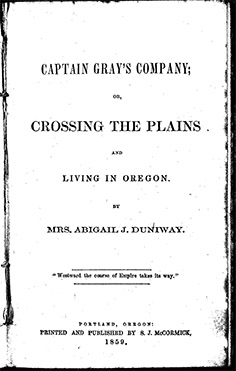

Abigail Scott Duniway considered self a novelist

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

In Ethel Graeme’s Destiny: A Story of Real Life, the entrepreneurial heroine is tricked into marriage by a drunken sea-captain who treats her like an ATM machine, leaving her penniless at the end of a life in which she’s made her fortune several times over only to have him show up and drink it all away. (Truth be told, this actually sounds like a slightly exaggerated version of Duniway's friend and fellow author Francis Fuller Victor's life, doesn't it? Here's a link to her story.) Edna and John: A Romance of Idaho Flat has a similar theme. Edna is swept off her feet by John, who turns out to be a callow idiot; while he’s off digging hopefully in the gold fields, she makes a fortune as a restaurateur, but when he returns and starts spending it frivolously and abusing her, she learns that if she divorces him, he will get everything: restaurant, money, and even the children. Meanwhile her mother, after being widowed, is kicked out of her lifelong home because the Dower Acts have enabled her husband’s creditors to seize all her property, and her aunt is left penniless after her late husband turns out to have been a bigamist. At the end, denied a divorce, Edna actually buys a gun; the story ends before we learn whether she uses it or not. Margaret Rudson: A Pioneer Story is less overtly subversive, but in other ways it’s more so. It’s the story of a wealthy heiress, who is also an inventor, entrepreneur, and physician, and her devoted fiancé. The two of them travel out West to found a socialistic commune in which men and women enjoy equality before the law and domestic chores — cooking, child care, cleaning, etc. — are shared equally by men and women and handled communally. Rudson and her fiancé — who come off somewhat like a 19th-century grown-up version of Nancy Drew and Ned Nickerson — get married, and adopt a hyphenated surname — Rudson-Horner — which was at the time considered a scandalously radical thing to do.

MOST OF DUNIWAY'S novels, particularly the ones serialized in The New Northwest, are a little rough, like second drafts. That’s because they were told in serial form over many weeks, like a soap opera; something interesting had to happen in every episode. This worked great in its original form, but the relentless procession of intense moments of drama can be wearying if read all at once; there’s a reason why no one binge-watches Days of Our Lives or The Young and the Restless. Also, Duniway didn’t always finish writing a novel before starting to publish it (actually, she may never have done that); so, sometimes she found herself boxed in by events of previous weeks and had to break the narrative thread to solve the problem. Still, they were very popular, and made more of a contribution to the campaign for women’s suffrage than most people realize. And to the women of Portland, in the late 1800s, they rang true to life, and they sent a strong and welcome message: You are not alone.

|

Background photo of the Yaquina Bay Lighthouse was made by LittleMountain5 in 2009. (Via WikiMedia Commons, cc/by/SA)

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2021 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.