LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM; 1914:

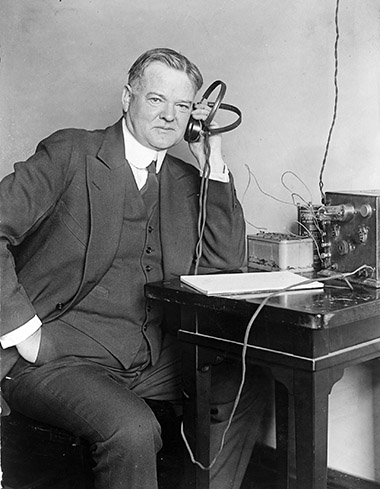

Hoover saved millions from starving to death

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

When the U.S. entered the war, President Woodrow Wilson named Hoover food administrator for the U.S. And after the war, Hoover became the head of the American Relief Administration and oversaw a program that kept another several hundred million from starving in Eastern Europe — and postrevolutionary Russia, a country run by the Bolsheviks, whom Hoover detested. All of this turned Hoover into an American hero. Throughout the 1920s, he was possibly the most admired American citizen, both at home and around the world. That popularity, of course, carried him straight to the top, and in 1929 he was sworn in as President of the United States … and then the Great Depression broke out. Just four years after he took office, Herbert Clark Hoover was probably the most hated person in America. The fact that Hoover, the man who essentially invented modern industrialized hunger relief, became associated with hunger and want in Depression-ravaged Americans’ minds, suggests that history has a dark and ironic sense of humor.

THE SHADOW CAST by Hoover’s failed presidency still haunts his legacy to this day. He is the president most often called upon for disparaging comparisons with sitting leaders — both George W. Bush and Barack Obama were compared with him by their opponents, and Donald Trump likely will be as well. Perhaps that’s why, other than the Hoover-Minthorn House in Newberg, Hoover's time in Oregon is barely noticeable. His home in Salem is now a private residence, and has been remodeled so that it no longer resembles what it looked like in 1890; its current occupants may not even realize they are living in a former President’s boyhood home. His office at the Oregon Land Company is now part of the building that houses the Union Gospel Mission. The Salem meetinghouse of the Society of Friends (Quakers), where he remained a member until his death, has passed into the hands of a new congregation from a different denomination. All that remains is some graffiti which he reportedly carved on a brick wall at the building that’s now Boone’s Treasury. In Shedd, though, if you visit the historic Boston Flouring Mills — now a state park — and take the guided tour, they’ll show you a color photocopy of a very old document. It’s a bill of sale dated 1891, facilitated by the Oregon Land Company; and one of the witnesses signed his name “Bert Hoover.” That was in 1891. Twenty years later the mill was running 24 hours a day grinding flour for Hoover’s American Relief Administration, which was using it to save several hundred million Volga Russians from starving to death … and chances are, no one working at the mill had any idea.

AN AGING HOOVER was called out of retirement after the Second World War ended, when President Harry Truman asked for his help in coordinating food relief to war-torn Europe. Hoover didn’t have to be asked twice. For several years after the war’s end, Hoover’s organization was the primary source of calories for hundreds of millions of Eastern Europeans. How many of them would have starved to death without Hoover’s help? We’ll never know. But Hoover himself, looking back on his life while writing his memoirs, estimated his total tally of lives saved at 1.4 billion. That’s roughly five times more deaths prevented than Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin, and Mao Zedong caused — combined. Whatever his reputation from the presidential years, Herbert Hoover was a man whom Oregon should be very proud to claim as a native stepson.

|

Background photo is an image of Highway 395 on the shores of Abert Lake, made by F.J.D. John in 2016.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2018 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.