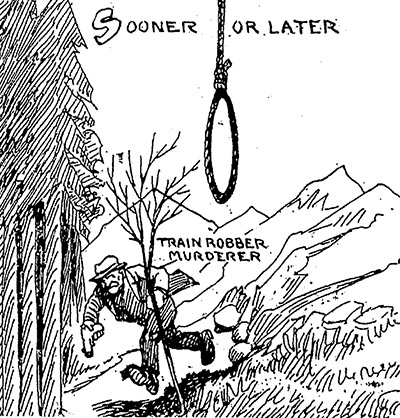

SISKIYOU PASS, JACKSON COUNTY; 1923:

‘Last great train robbery’ was brutal, clumsy fiasco

Audio version: Download MP3 or use controls below:

|

THE HEIST STARTED at the summit of the Siskiyous, as the train crossed the border into Oregon. It had to slow at the summit for a brake check just before going into a long tunnel — Tunnel 13, coincidentally enough — and when it did, Roy and Hugh jumped aboard the engine. Wasting no time, they leveled their weapons — a sawed-off shotgun for Roy and a .45 automatic for Hugh — and ordered the engineer, Sydney Bates, to stop the train right at the end of the tunnel. This was, it seems, to prevent passengers from seeing what was going on. (Ironically and tragically, it was to be Bates’ last day on the job; he was scheduled to start his retirement the very next day.) Once the train was stopped, the brothers were joined by Ray, who had been waiting at the end of the tunnel with a box of dynamite stolen from a mining operation, just in case it might be needed to open the mail car. As it turned out, it was needed for that. The mail clerk, when he saw what was happening, barricaded himself inside the car and refused to open the door; so the brothers packed dynamite around the door and touched it off. Unfortunately they had no idea what they were doing. The amount of dynamite they used wrecked the end of the car, filled it with smoke, and instantly killed the mail clerk, Elvyn Daugherty. And although they were now able to get in, it didn’t do them much good; there was mail scattered everywhere, they couldn’t see through the smoke, and the fire was spreading quickly. Back in the train, of course, the passengers were starting to panic. The train had stopped suddenly while they were still in the tunnel; then a huge explosion had rocked the car and probably broken out some windows, and the tunnel had started to fill with smoke and fumes. They were trapped in the tunnel like rats. One of the train’s brakemen, C. Coyle Johnson, started fighting his way through the smoke and flames to the front, trying to find out what was wrong. Unfortunately for him, he made it. Emerging from the fiery tunnel mouth, he startled the robbers, who wheeled and opened fire on him. Down he went, dead. At this point, the brothers apparently switched their plan from “salvage something from this mess” to “escape at all costs.” They ordered engineer Bates and fireman Marvin Seng to uncouple the engine from the mail car, apparently planning to have the engine take them down the mountain away from the scene of the crime; but the explosion had damaged the couplers, so it could not be done. So the brothers simply gunned the two survivors down in cold blood. Sydney Bates and Marvin Seng were simply shot in the head as they stood there with their arms in the air, because the brothers wanted no witnesses left on the scene. And then they ran, dragging creosote-soaked sacks behind them to fool the bloodhounds.

THE BROTHERS HID out in a cabin in the woods for about a week and a half, waiting for things to settle down a bit. While they were hiding out there, they noticed an unusual amount of activity in the air; in 1923, very few airplanes were actually in operation, but it suddenly seemed like every plane on the West Coast was flying low over the Siskiyous. But they didn’t figure out what those planes were doing until Roy hopped a freight train to Ashland to pick up some supplies. Sitting in a diner with a cup of coffee and a newspaper, he looked down and saw a photograph of himself and his brothers there, on the front page. The manhunt was on. It had been on since a few days after the robbery, when authorities had turned to a university professor for help in figuring out who the robbers had been. And it was in the course of that manhunt that the modern science of forensic detective work was born. We’ll talk about all that in Part 2 of this story, next.

|

Background photo is an image of Highway 395 on the shores of Abert Lake, made by F.J.D. John in 2016.

Scroll sideways to move the article aside for a better view.

Looking for more?

On our Sortable Master Directory you can search by keywords, locations, or historical timeframes. Hover your mouse over the headlines to read the first few paragraphs (or a summary of the story) in a pop-up box.

... or ...

©2008-2017 by Finn J.D. John. Copyright assertion does not apply to assets that are in the public domain or are used by permission.