Chinese smuggler saved woman and her baby, then vanished

In Gold Rush-era Oregon, the most skilled miners were probably the Chinese — but they were in constant danger. To avoid being robbed, they entrusted their gold to professional couriers who masqueraded as penniless vagabonds. This is a story from the life of one of them, a man we know only as 'Cheng.'

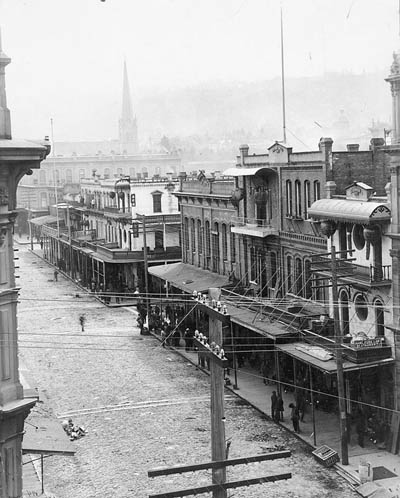

This 1890s-era photo shows Chinatown in Portland, near the intersection

of 2nd and Alder. This would have been one of Cheng's primary

destinations when retrieving gold from the mines; once in a major port

city's Chinatown, he'd be able to send the gold back to China or exchange

it for supplies, according to the instructions he'd been given when he

picked it up. (Photo: Friends of Portland Chinatown,

www. pdxchinatown.org) [Larger image:1200 x 1494]

By Finn J.D. John — March 5, 2011

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

Cheng was on his way to a southern-Oregon mining outpost one evening, during the heyday of the California Gold Rush, when he saw the wagon. It was slumped down in the road, hunched over a broken axle. But it obviously had only recently been abandoned; its canvas cover was still in fine shape. It would make a good shelter for the night, he thought.

He pulled open the flap. A terrified scream rang out. Peering inside, Cheng saw a starving, frightened woman holding a tiny newborn baby.

She soon calmed down when she saw that her visitor was just a mild, unassuming Chinese man, dressed in rags. Cheng did not look in the least bit dangerous. He didn't look like much of anything, really. That was the secret of his success, and probably the reason he was still alive.

The good Samaritan

Cheng opened his bag and started pulling things out. Food, of course, was the first order of business. But Cheng also had a wide assortment of herbs and extracts used for traditional Chinese medicine, so he brewed up a strengthening decoction for the woman and her baby.

They would need their strength to get out of the predicament they were in. Their wagon axle had broken a week before, and the woman's husband had taken the horses and set out to find help. There had been no sign of him since. Why he had taken both horses, instead of just one, wasn't clear; perhaps he wanted to avoid drawing attention to the wagon with his little family inside.

In any case, they couldn't wait for him. So as soon as the woman had her strength back, Cheng guided her to the nearest town. He stayed just long enough to make sure she was safe there — staying with the local stabler's family while waiting and hoping for her husband to be found.

Vanished

Then Cheng disappeared into the night like a phantom. The last thing he wanted was attention of any kind, good or bad. If he stayed in town, he could count on both — gratitude for saving a life mixed with suspicion that he'd had something to do with the husband's disappearance. It didn't matter. Any kind of publicity could be deadly for him.

The historic Chinatown Gate as it appears today. Today's Chinatown is

in a different part of Portland than it was in Cheng's time.

(Photo: ajbenj,

Wikipedia.org) [Larger image:1200 x 900]

Cheng was a courier for the frontier Chinese community. During the Gold Rush, as many as 20 percent of miners in southern Oregon and northern California were Chinese. They worked the rejected tailings of less patient miners, getting surprising amounts of gold out of them. They tried to be as inconspicuous as they could, and they lived in little segregated camps in the field, hoping a combination of invisibility and numbers would help protect them from drunks, bullies and robbers.

And they needed all the protection they could get. In frontier American society, the law offered them almost nothing. In theory it treated all alike, but in practice it covered Chinese immigrants only barely and in the most egregious cases. A murder here, a robbery there — few non-Chinese people cared, and that included sheriffs and judges.

So Chinese miners couldn't just pack up their gold dust and ride to Portland to buy things with it; they were too tempting a target. To get their gold out of the field, and buy things they needed — Chinese herbs, exotic dried seafoods and vegetables, even opium — they turned to professionals like Cheng. Cheng was part of an elite group of what you might call blockade runners. In effect, he was a smuggler — just not an illegal one.

How Cheng ran the blockade

On a visit to a camp, Cheng would pick up the miners' gold and bring it to one of the two major Chinatowns — San Francisco and Portland. There, the gold would be handled by trusted shopkeepers — divided out on different miners' accounts, sent home to family members in China and used to pay for supplies. Cheng would then return with the supplies. It was on such a trip that he came across the starving woman.

To safely deliver such valuable cargo took a special kind of skill.

Inconspicuousness key to survival

"He was very cautious," Cheng's descendant, Dave Cheng, told magazine writer Robert Joe Stout in an interview, "and never wore good clothing or let on in any way that he was carrying thousands of dollars concealed among his rags."

The younger Cheng, a San Francisco resident, told Stout his ancestor made a point of not paying cash for things on the way. He'd trade labor for what he needed, like a 1930s hobo — working as a deckhand to earn passage on a ship, or shoveling out someone's stables in exchange for permission to sleep in them for the night.

A lost frontier history, shrouded in secrecy and lost in the fire

And Dave Cheng's memories of family stories are probably the best documentation we'll find of the exploits of his remarkable ancestor and his colleagues. The fires that broke out after the 1907 earthquake hit San Francisco's Chinatown especially hard, and most of their records are now lost.

We still don't have basic information about how many Chinese people there were on the West Coast — or what they were dying from. It's possible that entire pogroms were carried out in the hills of gold country and no one knows about it today. It's also possible — almost certain, in fact — that many more deeds of heroism and compassion done by Chinese pioneers have been utterly lost to history.

As for the woman in the wagon, her fate has mostly been lost to history too. But through discreet inquiries Cheng was able to learn that her husband never reappeared; she finally gave up and moved with her baby back to Tennessee with her parents.

(Sources: Stout, Robert Joe. “The Chinese Mail Service,” Little Known Tales from Oregon History: A Collection of 28 Stories from Cascades East Magazine. Bend, Ore.: Sun Publishing, 1988; Minnick, Sylvia Sun. “Never Far from Home: Being Chinese in the California Gold Rush,” Riches for All: The California Gold Rush and the World (ed. Kenneth Owens). Lincoln, Neb.: U. of Nebraska Press, 2002)

TAGS: #PEOPLE: #heroes :: #MYSTERIES: #lost #legends :: # #cultureClash #race-#eastAsian #misunderstood #luckyBreak #underdog :: #116