Oregon embraced Carnegie Libraries like no other state

Of the 32 towns in Oregon offered a grant to build a library, not one failed to raise its matching money; no other state was as successful.

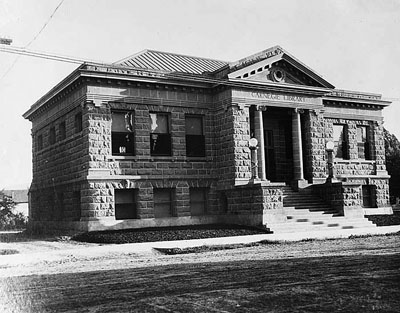

Downtown Albany's public library, built in 1911 with a Carnegie grant

of $12,500, is still in use today, although it's been augmented with a

larger and more modern library across town. Anyone who's familiar

with Carnegie libraries will instantly recognize this as one of them, based

largely on its dignified, symmetrical design in brick with a stairway

leading up the center into a second-floor entrance; although Carnegie

libraries come in a wide variety of styles, the similarities resulting from

the Carnegie Corporation's planning-and-layout “suggestions” resulted

in some distinctive and noticeable patterns that most of them share.

(Photo: Finn J.D. John) [Larger image:

1800 x 1015 px]

By Finn J.D. John — Sept. 25, 2011

If you walked into a city library in the 1880s, chances are you wouldn't even recognize it.

First off, if you were under 12 years old at the time, you wouldn't even be let in the door. Children were simply not allowed in.

But if you were of the appropriate age, what you'd find is a room with chairs and a desk and, usually, no windows. Behind the desk would be a librarian. You would have to know what book you wanted, so that you could ask the librarian for it; at that point, a library clerk would scurry back into the “Book Hall” to retrieve it.

The Book Hall was a massive room with walls formed in alcoves, to maximize shelf space. The bookshelves were two stories high, with a little balcony running around it for the clerk to access the second story's books.

The whole vision of a library, in those years of expensive vellum volumes and great social inequality, was as a treasure house of books, which must be protected from pilferage by an untrustworthy public. Today's vision of open stacks with borrowers freely browsing through the collection would have horrified a 19th-century library architect.

This postcard image of the Medford public library shows the distinctive

architectural signatures of a Carnegie library: central entry with stairs,

main floor above with a basement area below. [Larger image: 1171 x

746 px]

Libraries back then were not designed with the poor, hard-working immigrant in mind. Libraries sought to serve the sort of folks who, with a straight face, habitually referred to themselves as “the better class of people,” the sort who valued great literature — or, at least, valued being seen with great literature.

A literary revolution: Books for everybody

But in the twenty years after 1890, this vision of the library was utterly transformed. The average American city library went from a dark, secretive and magnificent palace like a necromancer's hall, to a light, open, egalitarian place in which everyone in town was welcome to come and paw the collection, in which a special area was set aside for children, with comfortable furniture and shelves anyone could reach.

A big part of this transformation was the spending spree Andrew Carnegie embarked on at about the same time — an industrialized program of library building in towns and cities around the world. And because it happened just as Oregon was starting to build its cities, it had a really big impact here. No fewer than 32 municipal libraries were built in the state with Carnegie money. On a per-capita basis, Oregon built more libraries than all but a handful of other states — roughly one library for every 2,500 citizens. And Oregon is the only state in the country in which not a single community that was offered a Carnegie Library failed to raise its matching funds and levy its maintenance-and-staffing tax (10 percent of construction costs, per year) to qualify.

Running philanthropy like a business

Baker City's Carnegie library, as seen circa 1940. Again, the classic

signature of a Carnegie design is evident.

(Photo: Oregon state library)

[Larger image:

1200 x 938 px]

Part of the reason Oregon in particular, and the western states in general, responded so well to Carnegie's library program is its basic egalitarianism. Actually, Carnegie revolutionized philanthropy with this program. Earlier philanthropists had taken a direct personal and paternal interest in their projects, making large and magnificent monuments to their own eminence in places they had a personal connection with and expecting gratitude in return.

Carnegie tried this — Carnegie Hall in Pittsburgh was built that way — but then threw the model aside and replaced it with an industrialized system. To get a Carnegie library built in your community, you didn't come to the big man himself with cap in hand; you submitted an application to his staff, people who didn't know you and didn't want to know you, whose job was simply to evaluate your city's application. It did not, in theory, matter if you were from the most prominent family in town, or had just stepped off a boat from Sicily.

Resistance from the self-proclaimed patricians

What's not to like? Well, in a number of more easterly states, this approach caused problems. The upper-class folks who formed local libraries' boards of trustees tended to prefer an older model, one in which the library included some built-in barriers to filter out “undesirable types.” A library could be a great place to go be seen cultivating one's upper-class appreciation for literature, if only those scruffy Polish or Italian or Irish immigrants and their unkempt children could be somehow kept at arm's length.

James Bertram, anti-snob

In response to this trend, Carnegie's secretary, James Bertram, became quite strict about library designs. Wastefully sumptuous meeting rooms for the trustees, excessively magnificent entryways, and decorative elements meant to impress were all one-way tickets to his “no” list. Wise towns studied the sample layouts he included with each application packet and built something very similar to something in it. And towns that were committed to the vision of a library as something to reinforce class distinctions either were turned down, or didn't apply.

Sure, that sort of snobbishness was a problem in Oregon too. But the state was young enough that many of its wealthy citizens still remembered what it was like to be fresh off the boat from somewhere with nothing in their pockets. Carnegie's goal of crossing class divisions with his libraries sounded just fine to them.

There were other reasons, too. Carnegie was a ruthless businessman; some of his methods had made him enemies. In general, the farther away from Pittsburgh a city was, the less likely it was to think of his gift as “tainted money” and refuse it on moral grounds.

Carnegie gave 90 percent of his pile

By 1919, when Carnegie stopped funding library construction, he'd given away $40 million of his pile. It was a relatively small slice of the total of $350 million that the guy gave away in his lifetime — which represented roughly 90 percent of his fortune.

In the process, he'd made educational materials and literature available to millions of people, especially children, in Western states like Oregon. Through Bertram's jaded eye, he'd helped transform the popular vision of a public library from the dark, intimidating temple of a hostile god into a bright, wide-open public square. And he'd probably made it possible for children in Oregon and other Western states to grow up and go forth and change the world.

(Sources: Van Slyck, Abigail. Free to All: Carnegie Libraries and American Culture 1890-1920. Chicago: UC Press, 1995; Oregon Library Association Quarterly, spring 1996; Long, James A. Oregon Firsts. North Plains, Ore.: Pumpkin Ridge, 1994)

TAGS: #PLACES: #structures #historic :: #PEOPLE: #progressives #doers #promoters :: # #culture #literature :: #148

-30-