Fish wheels making a comeback — to save fish

Once blamed for wiping out the enormous Columbia River salmon run, the mechanical salmon harvesters bring fish unhurt into waiting hands of conservationists who count, tag and release them

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2016 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

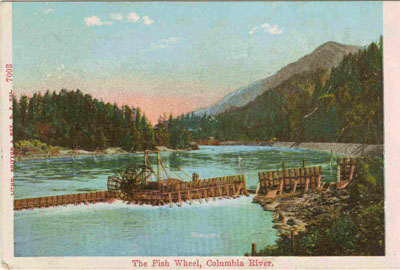

Another postcard image, of a fish wheel somewhere on the Columbia.

[Larger image: 800 x

540]

By Finn J.D. John — November 16, 2008

Fish wheels have a bad reputation. But they may be making a comeback — in a different role.

For about the last 10,000 years, Indian tribe members have taken big nets to bits of the Columbia River where the water runs fast and used them to scoop out salmon dinners.

When the industrialized Europeans came in the mid-1800s, they knew a good idea when they saw it. The Indians caught so much salmon, so quickly, that some enterprising Europeans quickly realized they could make a killing scooping out fish, canning them up and selling them cheap. But, not being inclined to stand around on fishing platforms as the sun beat down on them, they mechanized the method.

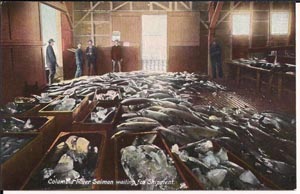

This old postcard image, also from around 1925,

shows an industrial catch of salmon ready to be

shipped. It's not clear whether this scene comes

from a fish-wheel processing facility or from a

gillnetting one. (For a larger image, click here)

And thus the fish wheel came to the Columbia. It’s sort of like a paddlewheel with baskets on the tips, with a wooden flume built downstream to divert a big cross-section of river into its path; the current turns the wheel, the baskets scoop out all the fish that are carried through the flume, and the cannery built nearby puts them all into little flat cans.

Just to give you an idea of how many fish these things scooped out of the river: One, built in 1887 about five miles north of The Dalles, pulled 418,000 pounds of fish out of the river in 1906 alone. By that time there were more than 75 others like it lining the shores of the river where it ran fast.

Meanwhile, fleets of gillnetters, based out of little fishing towns near Astoria, were also pulling vast numbers of fish out of the lower Columbia, where the water runs slow and deep, to be processed at canneries down there.

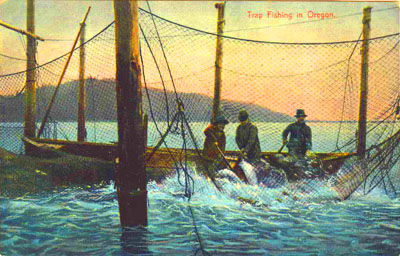

Fishermen pull salmon out of their fish trap in this early-1900s postcard

image. Trap fishing hasn't been practiced in Oregon commercially for

well over half a century. [Larger image: 1200 x 767]

Not surprisingly, the operators started noticing the catches dwindling as the early 1900s wore on. But their response was to blame each other for the fading of the fishery (no one yet realized it was actually a collapse they were dealing with, and perhaps it wasn't yet). The two groups – fish wheel operators and gillnetters – sponsored competing ballot measures in 1908, one banning fish wheels and the other virtually banning gillnetting. Both measures passed, but were blocked from enforcement by courts. Nice to see some things haven’t changed in 100 years, isn’t it?

Another postcard image, of a group of men working

a purse seiner on the lower Columbia. Again, the

date is roughly 1925. Note some of the men are

actually wearing neckties with their aprons. Seine

fishing is still done on the Columbia.

(For larger image,

click here)

By 1926, it was clear the fish were pretty much gone, and the state Legislature hastened to slam the barn door after the horse by banning the fish wheels. Gillnetters soldiered on; a greatly diminished fleet still plies the waters of the lower Columbia, but the catch is relatively paltry. A huge blow was dealt to the already suffering fishery a few years later when Grand Coulee Dam was built without fish ladders, cutting off a lot of fish from their spawning grounds. Today, most of the fish caught in the Columbia are raised in commercial hatcheries.

But the fish wheel may be due for a comeback. On the Okanagan River, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is using fish wheels to count fish, not can them. The baskets scoop juvenile fish out of the water without snaring or hooking them, and because it all happens so fast they don’t have much chance to hurt themselves flailing around in an underwater net. Once on deck, they can be logged, tagged with tiny electronic tags and sent on their way to the ocean, none the worse for wear – or, at least, not much the worse.

This old postcard, circa 1925, shows Indians

fishing for salmon at the Columbia River Cascades

near Cascade Locks. (For a larger image, click here)

It’s an interesting new, positive role for an old technology that many people think is responsible for a goodly share of the collapse of the biggest salmon fishery on the West Coast.

(Sources: OHS Oregon History Project; Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife; Northwest Power and Conservation Council)

-30-