Black sheep of the Union Army was Oregon’s last Civil War vet

Lebanon man lived a quiet, respectable life after the Civil War, but back in his youth he was a member of Olney's Detachment of the Oregon Cavalry — a Union Army outfit nicknamed “Olney's Forty Thieves.”

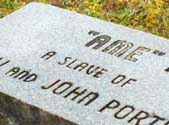

The grave marker of James W. Smith, Oregon’s last surviving Civil

War veteran, as it appears today in Lebanon’s IOOF cemetery.

(Photo: Randol B. Fletcher) [Larger image: 1200 x 868 px]

By Finn J.D. John — November 20, 2011

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

If you had told James W. Smith of Lebanon that people would one day visit his grave to pay tribute to his service in the Union Army during the Civil War, he might have laughed.

He might also have run for the door. The unit of the Union Army in which Smith served had a bit of a reputation. During their three-month operating career, before the Army wised up and disbanded them, Smith’s unit became known among regular Army units as “Olney’s Forty Thieves.”

Protection rackets and security theater

The story of the Forty Thieves company is an obscure one, and it hasn’t been studied much; there isn’t a whole lot of information about it out there. But what we do know is that it formed as a unit of 40 citizen-soldiers under the command of brothers Nathan and Orville Olney late in the war, in July 1864. Its official name was “Olney’s Detachment of the Oregon Cavalry,” and it was tasked with patrolling and providing security for important parts of the Columbia River Gorge.

This it may have, in fact, done. But it’s tempting to think the Olney Detachment’s real contribution to history was the invention (or at least, the refinement) of the art of security theater.

GAR Commander-in-Chief George H. Jones, left, talks to Theodore A.

Penland of Portland at the 77th GAR Encampment in Milwaukee, Wisc.,

in 1943. Penland became the GAR’s last commander-in-chief six years

later. (Photo: Richard Penland) [Larger image: 1200 x 1439 px]

Today, of course, a modern form of security theater is performed daily in hundreds of airports across the country, especially the ones equipped with Backscatter scanners. A stranger in an official-looking hat looks at images of you naked, talks to you like a New Orleans cop interrogating a murder suspect, and confiscates your toothpaste before letting you on the plane. The idea is to inconvenience you so much, you think the security guys are really on the ball, and quit worrying about the headline you read earlier this year about the loaded .38 Special that fell out of someone’s luggage at LAX.

The Olney Brothers were early adopters of a different form of security theater, which they practiced up and down the Columbia River Gorge. They had it working so that not only did it provide a pantomime of security-related action on their part, it paid nice financial dividends as well. Here’s how it worked:

At the time, Union Army soldiers enjoyed some of the finest clothing to be found on the frontier, including long, heavy blue wool coats that were much prized. The Olney boys developed a nice little scam in which the company would sell off its coats and other valuable Army stuff in one town, then go to another. There, they would claim to have just returned from action against Indians, in which all their supplies were seized by the enemy. Then they would send word to the Army that they needed more. They did this several times.

They also acquired a reputation for, as historian Randol B. Fletcher puts it, “fundraising” from the citizens they were supposed to be protecting. Surely we can’t credit the Olney company with having invented the “protection racket,” but it appears they weren’t strangers to the concept, either.

And this is probably why, in October 1864, at a time when the Union Army needed every man it could get hold of, it canned these 40 men outright. Some of them may have found their way into other military units, but Olney’s company as such ceased to exist eight months before the war itself ended.

Oregon’s star of the GAR

Now, let’s skip ahead to September 1950. The commander of the Grand Army of the Republic, Theodore A. Penland of Portland, has just died. The state of Oregon grieves the loss of what it thinks is the last surviving veteran of the American Civil War.

Penland was the kind of veteran that makes a state proud. As a lad of 16, in Illinois, he desperately wanted to join the Army and fight, but he wasn’t the kind of kid who can tell a lie and feel OK about it, so he was turned away twice when they asked him his age. Finally he actually wrote the number “18” on two pieces of paper and stuck one into each boot, so that he could tell the recruiter that he was “over 18 now.” That did the trick.

After the war, Penland moved out West and joined the Grand Army of the Republic, the exclusive Civil War veterans’ association. In the GAR, Penland distinguished himself as he’d never been able to in the actual Army. By the time he moved to Portland, in his 70s, he was already high in the organization’s rankings, a sought-after public speaker and radio personality who loved to talk about his experiences in the war and the time he saw President Abraham Lincoln.

In 1949, at the very last annual GAR meeting, the surviving members of the GAR voted Penland their commander in chief, a title he held until he died. So Theodore Penland of Portland was the last Commander in Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic.

When he died, the state of Oregon grieved, thinking it had lost its last Civil War veteran. But some time later, somehow it came to the state’s attention that it had missed one.

That’s right — Oregon’s last surviving Civil War vet was not the heroically active and patriotic Penland, but — not to beat around the bush too much — one of Olney’s Forty Thieves.

That would be James W. Smith.

Oregon’s last Civil War vet, for real

After being booted out of the Army with his comrades/co-conspirators, Smith had settled in Lebanon and lived a quiet, law-abiding life. He never applied for a pension; he apparently never even contacted the GAR. Perhaps he was embarrassed by the wildness of his youth. Or perhaps he thought he might have warrants. Who knows?

Smith died at the age of 108, six months later than Penland. And it took a while for Oregon to figure out its mistake. But on June 23, 2010, the Sons of Union Veterans officially rectified it when they gathered around his modest grave in the Odd Fellows cemetery and, in a graveside service including a musket salute, affixed a brass plaque to the stone identifying him as Oregon’s last Civil War vet.

It’s hard not to notice what a great metaphor Smith was for his home state of Oregon — wild and more than a little notorious in its youth, grown mature and mellow with age, but still with that old rascally twinkle in its eye.

(Sources: Fletcher, Randol B. Hidden History of Civil War Oregon. Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2010; The Lebanon Express, July 7, 2010; Sons of Union Veterans Website at www.suvcw.org; www.findagrave.com)

TAGS: #Topic148 #JamesWSmith #Olneys40Thieves #TheodorePenland #Lebanon #OregonCavalry #NathanOlney #OrvilleOlney #ColumbiaRiverGorge #SecurityTheatre #ProtectionRacket #GrandArmyOfTheRepublic #PresidentLincoln #SonsOfUnionVeterans #OddFellowsCemetery #RandolBFletcher #WILLAMETTEvalley #LINNcounty