Captain’s quick decision saved hundreds from a fiery death

Legendary riverman Uriah Scott had to choose between trying to save his steamboat and trying to save his passengers. He didn't hesitate for a second.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2024 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

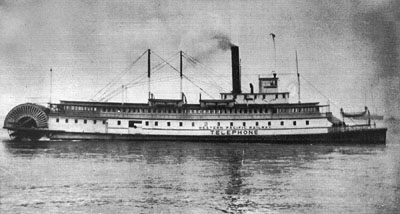

This photo from the 1800s shows the Telephone as it looked before

the fire. (Photo: Superior Publishing) [Larger image: 1800 x

759 px]

By Finn J.D. John — November 6, 2011

You might not think a fire on a riverboat would be that big a deal. After all, it’s only a river, right?

But fire on a riverboat was a very serious matter. The stories of paddlewheel riverboats on American rivers are peppered with tales of fires, and nearly all of them come with a body count.

Oregon’s most famous riverboat fire has a body count, too. It’s 1. But it would have been quite a bit higher had it not been for the quick thinking of its legendary skipper.

Here’s how it happened:

“Engine room’s afire!”

When launched in 1884, the sternwheeler Telephone was the fastest boat on the Columbia, and possibly the fastest in the country. With steam up, this rakish and palatial vessel could do considerably better than 20 miles per hour. Its owner, designer and skipper was the already-legendary Uriah B. Scott, the guy who brought true shallow-draft riverboats to the Willamette and later ate the lunch of Henry Villard’s would-be steamboat monopoly on the Portland-Astoria run with his other steamer, the Fleetwood.

The sternwheeler Telephone under way in San Francisco Bay, long

after the vessel caught fire on the Columbia; the entire superstructure

shown in this photo was built after the fire. The once-proud riverboat

ended up in San Francisco Bay as a railway ferry for a time before

being scrapped in 1918. (Photo: Superior Publishing) [Larger image:

1800 x

961 px]

The Telephone was even faster than the Fleetwood. And that speed would turn out to be vitally important on one particular voyage, on Nov. 20, 1887.

On that day, the Telephone was steaming toward Astoria as usual when Scott got a terse message over the speaking tube from the engine room.

“Engine room’s afire,” the engineer reported. “It’s driving us away from the engines.”

Stop and fight, or run for shore?

Scott had a choice to make, and he had to make it in the next few seconds. He could muster the crew and try to put the fire out, or turn and make for shore at top speed.

If he tried to fight the fire, he could possibly save the Telephone, a very valuable piece of naval architecture indeed. And, of course, if all went well, he could then continue to Astoria and deliver his passengers as usual.

But to do this, and have any chance of success, he’d have to kill the engines so that the wind created by the speed of the Telephone wouldn’t fan the flames. That meant that if firefighting efforts didn’t go well, they’d be stuck in the middle of the widest part of the Columbia River while the boat burned to the waterline and sank. Yes, there would be lifeboats in the water, but people would die. They always did. Decks collapsed under them, they became overcome with smoke, they panicked and jumped overboard and drowned, or maybe they died of hypothermia in the chilly November river water. There were 140 of them; some of them would die.

And if the crew lost the fight with the fire, the end would come fast. Riverboats like the Telephone were made, of course, of wood. That wood was kept carefully dry, to prevent rot, and usually pickled in varnishes and flammable paints which, even after they dry out, help the wood catch and burn (and make the smoke deadlier).

Captain Scott was an old riverboat man. He knew what happens when one starts to burn.

A worst-case scenario

He also knew what had happened to the Eliza Battle a couple dozen years before in Indiana. Efforts to fight that fire failed, and by the time the skipper realized he needed to make for shore, the rudder ropes had burned through and the boat could not be steered. Eighty people died on the Eliza Battle, and another 100 were badly hurt, while the boat blindly thrashed down the river.

If Scott opted to fight the fire, he might save the ship — or he might end up presiding over another Eliza Battle scenario and, if he survived, be forever haunted by the sense of having staked his passengers’ lives on a gamble to save his ship.

The alternative was to make for shore with all possible speed. This would involve sacrificing any possibility of saving the boat. The wind created by the Telephone’s speed would fan the flames to an inferno, and by the time the boat hit the beach, there would be nothing to do but watch her burn.

Then, too, it was not clear that the Telephone could make it to shore in time. The Telephone could hardly have picked a worse place to catch fire. It was most of the way to Astoria when this happened, and the river was almost five miles wide. Scott had a good two miles of open water to cross, and he had to do it before the fire spread enough to start killing people. Could he make it? Maybe not.

Captain makes his decision

Stay and try to save the boat, or run for shore and try to save the passengers? This doesn’t seem to have been a hard decision for Captain Scott. He didn’t even hesitate. “Put her full speed ahead!” he barked back into the speaking tube, and put the helm hard a-port.

The Telephone heeled over hard as the paddlewheel’s thrashing intensified, and Scott strained to hold the rudder over. Around the slim vessel came, until its nose was pointing straight at the state of Oregon. The engine-room “black crew,” having opened up the steam as wide as it would go, hustled through the smoke and fire to the top deck, where the passengers were already clustered around at the least fiery end of the boat —the one closest to shore.

From the pilothouse, Scott could look ahead at the patch of deck farthest from the flames, at the very bow of the boat, where the wind was sweeping the flames back and away. Soon everything behind and around his pilothouse was on fire. The rudder ropes had probably gone by now. In moments, the boat would be fully engulfed, and anyone still on deck at that time would start dying.

But he could see his gamble in making full speed for shore was going to pay off. The Telephone was going to make it in time.

Nobody was checking, of course, but it’s a safe bet that the Telephone was moving faster than it ever had before (or would again). In a few moments it would be connecting with the riverbank at 20-plus. The passengers packed into the bow braced for impact as best they could.

Then the Telephone fetched up on the Oregon side of the river traveling at maximum speed.

Passengers leap overboard

Luckily, there was a gentle mud flat there, and it buffered the impact. Still the Telephone dealt the state of Oregon a mighty blow, and passengers went flying to the rapidly-heating-up foredeck. There probably were some injuries; the record doesn’t say.

Whatever those injuries might have been, they weren’t enough to keep a single passenger on that by-now-dangerously-hot deck once the boat hit the shore. Over the gunwales they went, splashing into the water and mud and clambering up on shore to watch the Telephone burn.

The captain’s narrow escape

After watching the last of the passengers disembark, Scott turned to leave, but found to his consternation that the fire was surrounding the pilothouse and had burned away the steps. So he opened the pilothouse window and bailed out. Most sources say he executed a swan dive, but this seems unlikely given that the Telephone was stuck in mud. More likely, it was something on the order of a belly flop or cannonball.

The Telephone burned to the waterline as the passengers watched and firefighters from Astoria did what they could. When all was done, they found one single body in the wreckage — that of an unfortunate fellow who had just picked a really bad time to get drunk, and had either passed out or been too befuddled to find his way upstairs.

Everyone else made it.

The Telephone was rebuilt, and continued to work the Astoria run for many years after that. It enjoyed a reputation for blinding speed right up until it was scrapped, in 1918. But it was never as fast as the original Telephone was.

Luckily, it never had to be.

(Sources: Wright, E.W. Lewis & Dryden’s Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Portland: Lewis & Dryden, 1895; Newell, Gordon. Pacific Steamboats. Seattle: Superior, 1958; Marshall, Don. Oregon Shipwrecks. Portland: Binford, 1984)

TAGS: #EVENTS: #fire #shipwrecks #rescues :: #PEOPLE: #heroes #doers :: # #marine :: LOC: #clatsop :: #154