Coast Guard’s dramatic rescue saved ship — for Stalin’s most notorious gulag

Norwegian freighter got off course, piled onto Peacock Spit; a cutter pulled it off, and motor lifeboat crews rescued its crew, and the wallowing ship was pulled to port and repaired. A happy ending? Well, not for the Russians, it wasn't.

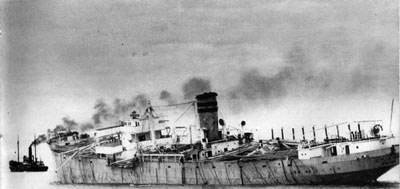

The 378-foot Norwegian freighter M.V. Childar wallows in the calm

waters of Puget Sound, to which she had been towed after having been

pulled off Oregon's Peacock Spit in a howling gale in May 1934. (Image:

Ralph Andrews/Harry Kirwin/Superior Publishing) [Larger image:

1800 x

850]

By Finn J.D. John — May 1, 2011

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

It was very early on the morning of May 4, 1934. On the bridge of the Norwegian cargo ship M.V. Childar, Captain Matthisen was noticeably — and uncharacteristically — nervous.

True, anyone would have been a bit on edge. His ship, a modern 4,100-ton diesel-powered freighter, was passing just off the mouth of the Columbia River — a notoriously dangerous place. And there was a full gale buffeting the ship from the southwest.

Still, Matthisen was an old salt. He'd slept through worse storms than this. What could it be that was bothering him today?

A moment later, a slight change in the sound of the sea made it perfectly clear. Instantly he knew the wind had shifted, and the Childar had blown off course — and that he and his crew were quite possibly about to die.

The sound he heard was breakers.

Shipwreck and disaster

By the time you hear breakers from the bridge of a 328-foot freighter, it's too late to do anything about it. Matthisen didn't even have time to yell before the Childar plowed onto Peacock Spit. A massive breaker sealed the deal by thundering down on its decks, now tipped at a crazy angle facing the sea.

Matthisen and his crew ran out on deck. The breaker had removed all the lumber stacked on the deck, along with one of the two lifeboats. The other had almost gone overboard as well.

Desperate to secure the other lifeboat before another heavy wave took it away, a half dozen crew members along with the first mate ran out to tend to it. While they were doing this, another massive comber descended on them and buried the ship in water and foam. When it receded, three men were missing, including the first mate; another was dead on the deck, crushed by the lifeboat; and three more were badly hurt. The lifeboat itself was smashed.

The Childar's surviving crew members were now stuck. Their only hope lay in an emergency radio call to the U.S. Coast Guard.

The rescuers

Unlike the Childar, the Coast Guard cutter U.S.S. Redwing was a steam powered ship, so it had to build steam before it could race to the rescue. So it was 11 a.m. before it got to the scene — four hours after the S.O.S. had first been transmitted. By now the Childar was in rough shape. Everything that could be swept off the deck had been — masts, cargo, pieces of superstructure. There was a big hole below the waterline, but the lumber in the hold kept the ship afloat. When the Redwing's commander, Lieutenant A.W. Davis, caught a glimpse through a momentary break in the fog, a massive breaker was sweeping completely over the stricken ship.

The Redwing tried to get a steel tow cable on the Childar, but the freighter had lost power and the winches were useless, and the crew couldn't manage the steel by muscle power alone. So a 12-inch hawser was launched with the line cannon, and a dozen men fought to muscle the massive waterlogged hemp line onto the bitts. Then the Redwing dragged her off the reef. The Childar floated wallowingly, listing to starboard, looking as if she would sink at any moment.

Motor lifeboats rescue the crew

Matthisen, however, said via radio that he thought the ship could hold together long enough to be towed to a port. However, the three injured crew members needed to get to a hospital fast. Could the Coast Guard manage to take them off?

It could. Two motor lifeboats were already on their way. One of them, the one coming from Cape Disappointment, was piloted by Chief Bosun's Mate Lee Woodward, who wasn't in much better shape than the men he was getting ready to rescue. A massive wave had boarded his boat and pinned him to the engine room bulkhead, breaking several ribs. Fighting through the pain, he pressed on.

The injured men were lowered on stretchers while the motor lifeboat pilots held their tiny craft steady alongside and crew members stood out on deck to receive their injured cargo. It's hard to overstate how difficult something like this is. A moment's inattention to the oncoming sea would have resulted in the boat being smashed against the side of the Childar, or drifting wide and losing the injured men into the sea. The engine had to be rhythmically and carefully managed to keep the boat from sliding down the sides of each wave as it came and went. But the operation came off perfectly, with both lifeboats.

Dragging the half-sunken ship to port

Then the Redwing started the long, arduous task of towing the stricken freighter to Seattle. There was no way it could be dragged across the bar into the Columbia with the seas so big.

It took several days to do it. The Childar had lost its rudder and did not want to track straight in the water; under the influence of the southwest wind it yawed out behind the Redwing and had to be dragged sideways through the sea. Halfway there it showed signs of breaking up, and most of the remaining crew were evacuated; then the Redwing almost lost the tow line when the bitts tore out of the Childar's battered deck.

As they inched their way up the Washington coast, the weather moderated. Then, around midnight on the last day, the Redwing got a wireless message from the Childar behind it:

"GOOD FOR YOU THINK WELL MAKE IT NOW," the apparatus beeped.

The following morning, the vessels were in the protected waters of Puget Sound, and the fight was over. Twenty-six mariners had been snatched from certain death and their ship, although heavily damaged, was saved as well.

Saved for a role in Stalin's holocaust

What the ship was saved for, though, was not so pleasant. After its repair, the Childar was eventually sold to a company from the small Baltic nation of Latvia, and when Josef Stalin's Soviets took Latvia over, the ship became Russian property. It was pressed into service as, essentially, a slave ship. In the years after World War II, more than a million people — political prisoners, mostly — were loaded on ships like the Childar (now renamed the Sovietskaya Latvia) and hauled to a place called Kolyma in northeastern Siberia, accessible only by sea, where Stalin's most notorious gulag was located. It was one of the biggest movements of humans by sea in history, and quite possibly the most brutal, its conditions rivaling the worst abuses of African slave ships in the 1700s.

In 1962, the aging freighter took its last voyage, heading to Kobe, Japan — where it was unceremoniously scrapped out.

(Sources: Bollinger, Martin. Stalin's Slave Ships. New York: Greenwood, 2003; Andrews, Ralph & al. This Was Seafaring. Seattle: Superior, 1955; Baarslag, Karl. Coast Guard to the Rescue. New York: Farrar, 1936)

TAGS: #DieselFreighter #Childar #ColumbiaRiverBar #Shipwreck #USCoastGuard #CaptainMatthisen #PeacockSpit #USSRedwing #AWDavis #LeeWoodward #Latvia #USSR #JosefStalin #SovietskayaLatvia #Kolyma #Siberia #MartinBollinger #RalphAndrews #KarlBeerslag #Rescue #COAST #CLATSOPcounty