Amateur pirates’ bumbling plan didn’t work out as they’d hoped

Two liquored-up Navy deserters planned to (a) seize control of a passenger liner; (b) drive it onto the beach; and (c) steal away into the night with three tons of gold. It's probably safe to say they didn't think their plan through very well.

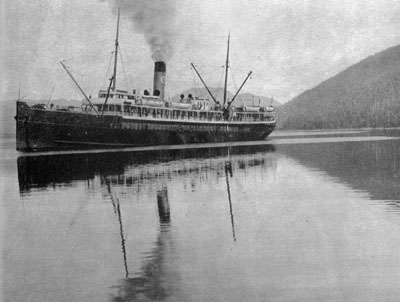

S.S. Buckman, later renamed the S.S. Admiral Evans, as she appeared

before the aft cabin was rebuilt. The ship still looked like this in 1910,

when the West-Wise piracy attempt was made. (Image: Superior

Publishing, "Pacific Coastal Liners.") [Larger image: 1700 x 1397 px]

By Finn J.D. John — April 17, 2011

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

It was probably the last act of piracy ever carried out on a commercial ship within American territorial waters — and it was a pathetic one. In fact, "piracy" may be the wrong word — it had a lot more in common with a couple clumsy freelancers trying to hijack a 727 than anything Blackbeard would have done.

Still, piracy it was, if Webster's New World Dictionary is to be believed. And what its perpetrators lacked in brains, they certainly made up for in ambition. Their plan was for the two of them to take over a 253-foot passenger steamer, run it aground and slip off into the woods with the $2 million worth of gold that they believed it was carrying.

This was a bad plan on so many levels and for so many reasons that it's hard to know where to start. Perhaps it's best to simply tell the story:

Sailor comes up with a plan

In the summer of 1910, thirty-year-old U.S. Navy sailor French West had come up with a plan. All he needed was a real good friend.

This photo postcard shows a wider view of the town of Yukutat, Alaska,

with the S.S. Admiral Evans docked at the cannery. The image was most

likely made on the same day as the more detailed view of the Admiral

Evans, shown above. (Image: Univ.

of Washington) [Larger image:

1200 x 759]

It seemed he'd found that friend in 26-year-old shipmate George Washington Wise, a sailor from Boston.

The idea was, the two of them would slip away from their ship — stationed in San Francisco Bay — and travel to Seattle, where they'd take passage on one of the big steamers that hauled the gold out of Alaska and down to San Francisco via Seattle.

Off the coast of Oregon, in the middle of the night, they'd storm into the wheelhouse and take over. Then, they'd put the helm over and beach the ship, hop overboard and disappear into the woods with the loot.

How could they have thought this would work?

This photo postcard shows the S.S. Admiral Evans, formerly known as

the S.S. Buckman,

docked at the cannery in Yakutan, Alaska, in 1923. In

the summer of 1910, this ship was the subject of perhaps the clumsiest

attempt at an act of piracy in the history of the universe. (Image: Univ.

of Washington) [Larger image: 1200 x 733]

Even making allowances for the benefit of hindsight, it's hard to imagine how West and Wise could possibly have thought this would work. The ship they had in mind was a huge, oceangoing passenger liner full of people who lived in Seattle. In 1910 Seattle was a frontier city awash with miners back from the gold fields in the Yukon and Alaska, many of whom carried .32 revolvers around in their pockets like we do cell phones today. Those passengers couldn't really be counted on to sit quietly by if they were to find out their ship was being jacked.

Even if West and Wise could avoid waking up the passengers, running a steamer head-on into the side of a randomly-selected piece of Oregon Coast scenery is like flipping a coin: Heads, you hit a beach and live (maybe); tails you hit rocks and die (for sure).

And if they won that coin toss, there they would be, on a strange beach in the middle of the night, trying to slip away from a couple hundred angry passengers plus whatever locals might be on hand — with $2 million worth of gold.

The Admiral Evans in dry dock, sometime in the 1920s. The colors are red

below the waterline; a green hull; white cabin and decks; and a beige and

black funnel. Looking at this image, it's easy to see another problem with

the would-be pirates' plan: The ship draws a good 15 feet of water, so

it would be a long and grueling row or swim to shore, past the breakers,

if they grounded it.

(Image: Superior Publishing, "Pacific Coastal Liners")

[Larger image:

1800 x 1310 px]

Two million dollars' worth. In 1910, gold was $21 an ounce, so $2 million dollars' worth was just a little shy of 6,000 pounds. Three tons of gold — a ton and a half for each of them.

Most likely they thought, as many did at the time, that the Oregon Coast was a howling and uninhabited wilderness, a great place for capital criminals to go for quiet time while on the lam. They would no doubt have been astonished at the number of well-armed local residents ready to welcome them, pretty much regardless of where they landed.

And finally, it's a minor point, but — take a look at the photo of the Buckman in dry dock, just above. The color change on the hull shows the waterline; notice the size of the workmen in relation to the amount of hull below that waterline. As you can see, even beached, the Buckman would be in water far too deep for the men to wade ashore. How would they get off the ship? Swim, through the surf? How would they get the gold ashore? Ingot by ingot perhaps, in a lifeboat, in the breakers?

Yes, it's probably safe to suggest that West and Wise didn't think the plan over very carefully.

The plan comes together, after drinks ... lots of drinks.

Still, in the wee small hours of the morning of August 21, 1910, there the two of them were, thoroughly braced with spirits and padding along the deck to the wheelhouse of the 253-foot, 2,000-ton passenger steamer S.S. Buckman, ready to give it a good go. The ship was about 20 miles off the mouth of the Umpqua River at the time.

What exactly happened next is a bit hard to know, because every account of the attack is different. But after reading them all, giving extra credence to eyewitness accounts in contemporary newspapers, I'd say this is probably pretty close to what actually happened:

The guns come out

West and Wise opened the wheelhouse door. Second Mate Fred Plath and Quartermaster Otto Kohlmeister looked up in alarm, and then the guns came out: a revolver in Wise's fist, and a sawed-off double-barrel shotgun in West's hands. Plath was ordered to stretch out on the deck, and Kohlmeister remained, hands on the wheel. According to Allyn, he was "cursing vigorously." Kohlmeister was ordered to put the helm over and head for the beach, and he complied.

Already there was a problem: The captain wasn't there. Leaving Wise to cover the two in the wheelhouse, West raced aft to the captain's cabin.

The captain is gunned down

The Admiral Evans sails through the protected waters of Alaska's Inland

Passage on a 1921 visit to Alaskan ports. (Image: Superior Publishing;

Pacific Coastal Liners) [Larger image: 1800 x 1630]

Captain Edwin B. Wood must have already known something was going on. One source suggests he was awakened by a heavy rolling of the ship, which would have told him the vessel had changed direction and was turning toward shore. Given what usually happens when a liner gets too close to the coast, it makes perfect sense that this would ring alarm bells in the skipper's head.

In any case, when West got there he found Wood reaching for a pistol. The pirate let him have it with both barrels. The captain died in his tracks.

Up in the wheelhouse, the gunfire startled Wise, and he poked his head out to see what had happened. One of his prisoners — most sources say it was Kohmeister — took advantage of this opportunity to yank the whistle cord. The liner's steam-powered whistle screamed a three-digit-decibel alarm. Now suddenly the whole ship was awake and wondering what was going on.

The No. 2 bandit loses his nerve

West, hustling back from the captain's cabin, arrived just in time to start collecting crew members. Like lobsters entering a trap, they would run into the wheelhouse to see what was going on and see West there with his guns on them (he had a revolver in addition to his shotgun). West would then order each newcomer to join the growing line of men standing by the bridge ropes.

West sent Wise to smash the radiotelegraph, knowing the on-board "sparky" was probably already warming the apparatus up. Wise, though, lost his nerve, and instead of doing this he ran belowdecks and hid.

This was pretty much the end of West's hopes for a profitable end to the venture. He had about eight crew members lined up in the wheelhouse facing his revolver and now-empty shotgun, and more crew members were coming up.

Then one approached from the other side of the bridge just as West was kneeling down to reload his shotgun.

The crew makes a run for it

"Seeing that our chance for escape was ripe, I yelled to the crew to 'run,'" Chief Mate Richard Brennan told the San Francisco Examiner afterward. "We all broke in different directions. For my part, I ran and jumped through the galley skylight, landing on the cook's hot stove."

Soon West was alone with Kohlmeister, who never left the ship's wheel the whole time.

First Mate starts shooting back

Meanwhile, Brennan was running to the captain's cabin, where he got out the dead skipper's revolver. Back to the bridge he skulked with it, and from the shadows about 10 feet away he opened fire, emptying the five-shot pistol (probably a cheap .32- or .38-caliber break-frame pocket revolver) at the bandit.

"He seemed to bear a charmed life, for not a bullet struck him," Brennan told the newspaper. "By this time the lone man was thoroughly scared. He ran back to the smokestack, but as he did so he let another shot go at me. That's the last time I saw him."

One bandit vanishes; the other is found crying in his bunk

Brennan, now the acting captain, ordered the engine shut off and all the lights doused, basically putting the whole show on pause until morning.

When the sun came up, Wise was found huddled in his bunk in steerage, whimpering to himself. He went insane before he could be tried, and was committed to an asylum.

Nobody ever found a trace of West; most accounts say he jumped overboard, but nobody actually saw him do so.

(Sources: Allyn, Stan. Top Deck Twenty: Best West Coast sea stories. Portland: Binford & Mort, 1989; San Francisco Examiner, Aug. 22 and 23, 1910; Portland Morning Oregonian, Aug. 22, 1910)

TAGS: #Offshore #Piracy #DumbCrooks #BumblingPirates #Hijacking #FrenchWest #GeorgeWise #Seattle #Klondike #Steamship #SSBuckman #AdmiralEvans #FredPlath #OttoKohlmeister #StanAllyn #EdwinBWood #RichardBrennan #Gold #COAST #DOUGLAScounty