Tiny home-built schooner saved Tillamook settlers

After the only skipper willing to brave their fearsome river bar died, the only way to get wheat and cheese to market was to build their own trading ship — which they did.

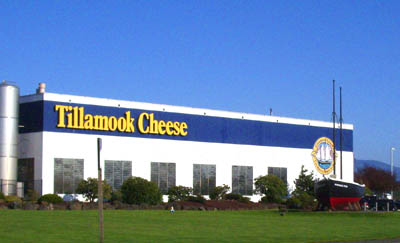

The little black schooner to the right of the Tillamook Cheese factory is a

replica of the ship Tillamook settlers built themselves so they could trade

with Astoria and Portland,

because no outside skipper would risk his ship

on their fearsome bay bar.

(Photo by EncMstr, Wikipedia.org)

[Larger image: 1800x1093]

By Finn J.D. John — February 27, 2011

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

If you’ve ever paid a visit to the Tillamook Cheese factory, you surely noticed the little black two-masted schooner permanently dry-docked in the parking lot next to Highway 101. But few people outside the little Tillamook Bay basin know the significance of this vessel.

Here’s the story:

In the early 1850s, a small group of settlers came to Tillamook Bay. They found the local Native Americans friendly and welcoming, the land fertile and green and the bay full of good things to eat.

The problem was, though, that getting in and out was very hard to do. Rugged, trackless mountains to the east bordered a band of wilderness 75 miles thick separating the Willamette Valley from the sea. The mountains to the north, blocking the path to Astoria, were even more formidable; a traveler on horseback could get through, but a buggy or wagon could not. And there wasn’t much reason to want to go south — not in the 1850s.

That left the west — that is, the open sea. But Tillamook Bay has a bar whose reputation wasn’t too much milder than that of the legendary Columbia River itself. Ebb tides in Tillamook Bay don’t pile up into 70-foot-tall freighter-killers like they do off Astoria, but they do get plenty rough, and in those pre-jetty days the sandbars could be tough to dodge.

Only one captain will brave the crossing ...

Still, one enterprising captain by the name of Means was willing to do it. Captain Means owned a small brigantine and a smaller sloop, and was skilled enough to brave the bars and bring things like coffee and milled flour into the bay to be exchanged for things like wheat and cheese.

Means soon figured out that he all but owned a trade that would probably soon be very lucrative. So he embarked on a plan to sell both his ships and build a steamer, with which he planned to go into business in Tillamook.

... but then he died.

Alas, Means died at just the wrong moment — after selling his sloop and barkantine, but before building the steamer. His death left all of Tillamook Bay effectively stranded, like a desert island. Of the tiny handful of captains plying the West Coast in 1853, none was willing to risk the trip.

Though the settlers had all the milk and cheese they could eat (and then some — after all, cheese was their main stock in trade), they soon had no sugar. Nor flour, nor coffee — they had to laboriously grind wheat kernels in their coffee grinders to bake bread, and they resorted to drinking a toasted-wheat beverage instead of coffee or tea. No one was going to starve, but life on a diet of cheese, boiled wheat and whatever roots and plants the Native Americans could spare was miserable, and they determined to do something about it.

So — they built a ship.

A 37.5-foot-long solution for the town

As pioneer Warren Vaughn later recalled, the project was started in late September 1854 with the laying of a 37.5-foot keel. The tiny community swarmed over the project, milling raw logs into dimensional lumber with a whipsaw and sealing the hull with pitch. Lacking iron to make fittings, the settlers trekked over the northerly mountains to scavenge the iron from the Shark, a 184-ton U.S. Navy sloop of war (actually a schooner) shipwrecked there in 1843, after whose deck artillery Cannon Beach was named. Local Native American tribes, happy to help their neighbors, salvaged a bunch of canvas, rope and more iron from another wreck to the south, that of the bark Oriole, and sold the whole lot to the settlers for $10 — a pittance even back then.

Three months later, on Jan. 1, 1855, a complete schooner — christened the “Morning Star of Tillamook” — was ready to be launched. After an initial unsuccessful attempt to launch it on skids greased with estuary mud, the settlers reluctantly sacrificed a steer to get the necessary tallow and to the sounds of cheers the tiny ship slid into the bay.

Back in business!

This image shows the Morning Star II under way, making its journey to

Portland with a cargo of six tons of Tillamook cheese on board, as part of

the state centennial festivities in 1959; the ship brought a load of products

for local stores back on its return. Axel Anderson of Bay City served as

skipper on this voyage.

(Photo: Tillamook County Library) [Larger

image: 1200 x 849]

And with that, Tillamook was back in business. Tiny as it was, the little schooner was big enough to solve the community’s problem, and in competent seafaring hands quickly proved Tillamook was a place worth trading with.

A year and a half later, the Morning Star was sold to an Astoria company, which then sold it to a shipping company in Olympia, Wash. Just a few years later, in 1860, it sank in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, near the San Juan Islands. But it had made its point, and from then on Tillamook never lacked for shipping. Residents never forgot it, and in 1959 a group of volunteers built a new one just like it — the Morning Star II — which they used to deliver six tons of cheese to Portland that year.

The schooner you see at the cheese factory today is another replica of the original, dedicated in 1992.

(Sources: Orcutt, Ada M. Tillamook: Land of Many Waters. Portland: Binford & Mort, 1951; Marshall, Don. Oregon Shipwrecks. Portland: Binford & Mort, 1984; Wright, E.W. Lewis & Dryden’s Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Portland: Lewis & Dryden, 1895; www.tillamook.com)

TAGS: #PLACES: #historic #structures :: #EVENTS: #economic :: # #badTiming #marine :: LOC: #tillamook :: #115