America’s first highway rest area

had marble walls

Legendary Crown Point Vista House looks out over the Columbia River and was the highlight of the Columbia Gorge Scenic Highway — built when roadbuilding was as much an art as a science.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2024 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

This postcard image shows the Crown Point Vista House, and the vista

after which it was named, in the 1930s. [Bigger image: 1800px]

By Finn J.D. John — December 13, 2010

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

THE NATION'S FIRST publicly owned rest area perches on the brow of a bluff just outside Corbett, Oregon, overlooking the most spectacular section of the Columbia River Gorge.

It’s called Crown Point Vista House, and it’s the jumping-off point for America’s oldest scenic highway — the Columbia River Highway.

This postcard image made shortly after the Vista House's dedication in

1918

shows what an early motorist driving to Crown Point would see.

The stone guardrail in the foreground was built by master stonemasons

brought from Italy for the job. [Bigger image: 2400px]

The Vista House is rather more than just a rest area. For starters, the bathrooms are finished in marble and mahogany. It was designed by a German architect and built out of cut sandstone at a cost (in today’s dollars) of roughly $2 million.

But then, the Columbia River Highway is more than just a road.

Eastern Oregon was snowed in — every winter

Today most people know this road as an old and scenic by-way, peppered with picturesque old bridges and tunnels and bejeweled with waterfalls and panoramic views but often clotted with motorhomes.

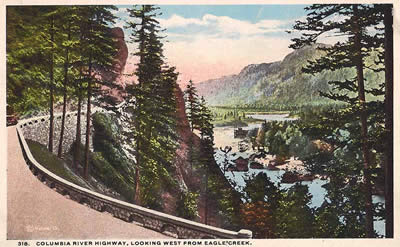

This postcard view shows the highway near Eagle Creek, with the river

beyond. A careful look reveals a sternwheeler in the river below.

[Bigger image: 1800px]

It’s hard to think of this, but in 1915 when construction started on this road, western Oregon might as well have been across an ocean from the rest of the nation for half the year. Steamboats plied the Columbia River and could take passengers to The Dalles, but passage wasn’t cheap and the river, untamed as yet by hydroelectric dams, was far from the broad, placid waterway we think of today.

Likewise, railroads ran up the gorge, but these weren’t cheap either, nor did they stop so passengers could look at waterfalls and picnic on river beaches along the way.

An early-1900s hand-tinted postcard view of the interior of the Mitchell

Point tunnel, a feature of the old highway of which its builders were

enormously proud. The tunnels are gone now, part of the highway

that was sacrificed for the Interstate 84 right-of-way. [Larger image:

1800 x 1137 px]

Your other option for getting out east was to hitch up a wagon and team of oxen (not an automobile – they didn’t have the traction) and set out on the infamous Barlow Trail, or head south to Springfield and over McKenzie Pass … just not in the winter or early spring, when the passes were covered in yards-thick layers of snow.

Rich people seek a nice place to drive

Enter philanthropist Samuel Hill. Hill had dreamed of a scenic route through the gorge for some time, and by about 1913 the stars were beginning to line up.

This picture postcard was probably created before the Vista House was

open to the public. The stonework seen here is the work of Italian

masons hired from overseas. [Bigger image: 1200px]

First of all, all the wealthy swells in Portland had bought themselves automobiles and were finding their usefulness frustratingly limited by the crude, muddy roads of the day. Many of these oofy motorists were willing, like Hill, to put their money and social influence behind a highway project that would give them a place to take their Buicks and Maxwells for Sunday drives and leisurely picnics – and to show off the unique qualities of what was still a pretty rough-hewn frontier city to upper-crust visitors from back east.

Increasingly, thanks to Henry Ford’s cheap iron, the less wealthy were joining them on those roads, and popular pressure to do something about the problem was building.

Sam Hill's scenic vision stirs

This early and rather poorly composited postcard (notice the car on the

left has been pasted into the picture) gives an excellent impression of

the Portland elite's vision for the Vista House. [Bigger image: 1200px]

For help with his plan, Hill hired — at his own expense — legendary roadbuilder Samuel Lancaster as engineer.

Soon, following the election of some road-friendly county commissioners, the project got a green light.

Lancaster scouted a route that threaded past waterfalls and scenic spots like the string in a pearl necklace. His highway would be specially oriented to frame picturesque vistas here and there, and would be carried over gulleys and across sheer cliff faces on picturesque concrete bridges and causeways. Everywhere possible, drop-offs would be protected by a rustic, stony guardrail, to stop cars from tumbling over the edge — made by the same Italian masons who built the foundation for the Vista House.

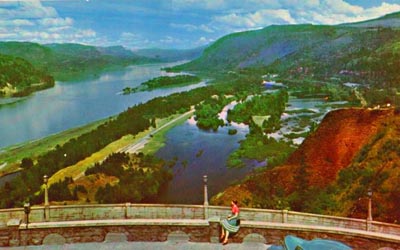

This 1930s-era postcard shows the view looking east from the parapet

of the Vista House. [Bigger image: 1200px]

Wealthy swells get behind the plan

Portland swells bought up property along the way — waterfalls, stony outcroppings, picturesque viewpoints — to serve as parks. Of course, they bought up some for themselves, too.

Portland’s elite helped in other ways, too. C. Lester Horn tells of one recalcitrant landowner (whom he is careful not to identify by name) who’d vowed to fight condemnation proceedings, to keep this highway from coming through his land. The landowner was a Portland businessman, and one of his major customers was the Benson Hotel, then the nicest in Portland. Simon Benson, when he heard, called him on the telephone personally: Could he please send a messenger over to pick up an urgent letter?

This postcard shows the old salmon cannery that used to stand at the

foot of the bluff, back when the Columbia had a commercially viable

salmon run. [Bigger image: 1200px]

The landowner could, of course. But when the messenger returned, the letter he brought was a cancellation of all business from the Benson Hotel. So he, in turn, got on the phone to Benson: Could Benson please send a bellhop over to pick up an urgent reply?

Benson could, of course, and when the bellhop returned, what he brought was a signed and notarized easement allowing the highway to pass through the property.

Benson also famously paid for the footbridge that crosses near the bottom of Multnomah Falls. While chatting with Lancaster, the engineer, about how nice it would be to have a bridge there, Benson asked casually what it might cost to do so. When Lancaster came up with a figure, Benson came up with a checkbook, and there, on the spot, paid for it.

Successful — all too successful

In the end, Lancaster’s road came to be far more successful than he and Hill ever dreamed. In fact, it quickly became a victim of that success, as it grew choked with heavy commercial traffic that caused noticeable deterioration.

Here is an image of Multnomah Falls Lodge in the mid-1950s. The lodge

can still be reached from a surviving section of the old scenic highway;

there's also a pedestrian tunnel that brings visitors over from the nearby

freeway. [Larger image: 1800 x 1136 px]

By then, the aesthetic qualities that had motivated the Portland aristocrats to finance the road so generously were mostly gone from American roadbuilding. People just wanted to get somewhere fast, not dawdle along an unnecessarily long detour and gawk at the same waterfall they had passed every day for five years on the way to work.

So starting in the late 1930s, newer and more bland roadways, mostly running along the river near water level, started replacing segments of the road. Finally, with the construction of Interstate 84 in the early 1960s, the highway was fully freed to return to the use the Portland plutocrats originally envisioned — as the string in a scenic pearl necklace.

And yes, except for occasional closures for remodeling and maintenance, the Crown Point Vista House rest area has been in service the entire time.

(Sources: Lancaster, Samuel. The Columbia: America’s Great Highway …. Portland: Kilham, 1916; Horn, C. Lester. “Oregon’s Columbia River Highway,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, Sept. 1965; www.columbiariverhighway.com; https://vistahouse.com)

TAGS: #ColumbiaRiverHighway #SamuelHill #SimonBenson #LesterHorn #MultnomahFalls #GoodRoads #CrownPointVistaHouse #Gorge #Corbett #SamuelLancaster