Mountain town of Bourne was home of a magnificent swindle

Though home to some productive mines, the Blue Mountain boomtown made much of its money working the suckers back east; then its head honcho disappeared into the night with the money, hours ahead of the law.

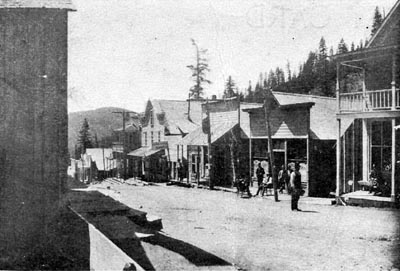

A photo of downtown Bourne, Oregon, during the boom years of hard-

rock gold mining and swindling the suckers back east

, circa 1905.

(Photo: Baker County Library, Baker City)

By Finn J.D. John — November 1, 2010

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

When it comes to attracting swindlers and charlatans, there’s nothing quite as effective as gold.

And nowhere in Oregon was that fact more clear than in the bustling boomtown of Bourne — what today is a tiny ghost town, seven miles out of Sumpter along the banks of Cracker Creek.

Bourne, Oregon, was the home of several thousand people, along with a large collection of promising-looking but relatively unproductive mines, a palatial residence and a printing press that, in Miles F. Potter’s words, “hardly had an opportunity to cool off for six years.” Its glory days ran from 1900 to 1906, when the mastermind of its multi-million-dollar municipal swindle skipped town just hours ahead of the law.

Here’s the story:

Gold-mining fortunes being made — and invested

In the late 1800s, miners started discovering massive veins of gold in the rugged, remote regions of Oregon’s Blue Mountains.

The town of Bourne as it appeared in 1921, looking out from the front

porch of the White mansion.

(Photo: Baker County Library, Baker City)

In short order, towns like Granite and Sumpter sprang up from the rocks, mining companies started setting up shop and representatives of a species of rugged, hard-drinking, hard-punching men drifted into the region to work the mines.

By this time, technological breakthroughs had made it possible to get a lot more gold out of a promising vein than the hopeful prospectors of 1849 had been able to, but it cost a lot of money to do it. That meant mines were more valuable to big industrial mining concerns than to individual prospectors. And with the fortunes that were being cracked out of the earth at the time, big industrial mining concerns were springing up on stock exchanges all over the world. Financiers in London were buying, sight unseen, mines in places like Copperfield, Oregon. And they were doing really well.

Mining gold, or milking suckers?

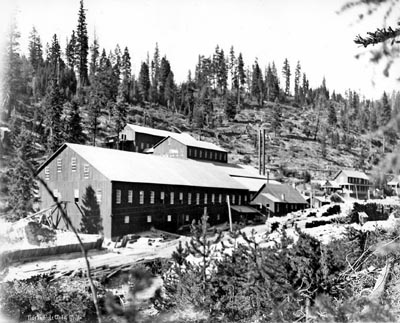

The North Pole Mine and stamp mill as it looked during the boom years.

The stamp mill, below Bourne, was a mile and a half from the mine,

connected by a tramway of 7/8 inch cable with 200 buckets of 250-

pound capacity.

The North Pole was a very successful mine, but by the

time Wallace White arrived, its best years were behind it.

(Photo: Baker County Library, Baker City)

It was probably inevitable that someone in the mining district would figure out, sooner or later, how to work this system to mine a different resource: not gold from the ground, but “investments” from suckers. It was simple supply and demand: There was a market for mining-opportunity fantasies. And into that market stepped F. Wallace White.

White worked the system like the pro he was. First, he hauled a printing press up Cracker Creek to the little boomtown of Bourne, which was at the time a fading sister city to nearby Granite and Sumpter. A few hundred miners lived there and worked nearby mines, but those mines were playing out and the freelance miners weren’t having as much luck as their colleagues in the other towns.

For White, it was the perfect opportunity. After all, he wasn't in the market for mines that actually produced; why pay extra for something you don't need?

A license to print money

Soon his printing press was in motion. Its main purpose was to crank out two newspapers. One, for local consumption, served as a typical small-town weekly paper and was more or less truthful.

Local resident Lee Robertson at upper level entrance to

the North Pole Mine, located less than a mile north of

Bourne, probably sometime in the 1920s.

(Photo: Baker County Library, Baker City)

The other, distributed nationally wherever suckers might congregate, contained almost nothing but lies — a gold-mining fantasy that would have been worthy of Walt Disney himself — had Walt been a swindler, that is. It was designed to look exactly like a real, honest small-town weekly newspaper, kind of like Main Street U.S.A. at Disneyland was designed to look like a real, honest small-town main street.

This publication spun fantastic but convincing tales of mammoth gold strikes, of huge capital construction projects, of rich shipments of bullion. And, of course, it offered readers opportunities to buy into this fairyland investment opportunity.

A song and dance for visiting suckers

With a $7.5 million stock offering, White launched The Sampson Company Limited, with offices in London, New York City and Bourne. He bought up the playing-out mines in the Cracker Creek area. When investors came to visit, he put on a dazzling show for them at his rustic-but-lovely terraced mansion with its formal dining room and ballroom, and at the mouths of promising-looking mines guarded by burly men with steel in their eyes and shotguns in their hands.

And the money poured in.

Eventually investors started getting wise ...

Meanwhile, other shysters were working the suckers too, and the marks were starting to get a little smarter — or perhaps it was just that so many people had been ripped off that they couldn’t fool themselves any more.

F. Wallace White’s mansion in Bourne as it looked in 1928. This photo

was taken 22 years after White, having swindled millions of dollars

from investors in phony gold mines, skipped town in the middle of the

night just a few steps ahead of federal investigators.

(Photo: Baker County Library, Baker City)

In fact, the legitimate mine financing industry was having trouble raising capital too, because so many investors simply thought any gold mine was crooked. The governor of Pennsylvania actually threatened to outlaw the sale of any Oregon mining stock in his state.

In response, the scammers spent ever more money. Full-page newspaper ads started appearing: “You can enter the temple of fortune by purchasing HIAWATHA MINING STOCK,” screamed one. (There is no record of the Hiawatha having ever produced anything.) “Buy CONSOLIDATED STANDARD … Dividends are sure to follow as day succeeds night. $500,000 worth of rich ore waiting to be processed,” promised another. (Consolidated Standard produced only a tiny trickle of gold.)

Police were getting wiser, too

But as for White, by 1906 he was starting to get nervous. What he was doing with his printing press constituted mail fraud, and in his six rich and productive years of mining far-distant suckers he’d made himself a small army of enemies, many of whom had friends in important places.

Finding Bourne, Ore., today can be a challenge.

(View a larger map)

So one night, White simply disappeared from Bourne. He left everything behind but the money. Authorities did finally catch up with him, many years later, still diligently operating mail-fraud swindles and no doubt muttering to himself that after this next big score, he was going to quit for real this time.

As for Bourne, the town melted away. There wasn’t enough gold to keep the place busy. Most of the miners went downstream to Sumpter or across the ridge to Granite, or out of the hills to Baker City. A few families remained. Today, though, it’s empty, and not coming back — it’s part of a national forest.

(Sources: Potter, Miles F. Oregon’s Golden Years: Bonanza of the West. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton, 1982; Holbrook, Stewart. The Far Corner. Sausalito, Calif.: Comstock, 1976)

TAGS: #Bourne #SaltedGoldMines #CrackerCreek #Suckers #MilesPotter #Sumpter #WallaceWhite #Granite #SampsonCompany #HiawathaMine #ConsolidatedStandardMine #StewartHolbrook