Oregon City is home of America's steepest street

You can't drive on it, though, or even walk — the only way to use this officially platted city street is by riding America's one and only municipal elevator.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2024 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

By Finn J.D. John — October 10, 2010

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

In the record books, you’ll find a street in Pittsburgh listed as the steepest in the U.S. It slopes upward at 18.5 degrees, which is a 35 percent grade.

Well, the record books are wrong. Because the steepest street in the U.S., and indeed the world, is Elevator Street in Oregon City, with a grade of – uh, 90 degrees.

(It may share the honor with some other vertical streets, but it's an ironclad guarantee that no street in the world is steeper; the laws of physics are funny that way.)

Elevator Street is officially mapped and platted and is 130 feet long. It runs straight up the side of a cliff. And during the height of the tourist season, as many as 1,300 people use it every day.

To do that, they have to ride the only municipal elevator in the country.

Why Oregon City needed an elevator

This postcard image, dating from shortly after the Oregon City bridge

was built in 1924, shows the old elevator towering like a grain silo

over the city. The open-scaffold structure extending from the top of the

elevator to the right side of the picture is the catwalk, on which riders

had to cross 90 feet above the railroad tracks — which must have been

tough of people with vertigo.

Here’s the story of how that elevator came to be: In the mid-1800s, Oregon City was originally settled on a narrow shelf of land just downstream from Willamette Falls. On the west was the river, smooth and lazy and very deep after its mad rush down the falls, oozing toward Portland and the sea. On the east, just a few dozen yards away, was a sheer rock wall, about 100 feet high.

Well, it wasn’t long before the settlement got too big for that shelf above the river, and people started settling at the top of the bluff. That was fine, as long as a person was OK with taking a long, steep, slippery pathway down and back up again every time he or she wanted to come to the business district. Later on, sets of stairs were built to make things easier, and one guesses they did; but at more than 700 steps, they were quite literally not for the faint of heart. One could go around the cliffs to the south, but that involved hitching up the buggy.

It was a problem.

"Not in MY back yard, you don't!"

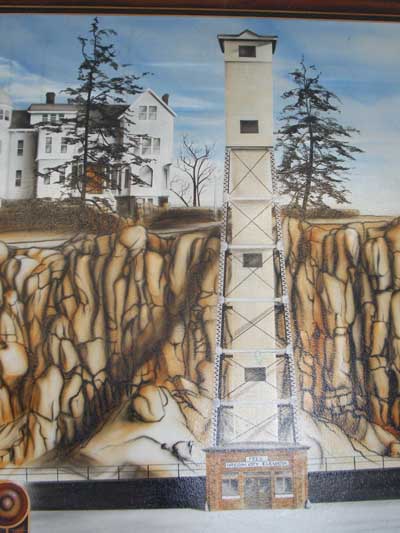

This mural depicting the old elevator appears in the viewing area at the

top of the current elevator.

By 1912 it was a major problem, and the city decided to do something about it. It presented the residents with a ballot measure to build an elevator at the bluff; this was shot down at first, but passed six months later.

Then the trouble really started. Most everyone agreed the city needed an elevator somewhere, but most everyone also thought it should not be near his or her house. And by this time, wealthy families had staked out the prime real estate on the top of the bluffs, with a gorgeous view of the city, high enough above the railroad tracks not to be too noisy. These folks were especially adamant: “You’re not ruining MY view with that thing!” Finally the city had to force the issue, through the Oregon Supreme Court.

The creaky, scary, water-powered solution ...

In late 1915, the elevator was ready to go. It was a big steel-and-wood affair and was actually powered by water pressure supplied by the municipal water system. It took 200,000 gallons to move the elevator from the bottom to the top; every time the elevator started up the shaft, water pressure in the surrounding houses would drop substantially. Also, it took the elevator as much as four swaying, jerky minutes to crawl up the bluff — that’s four to six inches per second, about a third as fast as a guy climbing a ladder. At the top, there was a 35-foot catwalk to cross, 90 feet above the railroad tracks, before the traveler was back on solid ground.

... It sometimes stopped halfway up

Nor was the thing particularly reliable. For those days when the elevator decided to stop moving halfway up, there was a handy trap door for folks to climb out of, and a narrow ladder that would take passengers down to safety.

This hand-tinted postcard image dates from within a few years of the

turn of the 20th century. It shows the part of Oregon City closest to the

falls. [Larger image: 1200 px wide]

Despite these drawbacks, Oregon City was very proud of the thing. On its opening day, pretty much the whole city — population, at the time, just under 4,000 people — came out to take a ride.

Electricity brings a big improvement

Still, it didn’t really become popular until 1924, when the city electrified it. This brought the commute time from bottom to top down to 30 seconds, and they were much less dramatic seconds at that.

The modern elevator is built

The elevator you see in Oregon City today was designed in 1954. The old one was starting to break down too much, and ridership was dropping fast. Seeking something cheap, the city specified something plain and unadorned, but clearly they also wanted it to be sleek and modern. The low bid came in at $116,000, and the next year the new structure was unveiled. It’s staffed with an elevator operator, and takes 15 seconds to cover the distance from bottom to top. And yes, it’s still free to ride.

As far as I’ve been able to learn no one has ever gotten stuck in it. But for those who don’t want to take any chances, there’s a nice set of permanent cement stairs leading up the bluff next to the elevator. There are 197 of them. This is a big improvement on the 700 or so that the pioneers had to deal with, going up and down around obstacles, but it’s still a lot.

(Sources: www.orcity.org; Friedman, Ralph. In Search of Western Oregon. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton, 1990; Hart, Deanna. “Going to the Next Level,” American City and County magazine, June 2008.)

TAGS: #ElevatorStreet #MunicipalElevator #SingerHill #NIMBY #WaterPowered #RalphFriedman #DeannaHart