How Oregon almost became part of Canada, eh?

Few people know how close Oregon came to officially becoming a British possession under the treaty that ended the War of 1812 — and the thing that "saved" the state was an expedition everyone thinks of as a disastrous failure.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2025 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

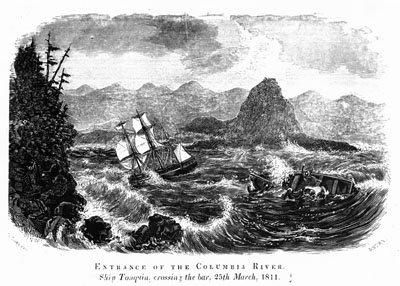

This old engraving, signed "Avery," shows what everyone assumes

was

the fate of the landing parties sent ashore across the Columbia

River Bar

in a rowboat at Capt. Jonathan Thorn's insistence.

(Image: Oregon

Historical Society) [Larger image: 1200 x 858 px]

By Finn J.D. John — August 8, 2010

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

THE STORY OF John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company expedition to Oregon in 1810 is remembered today — if it's remembered at all — as a dismal failure. Dozens of people died, his ship sank and he ended up selling Fort Astoria to the British at a severe loss.

But what most people don’t know is that if Astor's explorers had stayed home, the Oregon Territory would probably be a Canadian province today.

Here's the story:

The Astor expedition left shortly after Lewis and Clark got back. It involved two journeys, one by land and one by sea, to the mouth of the Columbia to set up a network of trading posts there.

Arrogant captain's loud lips sink his ship

The project was ill-starred from the start. The ship Astor sent around the horn, the 94-foot three-masted windjammer Tonquin, was captained by a tactless, arrogant ex-Navy officer named Jonathan Thorn. Thorn, when he got to Astoria, insisted on sending a rowboat out to scout the channel immediately despite the heavy seas. The first boat was never heard from again; the second was almost lost; and a third located the channel for the Tonquin, but swamped and sank before it could get back to the ship.

So the Tonquin sailed into Baker Bay and founded what's now Astoria. Then it put back out to sea and headed north, making for the Russian colony of Sitka.

It never made it. Thorn's personal style infuriated not only his passengers, but also the natives who came to trade with him. This last item proved fatal when, during trading on Vancouver Island, he had the local tribal chief thrown overboard, apparently thinking the soaking would get him to lower his asking price for pelts. The next morning, the natives were back, and told Thorn they’d learned their lesson and were now ready to deal. Once on board, they got out knives and proceeded to avenge the insult to their chief. The next day, someone touched off the powder magazine, and that was the end of the Tonquin, most of its crew and a great many natives as well.

But by then the damage had been done. Thorn’s bargaining style had not only cost the expedition its ship and left the surviving Astorians stranded in the wilderness, it had angered natives all along the coast. The people the Tonquin had left to found Fort Astoria, on the northwest tip of what’s now Oregon, had a lot of fences to mend, and many of the natives clearly didn’t plan to leave them alive long enough to mend them. In desperation, Pacific Fur Company partner Duncan McDougal pretended to have a “bottle of smallpox,” which he would uncork if attacked. This kept them alive, but made them even more friendless.

Arrogant rivermen strand their expedition

Meanwhile, Astor's overland expedition was working its way Westward more or less along what would become the Oregon Trail years later. The overland party fared a little better than the seafarers, in no small part because of the presence of Marie Dorion and her family. Things went relatively well for them at first. But about halfway through its journey, the overland party, like Capt. Thorn's argonauts, fell victim to arrogance.

This time it was the French voyageurs in the party. Overconfident in their skills as river navigators, they convinced the rest of the team that they should give up their horses and take to the river — Henry’s Fork, which drains into the Snake.

Anyone familiar with the Snake River’s reputation for navigability can guess what happened next: They found themselves stranded, in the middle of the Snake River Desert in what’s now southern Idaho, next to an utterly non-navigable river.

Most of the overland crew managed to get through, one way or another. But they only beat a rival British expedition by a few months, and they utterly failed to establish a credible land route. With the Tonquin gone, the British in control of the high seas and the War of 1812 breaking out, Astor gave up and sold out to the British.

British seize British property by accident

A month after the sale was completed, a British warship arrived and “seized” the newly purchased Fort Astoria. When told that he was seizing British property, the captain replied that his orders were to seize the fort and an order was an order.

A claim on the Northwest

Now comes the interesting part. When the war ended, part of the negotiations centered around the Oregon territory, and who would get to claim it. Feeble and isolated as it was, Fort Astoria was American when the war broke out; it wasn’t sold until after hostilities broke out.

Moreover, the fort had been seized by military force — although not from the Americans — so that made it, technically, a spoil of war. The war-ending treaty involved returning all spoils of war. So the Astorians, briefly, got it back, although they immediately returned it to the people they’d sold it to.

U.S., Britian agree to "share"

The important result of all this was that when the peace treaty negotiations got under way, both America and Britain had a credible presence in, and therefore a claim on, the Oregon territory.

So when their status was made official by the resulting treaty, the first of several joint-occupancy arrangements was made.

Joint occupancy is what led, under the pressure of thousands of American homesteaders in the subsequent decades, to Oregon and Washington becoming part of the U.S. rather than Canada.

But if the Astorians had not been in Oregon when the war broke out, or had sold their holdings to the British before the war got started, the treaty that ended the war would almost certainly have defined the U.S-British border and made Britain’s claims on Oregon official.

And we’d all be speaking Canadian today, eh?

(Sources: O.Ned Eddins’ historical Website, www.thefurtrapper.com; Gulick, Bill. Roadside History of Oregon. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press, 1991; Kaza, Roger. Podcast episode 2411, Engines of our Ingenuity. Houston: KUHF Radio, 2008; www.oregonencyclopedia.org)

TAGS: #Tonquin #Shipwreck #WarOf1812 #JointOccupancyTreaty #England #PacificFurCompany #JohnJacobAstor #FortClatsop #FortAstoria #OregonTerritory #JonathanThorn #54-40 #LewisAndClark #BakerBay #MarieDorion #SnakeRiver #BillGulick #RogerKaza

-30-