In Mohawk Valley, local school issues got debated with dynamite

Last and most successful explosion, in 1909, was rumored to have been the work of students, who felt they needed a new building; others suspected to be work of a grumpy old pioneer and experienced "dynamite fisherman" who lived nearby.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2024 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

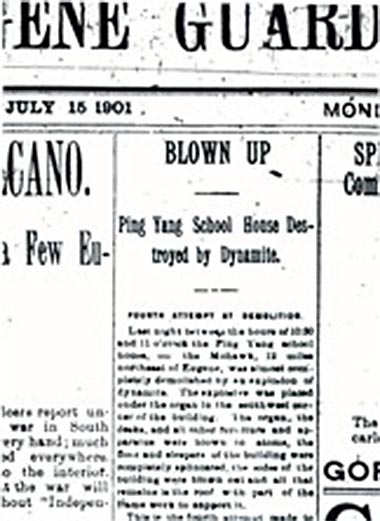

A clip from the Eugene Guard announcing the second attempt to

blow up Ping Yang School with dynamite. (Image: Steve Williamson's

page,

https://members.efn.org/~opal/pingyang.htm

By Finn J.D. John — March 14, 2010

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

Next time a debate over a capital levy for local schools gets ugly, count your blessings. Some Oregonians used to argue over this sort of thing with sticks of dynamite.

Back in 1895, a little one-room schoolhouse was built in an unincorporated town that today is known as Mohawk. Over the years it’s also been called Donna and Ping Yang – Ping Yang having been, at the time, the popular English pronunciation of Pyongyang, then the capital of Korea (and today the capital of North Korea). Pyongyang had just made headlines as the scene of a historic battle between the colonial forces of China, which had dominated Korea for centuries, and the “liberating” armies of Japan (click here to see a New York Times article from Sept. 18, 1894); this fight had captured the imagination of many Oregonians, and was a regular subject in the pulps and serials of the day.

Battlefield School

There are other theories on the origin of the name. But if the Ping Yang School was in fact named after a distant battlefield, it was an appropriate choice, because it quickly became one – in more than just a metaphorical sense. You see, a sizeable percentage of the community did not want the school built where it ended up.

Matches, coal oil and dynamite

Almost immediately after it was built, someone tried to torch the school by dumping coal oil on the floor inside and lighting it off. This did not work – probably because it was late winter at the time. Anyone who’s tried to fire up a burn pile on a typical Willamette Valley February day will not be surprised at this.

Three months later, though, a more successful attempt was made, involving dynamite. This seems to have established a tradition at Ping Yang. Over the following 15 years, three more attempts were made to blow the building up, with increasing success, until in 1909 the school had to be replaced with a bigger structure – which served the community uneventfully until it was replaced in 1963 with Mohawk Elementary School, just a few hundred yards away on the other side of Marcola Road.

So, why all the fireworks?

Can't stop progress — or can you?

Steve Williamson suggests it was a land-use issue. The Mohawk Valley is prime timber country. The valley floor is nice and flat; the surrounding hills are gentle, well-watered and thick with trees. Soon there was a railroad heading up the valley, carrying logs down to the mill and timber workers and their families up to live. Some of the older Mohawk Valley residents, who’d been there since before Oregon statehood, saw their wild hideaway turning into an industrial community, complete with roaring machinery, howling steam whistles and screeching buzz-saw blades. One of these, “Old Joe” Huddleston, was particularly disgusted after the railroad cut up the valley right next to his property.

Blatant racism

To make things more complicated, Old Joe was a hard-core racist, and he was singing that song nice and loud when the school was bombed for the third time, in 1900. This blast took out most of the walls and left just a roof supported on a few surviving bits of framing. At that time, Huddleston was campaigning fiercely against the school, which – like the railroad – was annoyingly close to his home. He was using a racist, xenophobic appeal centered around opposition to the presence of Chinese and Japanese people then working on railroads and other back-breaking projects around the country. The Ping Yang School likely had never had a Chinese or Japanese student even walking into the building; there were no East Asian families in that part of the Mohawk Valley at the time (editor's note: Please see note at bottom of page). But it had a Korean-sounding name, and Japanese workers on the railroad line had become a familiar sight.

So when the school blew up, Huddleston was widely viewed as the No. 1 suspect – especially since he was known to be an experienced “dynamite fisherman” on area waterways.

No charges ever filed

Old Joe was never charged. No one else was either, for that matter. But after Old Joe moved out of the valley a couple years later, the explosions stopped – well, mostly. In or shortly before 1909, there was one more, and this one finished off the building.

"Mom, me an' Wally blew up the school!"

According to a student attending the school at the time, a group of pupils decided they needed a better building, and that the way to get one was – well, what had become the traditional Mohawk Valley way: Dynamite.

They got their new school. It lasted until 1963, when it was taken out of service in a far less dramatic fashion – with a school-board vote – and replaced with Mohawk Elementary.

(Sources: Lane County Historical Museum exhibit; Eugene Register-Guard, 6-7-63; Eugene Guard 7-15-01; Williamson, Stephen. The Ping Yang School Bombing, https://www.efn.org/~opal/pingyang.htm)

NOTE: The original version of this story stated that there were no East Asian families in the Mohawk Valley at this time, a statement that I am pretty sure was incorrect. There was a Japanese community at Mabel, about 20 miles upriver, during at least some of the time discussed in this article. I have updated the story to reflect this. (Thanks, Mitch, for pointing this out.) By the way, if you're interested in more about the Japanese colony, Stephen Williamson has studied that extensively as well: https://www.efn.org/~opal/coastrange.htm

-30-