Underground city found in Pendleton potholes

Tunnels contained entire businesses and storefronts, once used by Chinese residents, brothel girls, and local merchants to avoid contact with liquored-up cowboys; today they are a popular tourist attraction for the city.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2024 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

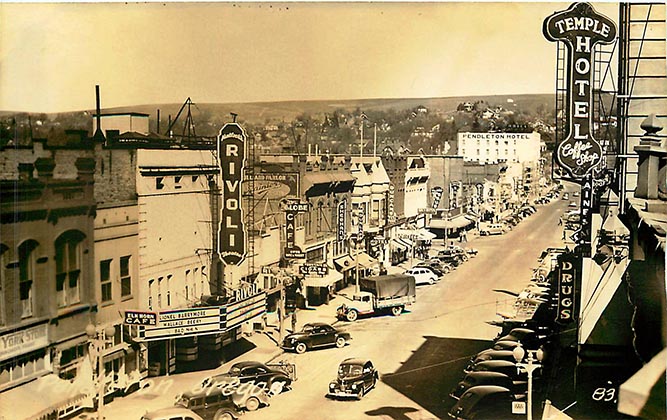

A postcard image of downtown Pendleton in the early 1940s. When this

image was made, few if any residents had any idea there was a long-

abandoned underground city beneath these streets.

By Finn J.D. John — January 31, 2010

Extensively revised on October 29, 2024

Downloadable audio file (MP3)

not currently available

Pendleton had always had potholes. Big, intractible ones that seemed to be unfillable.

Pendleton also had always had rumors of underground tunnels. Supposedly the Chinese railroad workers had dug them back in the 1800s. Nearly everybody knew somebody who knew somebody who had found one leading off a basement behind a furnace, but had since been walled off or filled up with gravel.

It wasn't until around 1980, though, that Pendleton residents figured out these two things were related. When the really pothole-prone roadbeds were excavated to be rebuilt, workers found the under-road tunnels had been causing the potholes.

And those tunnels — they were way more extensive than folks had realized. They almost amounted to an underground city — complete with businesses both legal and illegal — in the basements of downtown buildings, all connected by tunnels.

For several decades around the turn of the 20th century, there were two towns in Pendleton: One above the soil line for all to see, and one below it known only to the chosen few.

The underground town got its start in the mid-1800s, but really got going in the 1880s. At that time, the hard work of building the railroads was mostly finished — the transcontinental railroad linked Portland to the East Coast in 1883. So the country no longer needed the thousands of Chinese workers who had helped build them. They had gone from providing a valuable service to a new nation, to competing with “native sons” for jobs and depressing the wages.

The Pendleton fairgrounds, all decked out for the Pendleton Round-Up, in

the 1920s or 1930s. Note the Indian village in the foreground.

The climate in the U.S., never warm and friendly for them, was becoming downright hostile. Crimes against Chinese people were not prosecuted. The Chinese Exclusion Act and other laws like it were promulgated, prohibiting them from becoming citizens or owning land and blocking further immigration. Residents of West Coast cities such as Tacoma and Sacramento started forming mobs and running them out of town. It wasn’t a full-blown pogrom, but it could easily have become one at any time — and only an idiot would just sit back and wait for that to happen.

The Chinese in America were not idiots. In various cities, they responded to this official and unofficial persecution by forming self-sufficient ghettos — Chinatowns — and keeping such a low profile that today, the official estimate of how many Chinese there were in Oregon — 150,000 — is nothing but a wild guess. No one really knows.

In Pendleton, the Chinese had an additional challenge: Cowboys. They tended to get liquored up and commit crimes after sunset. Chinese people made very appealing victims for this — one could do all sorts of things to them, up to and including murder in many circumstances, without much fear of punishment — and they were easily identifiable. It soon became an unofficial rule that Chinese people must be off the streets by sundown. (In some places in Oregon, that rule actually was made official.)

So, to facilitate after-dark movement from one Chinese-owned business to another, access tunnels were dug. And added on to. And expanded.

Meanwhile, other downtown business owners and residents who didn't care to venture out on the wild and frolicksome cowboy-infested streets of downtown after dark were doing the same thing, for the same reason. This was especially important for the "goodtime girls" of Pendleton's downtown bordellos. If a working girl needed something after dark, or just wanted an ice cream soda, she pretty much couldn't leave the building without risking sexual assault or worse. So, she'd go down to the basement, cross the street to the basement of McCardy's Ice Cream Shop, and buy her soda at their basement cash register.

The tunnels became very useful for illegal businesses such as opium dens and, after Oregon instituted Prohibition in 1915, speakeasies, which were set up in basements with a concealed entrance to the tunnels through which personnel might flee in the event of a police raid — not that that happened much; Pendleton was famously lax when it came to Prohibition enforcement.

After the Volstead Act kicked off nationwide Prohibition in 1919, tunnels became even more useful for this — especially the tunnel that led to the airport.

Yet the tunnels remained, for the most part, a secret — until those potholes started to appear.

Today, you can take a tour of these tunnels, guided by an actual historian. It includes both legal and illegal businesses operated entirely underground — opium dens, laundries, apothecary shops, everything a working girl or Chinese laborer might need after dark in a hostile, foreign land.

(Sources: Gulick, Bill. Roadside History of Oregon. Missoula: Mountain Press, 1991; www.chineseamericanheroes.org; www.pendletonundergroundtours.org)

TAGS: #PendletonUnderground #ChineseExclusionAct #Cowboys #SundownLaws #Potholes #TranscontinentalRailroad #Chinatown #OpiumDens #Prohibition #Apothecary #BillGulick

-30-