Biggest meteorite ever found in U.S. came from West Linn, Ore.

Massive 16-ton chunk of iron was found by a neighboring property owner, who dragged it half a mile in an attempt to steal it; today it's in the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

EDITOR'S NOTE: A revised, updated and expanded version of this story was published in 2018 and is recommended in preference to this older one. To read it, click here.

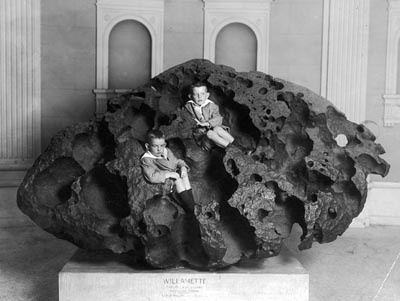

Two small boys clown around in the holes of the 16-ton Willamette

Meteorite, where it sits on display in the Americvan Museum of

Natural History in New York in 1911.

By Finn J.D. John — January 18, 2010

The old playground doctrine of “finders keepers” does not apply to meteorites. At least, that’s what the Oregon Supreme Court said in 1905, when deciding who got to keep the Willamette Meteorite – the largest meteorite ever found in the United States, before or since.

Here’s the story: Ellis Hughes, a settler in the West Linn area, near the Tualatin River, was out prospecting for minerals with a friend in 1902. Hughes bounced his rock hammer off a projecting piece in the forest and got a metallic “ting” instead of a rocky “chup.”

Well, the two were really excited at first. They figured this was a “reef” sticking out of the top of a massive vein of iron that could make them both very wealthy. But they soon made two sobering discoveries: First, it was an isolated block. And second, it wasn’t on Hughes’ property. They’d strayed over onto the neighboring plot, owned by – ironically, given that the meteorite was more than 90 percent iron – the Oregon Iron and Steel Company.

Hughes kept mum and tried to buy the land. Nothing doing. So he, his wife and his 15-year-old stepson toiled for a solid three months at dragging the 32,000-pound mass across three-quarters of a mile of forest floor and onto Hughes’ property. This done, he announced his find, built a shed over it and started charging admission to see it.

Two unidentified people -- most likely Ellis Hughes and his stepson --

pose with the Willamette Meteorite in 1905. The meteorite has been

loaded onto a crude wooden cart so that it could be hauled through

the woods onto Ellis's property.

I haven’t been able to learn how the Oregon Iron and Steel Company found out the meteorite had been moved. Probably Hughes’ attempts to buy the land aroused some suspicion and prompted company officials to investigate. In any case, figure it out they did, and filed a lawsuit demanding that Hughes give it back.

Which he did. But not before fighting it all the way up to the Oregon Supreme Court, in late 1905 – just in time for Oregon Iron and Steel to haul it up to Portland for the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition, at which it was displayed proudly and drew much notice. Afterward, it was purchased by Sarah Dodge and donated to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City – where it remains to this day.

The meteorite apparently fell on a glacier during the last ice age. During the Missoula Floods, the ice in which it was embedded formed an iceberg and roared down the Columbia River Gorge, eddying back up into the Willamette Valley and finally being deposited on top of the sediment when the ice melted away.

It’s composed of 91.65 percent iron, 7.88 percent nickel, 0.21 percent cobalt and 0.09 percent phosphorous.

In Oregon, there are two replicas of the meteorite on display: one at the United Methodist Church in West Linn, near where it was found; the other outside the University of Oregon’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History in Eugene.

The local Native American tribes had treasured the meteorite, calling it “tomonowos” – “visitor from the moon.” In 1990, they sued for its return. But they came to an agreement with the museum in 2000 that let them come visit the meteorite in New York and hold private ceremonies around it; the deal also says if the museum ever takes it off permanent display, the tribes will get it back.

A member of the state House of Representatives weighed in seven years later by introducing a bill that would demand its return to the state of Oregon. The tribes said no one had talked to them about it, but they were happy with the arrangement they’d made and did not support the new bill. So, as Willamette Week put it in an editorial that year, “neither the bill nor the 16-ton meteorite went anywhere.”

(Sources: American Museum Journal, Vol. 6 (1906); Seigneur, Cordelia Becker. Images of America: West Linn. Mount Pleasant, S.C.: Arcadia, 2009; Oregon House Joint Resolution 30 (2007); www.absoluteastronomy.com)

-30-